Part 3: Implementing the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme

3.1

In this Part, we assess:

- how well the local collection events were run;

- how the Police provided different ways for people to hand in their firearms, magazines, and parts;

- the Police's process for recruiting and training firearms assessors;

- the Police's communications plan and how it was implemented;

- how firearms, magazines, and parts were destroyed;

- the Police's systems and processes to implement the scheme; and

- the Police's information about the number of prohibited firearms and the implications of that information for implementing the scheme and assessing its performance.

3.2

We conclude that the Police implemented most aspects of the scheme effectively. However, the Police:

- could have communicated the complaints process better and made it more transparent; and

- could have introduced the option to modify firearms so they complied with the law sooner.

3.3

The number of firearms and parts collected or modified (61,332 as at 13 February 2020) was at the lower end of the range of the Police's estimates of the total number of newly prohibited firearms.

3.4

However, we are not able to form a conclusion on the level of compliance with the new regulatory regime because of the low confidence in, and wide range of, estimates of the total number of newly prohibited firearms in the community.

Local collection events were well run

3.5

Local collection events were the main way that people could hand in their newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts, either for compensation (buy-back) or under the amnesty. Typically, local collection events were held in community facilities such as community halls and stadiums.

3.6

The Police also provided the option to have firearms collected at people's homes in exceptional circumstances (for example, if they had large quantities of firearms or parts) or private collection events at gun clubs.

3.7

There were 605 local collection events. The first local collection event was held in Christchurch on the weekend of 13 and 14 July 2019. The final local collection events were held on 20 December 2019, the day the scheme ended. Local collection events took place throughout the country, including the Chatham Islands.

3.8

Planning and running each local collection event was a considerable logistical exercise and needed a significant amount of work. It involved setting up and running information communications technology (ICT) systems, and identifying and managing a range of risks, particularly to the health and safety of the public and police staff.

3.9

The Police used regional teams to manage the local collection events. For most events, an Inspector of Police led each local collection event, with a Senior Sergeant acting as second in command. Each team included police officers, assessors, administrative staff, and a telecommunications technician. Typically, at least 16 police staff and nine contractors were required to run a local collection event. These included:

- two armed police officers patrolling the car park and entrance to the building;

- a telecommunications technician;

- two people checking firearms for ammunition and making the firearms safe to continue through the local collection event;

- two or three assessment teams, each comprising an assessor, an administrator, and a person to photograph and label each item;

- a person transporting the firearms, magazines, and parts to a place for making them inoperative;

- a person operating a machine that bent the firearm in three places, making them inoperative;

- a concierge role to keep the public participating in the event engaged and informed or to answer questions from the public;

- an armed police officer overseeing security at the facility where the event was being held; and

- staff involved in off-site back-up security arrangements.

3.10

In the days leading up to each local collection event, the Police's Major Operations Centre provided real-time intelligence about risks in the area so the Police could put in place mitigation steps, where required.

The Police were empathetic to firearms owners

3.11

Many people have emotional and financial attachments to their firearms – for example, firearms that have been handed down from generation to generation. Giving up a legally obtained item that had been previously used lawfully was also distressing for some people.

3.12

Police staff, assessors, and other support staff understood this and showed empathy towards people handing in their firearms. Senior police staff were present at most of the local collection events. They engaged with firearms owners and their families at those events and stressed to them that handing in their firearms, magazines, and parts was the right thing to do.

People attending local collection events were positive about how the events were managed

3.13

The Police commissioned a research company to carry out face-to-face interviews at local collection events between 31 August and 30 September 2019. Overall, there were 438 interviews at 19 local collection events. Respondents were largely positive about their experiences at local collection events (see Figure 2). The interviews identified that the Police could improve two areas: communication about events and waiting times.

Figure 2

Surveyed experiences of people participating in local collection events

| Percentage of people who responded positively | |

|---|---|

| I had a positive experience with New Zealand Police and the local collection event | 93% |

| I found the process easy once at the event | 93% |

| I had a positive interaction with collection event employees | 95% |

| I would recommend collection events to other firearms holders | 85% |

Source: Research First research report (October 2019), Firearms buy-back process review.

