Part 4: Costs and funding of the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme

4.1

In this Part, we assess:

- the costs and funding of compensation to firearms owners;

- ACC's contribution to the scheme; and

- the costs and funding to administer the scheme.

4.2

We conclude that:

- the Police did not exceed the appropriation for the cost of compensation to date;

- ACC's decision to provide funds to the scheme is consistent with its functions and relied on reasonable actuarial assumptions that involved a high level of judgement; and

- the administrative costs of the scheme were higher than the Police's estimates, and the Police used a lot of their wider resources to support the scheme's administration.

4.3

We have assessed the efficiency and cost of the scheme's implementation according to the following four criteria:

- whether compensation and administrative costs were managed to budget;

- whether expenditure on compensation and administrative costs was appropriately authorised;

- whether expenditure on compensation and administration was well tracked and reported; and

- whether expenditure on compensation and administration was well managed to get value from the use of public funds.

Compensation costs did not exceed what was appropriated

4.4

The 2019 Budget included an appropriation of $150 million in Vote Police for compensation payments made as part of the scheme. This amount was based on the mid-range of estimates that the Police prepared. The known number of military-style semi-automatics and the estimated number of prohibited rifles and shotguns informed the Police's work.

4.5

The Police's 2018/19 annual report included a provision and associated expenditure of $150 million for compensating people handing in newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts. The estimated level of future costs was based on the best information available to the Police at the time.

4.6

The Police applied the following main assumptions in determining the cost of compensation:

- All newly prohibited firearms would be handed in.

- All of the roughly 15,000 military-style semi-automatic firearms are prohibited and would be handed in – this knowledge was based on the required record of ownership.

- Up to 20% of the estimated total 760,000 rifles and 2% of the estimated total 380,000 shotguns would be prohibited and handed in. These estimates were created using internal knowledge and discussions with trusted retailers.

- Pricing has been estimated based on discussions with trusted retailers and second-hand firearms data from the last three years.

4.7

As at 20 December 2019, the Police's provisional information reported that compensation costs were $102 million. The final compensation costs are currently unknown but will be higher because not all compensation for dealers has yet been processed.

4.8

At the end of February 2020, the Police were forecasting those costs to be about $120 million once they has completed remaining work for the scheme. This included the remaining payments yet to be made for unique prohibited items, dealer stock, gunsmith invoices for modifications, and dealer administration fees (the fees paid to dealers for being a collection channel).

ACC's contribution to the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme was compatible with its statutory functions

4.9

Within two days of the Christchurch attacks, the Treasury considered several potential sources of funding for a firearms buy-back scheme. These sources included ACC, existing or new budgets, a tax or duty, funds obtained back from criminals under proceeds of crime arrangements, or baseline savings.

4.10

The Treasury informed the Office of the Minister of Finance that, without changing legislation, ACC could contribute funding to the scheme under section 263 of the Accident Compensation Act 2001. Section 263 allows ACC to promote measures that reduce the incidence and severity of personal injury. Section 263(3) sets conditions for any ACC contribution to injury prevention measures, including that they are likely to result in a cost-effective reduction in actual or projected levy rates.

4.11

ACC carried out an actuarial assessment to assess whether it would be cost-effective for ACC to contribute to the scheme. This assessment concluded that, in the next 20 years, the benefits (the reduction in claim costs) will be about $70.5 million, or $1.76 for every $1 that ACC invested.

4.12

ACC's approach to assessing the funding contribution was consistent with its assessments of other funding decisions about injury prevention. ACC's injury prevention portfolio target for 2018/19, as described in its Service Agreement, was $1.80 of savings, on average, for every $1 invested.

4.13

The ACC Board made the decision to contribute funding of up to $40 million to the scheme. The decision to contribute funding was a resolution of the full Board, and the Board documented that decision through a written resolution, as required by the Crown Entities Act 2004.

4.14

The Chairperson of ACC wrote to the Minister for ACC on 4 April 2019 to offer funding support. The Minister accepted ACC's decision to contribute funding to the scheme and wrote to accept the offer on 14 June 2019. We understand that ACC determined that a contract was not needed in addition to the letter from the Minister accepting the ACC Board's offer of funding.

4.15

ACC's contribution was limited to funding compensation costs and the modification of newly prohibited firearms, and not the administrative costs of the scheme.

4.16

EY is also ACC's appointed auditor. We commissioned EY's actuary team to test ACC's actuarial assumptions behind the funding decision. EY concluded that, although the assumptions were based on a high degree of judgement, they appeared to be reasonable. The main uncertainty is that ACC's assessment of the extent of the reduction in claims might not be as expected.

