Part 1: Why and how we did this work

1.1

We looked at how effectively and efficiently the New Zealand Police (the Police) implemented the firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme (the scheme).3 We did this because of the significant public interest in the scheme, its intended public safety benefits, and the amount of taxpayer money that funded it. We also wanted to provide the Police with feedback and the opportunity to act on recommendations while the scheme was running.

1.2

In this Part, we discuss:

- the scope of our work;

- how we approached our work; and

- how the scheme fits into the wider regulatory regime.

Scope of our work

1.3

This report assesses how the Police implemented the scheme. It does not evaluate the effect of policy changes on the regulation of firearms in New Zealand. It is outside our statutory mandate to comment on the merits of policy decisions.

1.4

The extent to which the policy changes will meet the objective of making New Zealand safer will only become apparent over time. We have recommended that the Police design and implement a framework to evaluate the effect these policy changes have had on making New Zealand safer (see Part 5).

1.5

We did not examine the Police's management and oversight of firearms regulation before the Christchurch attacks on 15 March 2019. Nonetheless, some of the matters raised in this report suggest that the Police experienced challenges in getting information about the operating environment under the previous regulatory regime for firearms.

1.6

We have examined the overall effectiveness of the Police’s implementation of the scheme. This included gaining an understanding of the systems and controls used to implement the scheme. We have not examined every transaction in the scheme, nor every judgement involved in each of those transactions.

How we approached our work

1.7

We assessed the effectiveness of the scheme's implementation according to the following six criteria:

- whether there were enough opportunities for the public to hand in or modify firearms, or apply for an endorsement, and whether the Police made sure that firearms owners knew about these opportunities;

- whether local collection events (public events where people could hand in their firearms, magazines, and parts) were well run and whether the public and police staff were kept safe;

- whether firearms owners received the compensation they were entitled to, were treated fairly, and received payment in a reasonable time frame;

- whether licensed firearms dealers (dealers) had enough opportunities to hand in prohibited stock and receive payment in line with the policy decisions;

- whether all firearms, magazines, and parts collected during the scheme were accurately recorded, tracked, and destroyed; and

- whether the number of firearms accounted for was in the range of the Police's estimates of the number of newly prohibited firearms in the community at the end of the scheme and whether all firearms covered by an E endorsement were accounted for.

1.8

Soon after the Government announced the scheme, we agreed that Ernst & Young (EY), our appointed auditor for the Police, would provide independent assurance about how the Police were implementing the scheme while it was running.4 This real-time assurance work meant that EY gave the Police regular feedback on how they were managing the main aspects of the scheme. We have drawn on the findings of EY's work and further analysis we carried out to assess how well the Police implemented the scheme.

1.9

The Police were open to receiving and acting on EY's feedback and recommendations as the scheme was running. That approach supported improvements to how the Police ran the scheme. To provide complete transparency on the work done, we encourage the Police to make the reports from the assurance work public.

1.10

EY provided real-time assurance feedback to the Police about:

- the planning and setting up of the scheme, including reporting requirements, resourcing, risk identification and management, and governance;

- how firearms assessors were selected, trained, and monitored;

- the process for resolving disputes;

- the exemption and endorsement process;

- the process for people to get their firearms modified to comply with the new legislation and associated statutory regulations;

- how unique prohibited items were dealt with;

- collecting dealers' stock of newly prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts and compensating dealers for it;

- the SAP5 system, including the process for managing and processing compensation payments and for what happens after a security incident; and

- how firearms were collected, stored, and destroyed.

1.11

EY's work involved:

- discussions with senior police officers responsible for the scheme, and contractors and other staff working on different aspects of the scheme;

- observing local collection events in Auckland, Christchurch, Dannevirke, and Masterton;

- visiting two dealers' retail stores in Auckland that were acting as collection points for prohibited firearms, magazines, and parts;

- observing the Major Operations Centre at Police National Headquarters;

- observing the process for transporting prohibited firearms to a location for final destruction and the destruction process;

- obtaining and reviewing documentation about the scheme and its operation; and

- providing the Police with 10 assurance reports and regular feedback as the scheme was being implemented, commenting on what was and was not working well, and providing recommendations.

1.12

The Police told us that EY's work helped them to implement the scheme consistently.

1.13

As well as drawing on EY's work, we also:

- interviewed senior police officers;

- met with representatives from the Council of Licensed Firearms Owners, Gun Control New Zealand, and the New Zealand Police Association to hear about their experiences of the scheme;

- reviewed various documents on the establishment and operation of the scheme;

- attended local collection events in Paraparaumu and Trentham; and

- reviewed about 60 emails we received from individuals, mainly firearms owners, about the scheme.