3.14

The Police collected information midway through the scheme that showed that the waiting time was less than 30 minutes for about half the people attending local collection events. The waiting times likely increased towards the end of the scheme, when there was an observed increase in the volume of firearms collected. This is consistent with the Australian Police's buy-back experience.

3.15

The number of formal complaints, including to the Independent Police Conduct Authority (IPCA), was low when compared to the total number of those taking part. As at 17 January 2020, the Police received 18 formal complaints out of more than 36,000 transactions.

There was a planned and co-ordinated approach to health and safety

3.16

The Police's approach to health and safety at local collection events was well planned and well co-ordinated. It was informed by risk assessments and a review midway through the scheme. A person at each event had overall responsibility for health and safety. There was a positive approach to reporting any incidents that could have caused harm and capturing lessons learnt from them, which reflected a good health and safety culture.

3.17

Loaded firearms were discharged in two incidents. Although these happened in a secure, non-public space, the effects could have been extremely serious. Fortunately, nobody was injured in either case. This brought to attention the need to strengthen the procedures to check that firearms were not loaded – in particular, those with tubular magazines. The Police provided staff with additional training after these incidents.

3.18

By the end of the scheme, there were 22 incidents that could have caused harm at local collection events. Of these, 17 involved ammunition that the Police and staff found after initial checks.

3.19

The Police told us that there were no arrests for disorderly behaviour at local collection events. Three participants at local collection events voluntarily removed themselves, and the Police had to remove only one person from an event.

The Police provided other ways for people to comply with the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme

Handing in firearms, magazines, and parts to dealers

3.20

The Police identified dealers' retail stores as important collection points. This was informed by the Australian buy-back scheme, which used dealers extensively. By working with dealers, the Police hoped to increase community engagement, build the public's trust and confidence in the scheme, and provide more opportunities for people to hand in firearms.

3.21

The Police worked closely with some dealers to design an approach that would work for the public, the dealers, and the Police. Some dealers agreed to allow people to hand in their prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts at their retail store. However, the Police's assessors assessed the firearms handed in to decide how much to compensate the owner. Dealers received a $50 administration fee for each buy-back application.

3.22

The Police and the dealers involved successfully piloted the approach to using dealers as a collection point in early September 2019. The Police then recruited dealers through an online "invitation to treat",10 which 60 dealers responded to. A Police evaluation panel reviewed the applicants. The panel approved 43 dealers to be part of the scheme.

3.23

From mid-September 2019, dealers participated in the scheme. However, they stopped taking newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts at the end of November 2019 because they had to prepare for the Christmas period. Also, towards the end of the scheme, the Police wanted to consolidate the ways firearms, magazines, and parts could be handed in. As at 21 December 2019, about 11% of all firearms collected was through dealer collection points.

Modifying firearms to make them comply with new regulatory requirements

3.24

Police-approved gunsmiths could modify newly prohibited firearms to comply with the new regulatory requirements. For example, a modification could reduce the number of rounds or cartridges a firearm can fire. Under the scheme, the Police subsidised modification work from Police-approved gunsmiths up to $300. Any modification work to a prohibited firearm must be permanent.

3.25

The option to modify a prohibited firearm became available in the scheme from mid-September 2019. Because the gunsmith industry is unregulated, it took some time for the Police to establish a list of authorised gunsmiths.

3.26

As with recruiting dealers, the Police used an online invitation. Through that process, 43 gunsmiths applied to be certified as a Police-approved gunsmith, and 34 were approved. An evaluation panel consisting mainly of police staff reviewed the applications.

3.27

The Police's provisional information, as at 21 December 2019, showed that 2717 firearms were modified through the scheme to comply with the new regulations. As at 13 February 2020, 1208 applications for modification were still to be completed.

Endorsements

3.28

Under the scheme, people were able to apply for an endorsement and permit to continue to legally own newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts. This includes people who need to use their firearm:

- for pest control or wild animal recovery;

- as part of a collection or as an heirloom or memento;

- for museum or theatrical use; or

- as a licensed dealer, or employee or agent of a licensed dealer.

3.29

People needed to apply for an endorsement from the Police before 20 December 2019. There was a $204 fee for the application.