4.17

To date, ACC has paid $20 million to the Police for the scheme. ACC told us that any further payment will depend on the final cost of the scheme. This is because ACC wishes to limit its contribution to 21.1% of the total firearms owners' compensation cost. This reflects the ACC Board's initial decision to contribute $40 million when it looked like the compensation cost could be about $190 million.

4.18

ACC will monitor firearms-related injuries and their effect on the Outstanding Claims Liability.

Administrative costs were higher than the Police's estimates

4.19

In March 2019, the Police produced an initial estimate of $18 million to fund the scheme's administrative costs. This amount was included as a new initiative in Budget 2019 as part of the General Crime Prevention Services appropriation.

4.20

The Police's estimate was completed quickly, before the costs of supporting technology were fully known. The estimate was based on a per-capita proportion of both the nationwide, and Australian Capital Territory's, costs of the Australian buy-back scheme. The Police took foreign exchange rates and inflation into account.

4.21

The Police now estimate that it will cost up to $35 million to administer the scheme. This includes the costs of staff time, contractors, and goods and services. This is nearly double the $18 million provided through the 2019 Budget for 2019/20 and includes about $5 million the Police spent in 2018/19 on the scheme's administration.

4.22

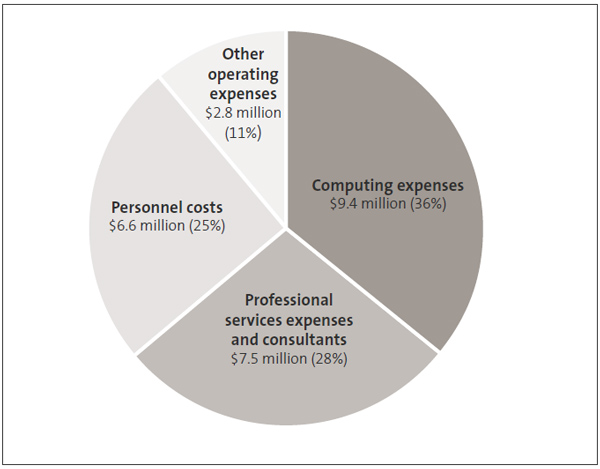

Figure 5 shows a high-level breakdown of the administrative costs at 31 December 2019. The total administrative cost at that date was slightly more than $26 million, with about two-thirds of the costs for computer services and for professional and consultancy services. One-quarter was for personnel costs (which exclude the personnel costs of police staff not engaged full time on the project).

Figure 5

Administrative costs of the scheme, by category, as at 31 December 2019

The administrative costs categories are divided into four segments. They are computing expenses ($9.4 million), professional services expenses and consultants ($7.5 million), personnel costs ($6.6 million), and other operating expenses ($2.8 million).

Source: Unaudited information from the New Zealand Police. Note: The numbers have been rounded to the nearest $100,000.

4.23

The Police have sought an increase to the $18 million provided for administrative costs in 2019/20, but decisions about that had not been finalised at the time of writing this report. If an increase is not approved, the Police will need to use resources from their General Crime Prevention Services appropriation to cover any administrative costs in excess of $18 million.

4.24

Authority to use those resources comes from the Police's general spending authority in the Crime Prevention appropriation (which can be used for any crime prevention activities). Doing so will affect other areas of the Police's work that could have been delivered with this funding.

4.25

Although the administrative costs of the scheme were considerably higher than what the Police estimated, there were adequate financial controls over administrative spending, including procurement. EY did not identify any material gaps in supplier management, purchasing, invoice processing, and payment processes. We did not see evidence of wasteful spending.

4.26

Administrative costs were not sufficiently covered in the original programme documentation. EY noted that police staff and contractors were investing significant time setting up and running the scheme, and it was likely that this time would have affected the Police's resources.

4.27

EY recommended that the Police report on the administrative and opportunity costs of the scheme. That information was not included in the Police's publicly reported dashboard information about the scheme's performance (see paragraph 2.20).

4.28

The Police's other resources also supported the scheme's implementation – for example, frontline staff working at local collection events. Using these resources to support the scheme meant that they were not available for other police work. This is an opportunity cost.

4.29

The Police do not separately record the time spent on the scheme by routinely rostered staff working less than full time on the scheme, so they cannot calculate this opportunity cost. This also means that the real cost of the scheme will be higher than the cost we have referred to in this report.