The firearms buy-back and amnesty scheme is part of a wider firearms regulatory regime

1.14

Although designing and implementing the scheme was a considerable task, it is only one part of the Police's regulatory responsibilities for firearms and firearms owners.

1.15

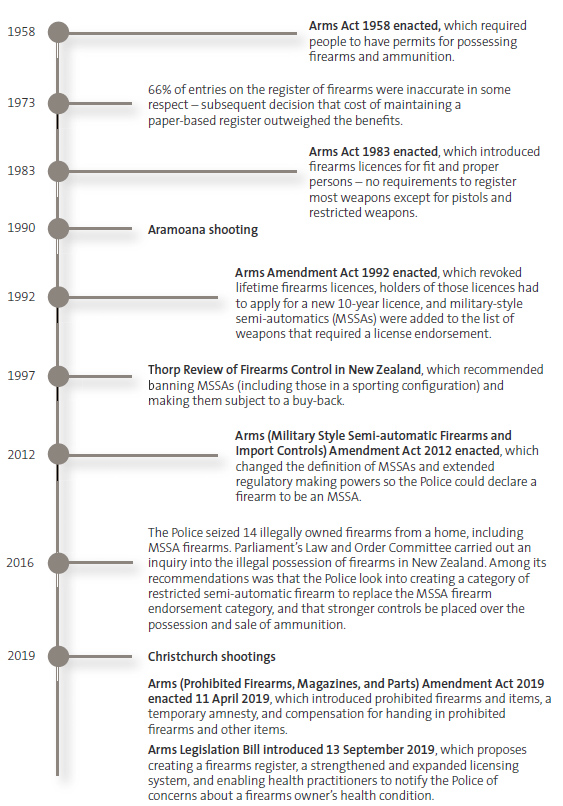

There is a long history of firearms regulation in New Zealand.6 Figure 1 shows that, throughout this history, the Police have been responsible for licensing owners of firearms, recording firearms, or some combination of both.

Figure 1

Selected milestones in New Zealand firearms regulation

The figure describes selected milestones in the history of New Zealand's firearms regulation, from 1958 to 2019.

Sources: Based on information from the April 2017 report of the Law and Order Committee Inquiry into issues about the illegal possession of firearms in New Zealand, the Arms (Prohibited Firearms, Magazines, and Parts) Amendment Act 2019, and the Arms Legislation Bill.

1.16

At the time of the Christchurch attacks, the Police were responsible for implementing the licensing system for firearms owners. This included managing the endorsement process. This is where licence holders could apply for an endorsement on their licence that would allow them to own certain types of firearms, such as military-style semi-automatics.

1.17

This endorsement was called an E endorsement. The Police kept a record of military-style semi-automatics used by licence holders covered by an E endorsement. There was no requirement for the Police to keep information about most other types of firearms held by licence holders, including semi-automatics that could be readily converted to a military-style semi-automatic firearm by adding unregulated large-capacity magazines.

1.18

The Police were also responsible for enforcing the firearms owner licensing and endorsement systems and for licensing dealers. They also had some responsibilities for regulating firearm imports and exports.

1.19

After the Christchurch attacks, changes were made to the regulation of firearms in New Zealand. The first suite of changes were the subject of the Arms (Prohibited Firearms, Magazines, and Parts) Amendment Act 2019. Those changes included introducing a scheme for handing in prohibited items. Parliament almost unanimously supported the passing of this legislation.

1.20

At the time of writing this report, a second suite of changes to the regulation of firearms and firearms licence holders had been proposed. These changes are outlined in the Arms Legislation Bill, which is currently being considered by Parliament. The Bill proposes a firearms register for all firearms and a strengthened and expanded licensing system for firearms owners.

3: We performed our work under sections 16 and 17 of the Public Audit Act 2001.

4: EY's assurance work was done under section 17 of the Public Audit Act 2001.

5: SAP is a German-based company delivering enterprise resource planning software, among other things.

6: For more comprehensive information about the history of firearms regulation in New Zealand and attempts to amend it over time, see A turning point for firearms regulation: Implications of legislative and operational reforms in the wake of the Christchurch shootings. This paper was authored by Nathan Swinton on an Axford fellowship to New Zealand. The paper is available on Fulbright New Zealand's website at www.fulbright.org.nz.