3.30

The Police's provisional information shows that they had received 1750 applications for an endorsement as at 13 February 2020. Of these applications, 1022 applications were pending, 611 were approved, and 117 were refused.

3.31

The Police are prioritising their consideration of endorsement applications from people who most rely on an endorsement for their livelihood, such as professional pest controllers.

Compensating dealers for stocks of newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts has been challenging

3.32

The Police identified that, as at 29 November 2019, there were 517 licensed dealers in New Zealand. The new firearms regulations and the scheme will affect dealers differently, depending on the size and type of their business. At the time the scheme was being implemented, some dealers had a lot of newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts in stock.

3.33

Under the scheme, dealers could hand in their newly prohibited stock for compensation at cost (essentially, at wholesale or import price, including any direct or attributable costs) or, if dealers chose to return stock to suppliers, the difference between cost and the discounted refund. Dealers were prohibited from using local collection events to hand in, and receive compensation for, commercial stock.

3.34

Initially, dealers could hand in personal items (that were not part of their commercial stock) at local collection events. However, this was complex and time consuming because of the need to establish that these items were personally owned and not part of their stock. Instead, the Police decided that they would case-manage all dealer hand-ins and requested that dealers make a one-off submission for both personal items and dealer stock. These submissions were, and continue to be, managed by a central team.

3.35

The Police took some steps to mitigate the risk of dealers presenting commercial stock as personal items (that would be eligible for nearer to retail value compensation, rather than as commercial stock that was eligible to be compensated at cost only). These steps included:

- flagging the personal firearms licences belonging to people who also hold a dealer licence so that they could be asked appropriate questions if they attended a local collection event;

- performing a series of checks against the Police's records and other information that is available about a licensed dealer; and

- on-site interviews and formal investigations, where required.

3.36

At first, the control implemented to block dealers from getting compensation for their personal items at local collection events did not work – dealers were still able to hand in firearms at those events. That was later rectified. Until then, about 20% of dealers handed in personal items at local collection events.

3.37

As at 20 December 2019, the Police were intending to review the payments made for those items. The Police told us that their view is that dealers who handed in personal items at those events did so as fit and proper persons asserting that these items were personal property and not commercial stock.

3.38

The process for buying back dealers' personal and commercial stock was ongoing at the time of writing this report. Implementing the process has been more operationally challenging than the Police anticipated.

3.39

The Arms (Prohibited Firearms, Magazines, and Parts) Amendment Regulations (No 2) 2019 provided an explicit evidentiary threshold that a dealer had to meet to be entitled to compensation. This has been challenging for several dealers and requires the Police to provide high-level support to enable dealers to participate in the stock buy-back process.

3.40

The Police worked with some dealers to develop the process for compensating dealers. However, many dealers (especially dealers with smaller businesses) did not have sophisticated information systems to support this process.

3.41

Many of those dealers run small businesses that sell low numbers of firearms and have basic information systems. We understand that this has meant delays in receiving applications from dealers, and the Police rejecting some of those initial applications.

3.42

As at 13 February 2020, 1195 stock firearms had been collected. There is substantial work left to do to compensate dealers for their stock, with 144 out of 517 claims still being processed. The claims that still need to be processed include those from dealers with larger businesses.

3.43

Regulations were put in place that enable dealers to hold prohibited items after 20 December 2019, providing they have registered their intention to participate in the scheme before that date.

3.44

The Police's case-management approach involves working closely with dealers, talking through their applications, and resolving disagreements where possible. Formal resolution of disputes might involve legal action in the future.

3.45

The Police did not use their SAP system to track dealer stock. Instead, the Police used a dealer portal developed for the scheme, in combination with their standard emergency management information system used to task operational responses and provide case management of incidents. These systems did not support the same level of traceability of individual items as the SAP system.

The process for recruiting and training firearms assessors was robust

3.46

The Police employed independent contractors to assess firearms, magazines, and parts that people handed in to determine how much compensation would be paid.

3.47

Because assessors' decisions determined the amount of money people would receive for handing in their newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts, they were exercising a delegated financial authority on behalf of the Government. It was important that the Police recruited people with relevant skills, expertise, and experience and provided good training.

