Performance reporting – why is it important?

From ancient times, owners of resources have paid others to manage them. The manager’s goal was to maximise the return on the owner’s investment by making these resources perform as well as possible. To earn their boss’ trust, so they would be granted the freedom to manage these resources effectively, managers agreed to give an account of their activities. Sometimes, owners needed an extra layer of trust. That is, they wanted to be reassured that the manager’s account of activities could be relied on.

From ancient times, owners of resources have paid others to manage them. The manager’s goal was to maximise the return on the owner’s investment by making these resources perform as well as possible. To earn their boss’ trust, so they would be granted the freedom to manage these resources effectively, managers agreed to give an account of their activities. Sometimes, owners needed an extra layer of trust. That is, they wanted to be reassured that the manager’s account of activities could be relied on.

Henry I of England had the right idea. When he set up the Exchequer, he had officers examine the accounts. The official “hearing” of the accounts was known as the “audit” (from the Latin audire – to hear).

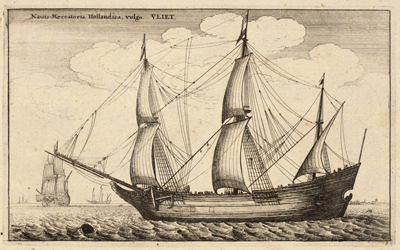

The separation of owner and manager – or investor and owner/manager – was a significant feature of commerce during the European renaissance and the Elizabethan period, when ships crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the New World for economic gain.

Ship captains needed to give an account to the rulers and merchants who financed them on how they’d spent the money and the riches gained as a result. If trust could not be established, no funding would be provided for the next journey. Merchants often used “auditors” to verify the riches.

The industrial revolution saw the emergence of large-scale factory production lines. The newly emerged middle-class investors wanted assurance that company directors and management could be trusted with their money. Company books needed to be kept and “balanced”. Again, the investors arranged for “auditors” to check the books for fraud and errors, with a particular eye on the company’s solvency – they wanted assurance that their investment was protected.

In the New Zealand public sector, the value of reporting publicly on financial and operational performance is essentially the same that accounting and reporting has had throughout the ages. It is all about the need for trust. So how can those who “own” the resources (that is, the citizens and taxpayers of New Zealand) be sure that those managing the resources (the government) are using them wisely and properly?

In the public sector, considerations go way beyond the desire for commercial return. Resources are used mainly to achieve societal objectives – therefore, performance reporting is arguably more important than financial reporting. Also, the separation of roles in public spending is far more complicated than in commercial life. These roles can include: the owner/“shareholder”, funder, purchaser, provider, and customer.

So how does the government earn the public’s trust in such a complicated arrangement? Well, it has to demonstrate that it is trustworthy by reporting accurately and transparently on its performance. Good performance reporting is closely linked to the qualities of good communication – it needs to be clear and understandable. For entities, a good starting point is to have a thoughtful description of how it organises and uses its resources to achieve its aims. Most importantly, good performance reporting will consider the end user’s needs – whether that user is a member of the public or a minister.

In the following video, Mike Scott (Assistant Auditor-General, Performance Audit Group), Marcus Jackson (Director, Research and Development), and I expand further on the importance of performance reporting. We explain why good quality performance reporting is essential in our modern democracy.

The financial assets report that Marcus mentions in the video is available on our website, as is as our recent report Reflections from our audits: Governance and accountability.