3.48

The Police advertised the assessor role to groups likely to have firearms expertise, such as the Army Reserves and those already in the Police's talent pool. The Police also accepted applicants referred by a police officer. The assessor role description had clear expectations about professional duties, service delivery and quality, knowledge of health and safety, and a focus on customer satisfaction and engagement.

3.49

Each applicant for the assessor role had to:

- demonstrate that they had significant knowledge and experience to make accurate assessments on the condition of firearms, magazines, and parts;

- pass the Police's standard vetting check;

- hold a current Firearms Safety Certificate;

- possess the temperament and personal qualities required for the role (which the Police assessed in interviews); and

- satisfy personal health requirements to perform prescribed duties.

3.50

The Police recruited people as assessors who had previously held positions such as Police-approved firearms instructors, armourers, dealers, and military roles.

Firearms assessor training

3.51

The main features of assessor training included:

- a detailed training needs analysis for each phase (prepare, collect, manage, and pay);

- a clear training and delivery plan, with subject-matter experts embedded throughout to help deliver a consistent approach;

- training resources specifically designed to facilitate alignment and co-ordination of the framework for identifying firearms, magazines, and parts and assessing their condition;

- clear separation of duties between the assessor role and other roles, such as the administrator; and

- using customer profiles to support the establishment of a customer-centric approach.

3.52

Assessors also received training and associated testing on:

- determining buy-back eligibility by applying the legislation;

- accurately identifying firearms, magazines, and parts in conjunction with the condition-assessment framework; and

- accurately communicating the rationale behind their assessment to firearms owners.

3.53

The risk of assessors having conflicts of interest (that is, the risk of an assessor assessing the value of a firearm of a person they know) was also carefully considered. Assessors were instructed to notify the senior police officer in charge if they knew someone handing in a firearm at a local collection event and to not be involved in assessing compensation for that person's firearms, magazines, or parts.

3.54

The Police's quality assurance over assessors included on-site monitoring and sampling assessments at local collection events, and central monitoring and sampling assessments after local collection events by examining photographs of the assessed firearms. EY recommended that the:

… Police keep a log of the assessments where a formal central-based quality assurance check was undertaken along with a record of any findings and associated actions. This should be supported by a minimum assessment requirement (with this being adjusted as required based on assurance assessment outcomes).

3.55

The information available to us suggests that complaints about assessors and technical errors in their assessments were low. This includes the low numbers of formal complaints about how the Police implemented the scheme to either the Police or the Independent Police Conduct Authority (IPCA). As at 17 January 2020, the Police had received 18 formal complaints.

3.56

The IPCA told us that it had received a very low number of complaints about alleged underpayment for firearms. It also recieved some complaints about police officers' attitudes. The IPCA told us that these complaints were all successfully resolved with the complainants.

Assessing unique prohibited items

3.57

From mid-September 2019, the scheme included the option for people to apply for a unique prohibited item assessment if they had a prohibited firearm that was not on the price list or a firearm that was on the price list but that had a significantly higher value. This was for items that were:

- rare or had distinguishing characteristics that significantly affected their value;

- otherwise unique and substantially different from any other listed prohibited item; and/or

- modified in such a manner and to such an extent that the owner had reasonable grounds to believe the value of the items was at least 30% more than the listed price.

3.58

There was a non-refundable fee of $138 to apply for a unique prohibited item assessment.

3.59

Applications were assessed by a panel (called the Unique Prohibited Items Advisory Panel), which included four mandatory members, a private sector commercial expert, an insurance expert, a valuation expert, and an international firearms expert.

3.60

The unique prohibited item assessment process was well documented, and the assessment panel operated in accordance with the documented process.

The Police's communication with the public was well planned and co-ordinated

The Police had a sound and well targeted communications plan

3.61

The Police had a comprehensive communications plan. It was informed by 20 "personas" likely to participate in the scheme. Examples included a "reactive confirmer" (a person who wishes to comply at the minimum level and is not deliberately difficult) and a "sentimentalist" (a person who has several firearms with significant financial or sentimental value attached and who might be reluctant to part with them).

3.62

The communications plan identified the likely behaviours of each persona and their information needs. Communication was, to some extent, tailored for each persona.

3.63

The Police regularly monitored the effect of their communications. They used multiple communications channels and targeted particular publications, radio, and television, and communicated directly with firearms owners and organisations. This included directly calling licence holders with an E endorsement on their licence. The Police used an 0800 number dedicated to questions about the scheme, which received more than 30,000 calls.

3.64

The Police provided extensive information about the scheme on their website, including videos. Some of that information was hard to navigate and some detailed, specific technical information was difficult to locate. Feedback we received from EY, the Council of Licensed Firearms Owners, and firearms owners shared this view. However, the information on the website about the process for getting an endorsement for a prohibited item was clear, comprehensive, and transparent.

3.65

Between 1 May and 20 December 2019, there were 939,000 page views of firearms-related content on the Police's website.

3.66

EY recommended that the Police "monitor the sentiment of the firearms community as a lead indicator for the success of the Scheme" and include that information as part of the broader reporting framework.

3.67

The Police have not included that information in their public dashboard reporting about the scheme. Apart from their survey of people at local collection events, the Police did not have a formal mechanism to monitor the sentiment of firearms owners during the scheme.

The disputes resolution process could have been communicated better

3.68

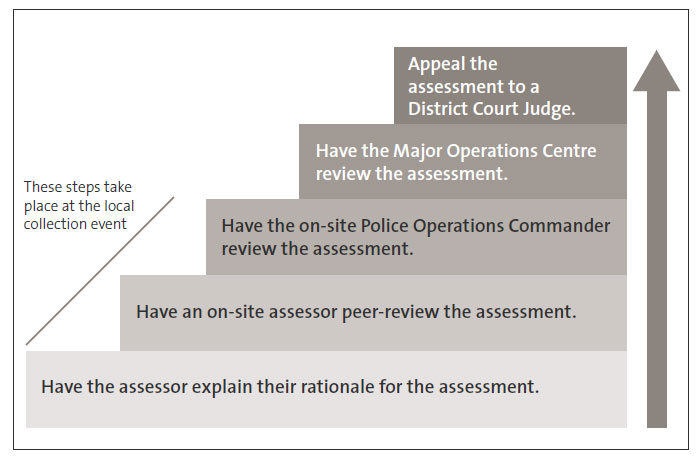

The Police had a standardised disputes escalation process for when a person did not agree with the amount of compensation offered for their firearm. The escalation steps are shown in Figure 3.

3.69

The escalation process for disputing an assessment at dealers' retail stores was the same, except that the assessors and Operations Commander were not on site.

3.70

The Police securely held prohibited items that were being disputed, and they were not made inoperative until the dispute had been resolved.

3.71

It would have been preferable if the Police had made information about the disputes resolution process more available so that it was clear that people could dispute assessors' decisions without appealing to a District Court Judge.

3.72

EY recommended that the Police increase the transparency of the dispute resolution process by putting more information about it on their website.

Figure 3

Steps a person could take to escalate a dispute about an assessment they disagree with

The steps someone could take to escalate a dispute about a firearms assessment were: having the assessor explain their rationale for the assessment, having an on-site assessor peer-review the assessment, having the on-site Police Operations Commander review the assessment, having the Major Operations Centre review the assessment, and, finally, appealing the assessment to a District Court Judge.

All handed-in firearms, magazines, and parts were securely destroyed

3.73

At local collection events, the Police made handed-in firearms inoperative on site. This was done by a machine press that bent and crushed the firearm in three places (the barrel, the receiver, and the stock).

3.74

Firearms handed in at dealers' retailer stores were stored safely for the Police's regional teams to collect and make inoperative.

3.75

The Police securely stored inoperative firearms that were handed in at Police locations. They were then transported to another location to be fully destroyed. We did not see evidence that any firearms, magazines, or parts in the Police's custody had been lost, stolen, or not accounted for. The Police performed a three-way reconciliation process between when items were collected and when they were destroyed to support this. There was no evidence of material gaps in this process.

3.76

The process included a final reconciliation between the SAP system information and the physical storage crates, and checking final shredded material for any remaining identifiable pieces that required re-shredding.

The firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme was supported by good systems and processes

3.77

The Police engaged SAP, one of their existing providers of information systems (including their finance and payroll system), to develop and support the SAP system to process applications and compensation payments. The SAP system also provided a means to track and trace firearms, magazines, and parts from the point they were handed in to final destruction. The SAP system was a strength of the scheme.

3.78

The Police's documentation for the SAP system identified and reported on risks and controls, and there was a comprehensive testing strategy.

3.79

On 2 December 2019, there was a privacy incident. The Police told us that a user accessed 436 citizen records, of which 34 were at a detailed account level (including bank account details and firearms licence numbers). The Police contacted all of the affected individuals and briefed the Privacy Commissioner and the Government Chief Digital Officer.

3.80

The incident occurred after an external provider updated the system in a way that the Police did not authorise. Although the Police did not make the unauthorised change to the system, the Police are ultimately responsible for the protection of private information.

3.81

The Police's response to, and management of, the incident was professional. Other government agencies provided the Police with good support when responding to the incident.

3.82

Local collection events were able to continue after the incident. The Police suspended public access to the SAP system (which people would use to register their intention to hand in prohibited firearms, magazines, or parts). Instead, staff in the Police's call centre and at local collection events had access to the SAP system and would enter that information after talking with a member of the public.

3.83

Although the incident might have affected public confidence in the scheme, members of the public continued to participate in local collection events.

3.84

The Police had adequate ICT controls over the systems managing the scheme. The controls included those over user access management, data loss prevention and system output, change management, IT disaster recovery, and network security and vulnerability management.

3.85

Penetration testing (that is, testing how easy the Police's systems were to hack) was done at the design stage of those systems and throughout the development of the system. The incident was not a result of those systems being hacked.

3.86

Access to the cloud-based SAP system databases supporting the scheme was tracked and reported on. Between September and December 2019, monthly access ranged from 99% (in November 2019) to 61% (in December 2019, reflecting the impact of a privacy incident and the decision to stop direct public access to the application).

Determining the level of compliance with the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme is difficult because of uncertainty about the number of prohibited firearms

Estimating the number of prohibited firearms

3.87

One of the most important ways to judge the effectiveness of the scheme is to determine the proportion of newly prohibited firearms and parts that were handed in.

3.88

To do this, we need to know how many prohibited firearms there are in the community. The previous regulatory regime focused on firearms owners instead of individual firearms. In part, because of this, the Police do not have accurate information about how many firearms there are in the community. Therefore, the Police can only provide estimates. Figure 4 shows the Police's estimates of the number of newly prohibited firearms.

Figure 4

The Police's estimates of the number of newly prohibited firearms in New Zealand

| Estimate by type of firearm | Total | Low estimate of prohibited number | High estimate of prohibited number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Estimate | % | Estimate | ||

| The Police's estimates as at 20 March 2019 | |||||

| Military-style semi-automatics | 13,175 | 100% | 13,175 | 100% | 13,175 |

| Rifles | 758,811 | 5% | 37,941 | 20% | 151,762 |

| Shotguns | 379,405 | 1% | 3,794 | 2% | 7,588 |

| All types | 1,151,391 | 5% | 54,910 | 15% | 172,525 |

| The Police's estimates as at 2 April 2019 | |||||

| All types | 1,200,000 | 5% | 60,000 | 20% | 240,000 |

| KPMG's estimates as at 7 June 2019 (commissioned by the Police and using volume estimates provided by the Police) | |||||

| Military-style semi-automatics | 14,286 | 100% | 14,286 | 100% | 14,286 |

| Rifles | 758,811 | 5% | 37,941 | 20% | 151,762 |

| Shotguns | 379,405 | 1% | 3,794 | 2% | 7,588 |

| All types | 1,152,502 | 5% | 56,021 | 15% | 173,636 |

| The Police's estimates as at 21 December 2019 | |||||

| Military-style semi-automatics | 15,037 | 100% | 15,037 | 100% | 15,037 |

Sources: New Zealand Police 2019, KPMG 2019.

Note: The numbers in bold are the numbers we refer to in this report when discussing the Police's range of estimates.

3.89

The only records of newly prohibited firearms were of military-style semi-automatics that were covered by an E endorsement.

3.90

However, because of deficiencies in how the information was recorded in the past, the Police's records of the numbers of firearms covered by an E endorsement are not certain, ranging at different times from 13,175 to 15,037.

3.91

It is important to note that not all centrefire semi-automatic rifles are covered by an E endorsement. Although the Police had a record of firearms covered by an E endorsement in private ownership, they did not know the number of other semi-automatics.

3.92

Some firearms could be relatively easily altered to, or from, a type of firearm requiring an E endorsement. For example, adding a previously unregulated large-capacity magazine to a semi-automatic firearm would make it a firearm that required an E endorsement. Removing a "bar" between the stock and trigger housing of a semi-automatic firearm so it had a free-standing trigger mechanism would also make it a firearm that required an E endorsement.

3.93

EY recommended that the Police take steps to better understand and manage the accuracy of their estimates of newly prohibited firearms. To do this, the Police commissioned the New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) to:

- review the current estimates of the amount of civilian firearms, including the proportion of those firearms that are now prohibited;

- clarify the confidence that can be placed on the estimates; and

- explore whether existing data sources could be used to improve the estimates.

3.94

NZIER assessed the information used for the different estimates of newly prohibited firearms against four criteria:

- reliability and consistency;

- validity and accuracy;

- verifiability; and

- bias.

3.95

NZIER concluded that only a low level of confidence could be placed in the different estimates of newly prohibited firearms. This was based on a medium level of confidence in the Police's estimate of the total number of firearms in the community, but a low level of confidence in the information about what proportion of the total number is made up of newly prohibited firearms.

3.96

NZIER found that it would be possible, with significant investment, to improve the reliability of the estimate of the total number of firearms and, to a lesser extent, the estimate of the number of newly prohibited firearms using existing data.

3.97

However, in NZIER's view, confidence in that estimate would remain low. This is because the ease of using parts to modify firearms makes the boundaries between prohibited and non-prohibited highly permeable, and because import tariff categories do not map readily on to what is or is not prohibited.

Quantity of collected firearms, magazines, and parts

3.98

The level of compliance with the scheme can be judged only against the Police's estimates of the total number of prohibited firearms in New Zealand. According to NZIER, these estimates have a low level of confidence.

3.99

The Police's provisional information about the number of prohibited firearms that have been collected or modified (61,332 as at 13 February 2020) is at the lower end of the Police's estimates of the total number of newly prohibited firearms (54,910 to 240,000).

3.100

As at 21 December 2019, nearly two-thirds (63%) of the firearms handed in (excluding dealer stock) were characterised as centrefire semi-automatics (valued at under $10,000), and a further 22% were rifles capable of firing 11 or more rounds from a single magazine (valued at under $2,000). Of the firearms handed in, 58% were assessed as being in new or near new condition. Only 2% were assessed as being in poor condition.

3.101

As at 21 December 2019, nearly one-tenth (8.7%) of firearms and only about 3% of parts collected in the scheme were collected for amnesty.

Most firearms covered by an E endorsement were accounted for

3.102

According to the Police's provisional information, 67% (10,009 out of 15,037) of firearms covered by an E endorsement were handed in as at 20 February 2020. A further 4211 were in the process of being assessed through the dealer buy-back, E endorsement application process, or as unique prohibited items.

3.103

Taken together, this means that 95% of firearms covered by an E endorsement (out of a total of 15,037) have been either collected or accounted for under the new regulations. The Police are actively following up on the remaining estimated 817 firearms covered by an E endorsement. Those firearms include those:

- that are legitimately being retained by licensed firearms owners for modification;

- that have become no longer prohibited because prohibited parts were handed in (for example, extendable magazines for shotguns);

- that people have indicated would be handed in but have not been and for which no endorsement has been sought; and

- where there are issues with the accuracy and/or currency of the recorded information.

3.104

Until the Police have fully completed processing the endorsement applications, all of the applicants will continue to hold firearms covered by an E endorsement. They must store them securely and not use them.

10: An invitation to treat is an invitation for people to express a willingness to participate. It is not legally binding.