Part 3: Meeting young peoples' mental health needs

3.1

In this Part, we assess how well government agencies are meeting the mental health needs of young people. Our audit definition of "meeting need", set out in Figure 2, is our summary of the key components of what young people want in mental health services.26

Figure 2

The "meeting need" definition used in this report

| Rapid and barrier free | Rapid, barrier-free access to support – Access to barrier-free support when young people need it. Services in places and spaces where young people are – Such as schools, easy-to-access community locations, or online. |

| Tailored support | Youth-specific care – Services and models of care that are designed for young people. Youth voice and participation – Services that listen to and empower young people, recognise their strengths and mana, and include them in service design, delivery, review, and improvement. Youth-friendly environments – Services delivered in environments that are safe, welcoming, and inclusive of all young people. Services that reflect diverse young people – Inclusive services and a workforce that reflects young peoples' diverse identities and needs, with the option of separate services for some groups such as Māori and Pacific young people. |

| Relationships | Relationships – The importance of relationships and the ability to build ongoing relationships with trusted adults. Whānau-centred care – Involving whānau as partners in young peoples' care where appropriate. |

3.2

Appendix 2 has more information on how we applied this definition, including its specific relevance to Māori, Pacific, disabled, and Rainbow young people.

3.3

In this Part, we apply this definition of what young people want in services to five primary and specialist care settings commonly accessed by young people.27 These are:

- Primary:

- general practice medical centres (GPs);

- Youth-specific integrated primary care services (Youth One Stop Shops);

- school-based services;

- Access and Choice primary mental health and addiction services; and

- Specialist – infant, child, and adolescent mental health services (ICAMHS).

3.4

We expected agencies to:

- ensure that all young people have access to timely, barrier-free, and appropriate mental health support;

- understand and address the barriers young people might face to accessing mental health support by tailoring services to the specific needs of young people; and

- ensure that young peoples' input and participation is a part of mental health service design and delivery.

Summary of findings

3.5

Although GP visits are the usual first step in accessing mental health services in New Zealand, some young people face barriers to accessing GP care.

3.6

There is increasing evidence that youth-specific integrated primary services in schools and accessible community locations are effective youth-friendly alternatives to GP care for young people.

3.7

However, in our view more work is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of such services in New Zealand. Greater co-ordination between government agencies will also be needed to improve the consistency, reach, and sustainability of youth-specific integrated primary care services.

3.8

Investment into new primary mental health and addiction services is improving the availability of primary mental health and addiction support for young people with mild to moderate mental health needs.

3.9

However, young people are waiting longer to access specialist infant, child, and adolescent mental health services and capacity constraints in the specialist system are having a flow-on effect on primary services.

3.10

During our audit, we saw many examples of innovative services leading the way in including youth voice and participation and using youth- and whānau-centred service models. More work is needed by agencies to consider whether new and existing services appropriately incorporate youth voice and input.

3.11

In our view, more work is also needed to improve the quality and consistency of outcomes data collected by services, to ensure that planning and investment into mental health services is underpinned by sound evidence about what works for young people.

Some young people face barriers to accessing GP care

3.12

In New Zealand, most primary care is accessed through GPs and funded through a combination of patient charges and government subsidies. Children and young people aged 13 years and under can access a GP without charge. GP visits are the usual way people access more specialised services in the health system, including specialist mental health services.

3.13

It is common for people experiencing mental health concerns to see their GP first. A recent survey found that mental health and substance use concerns may make up a third of general practice consultations.28 General practitioners told us that mental health commonly comes up in their consultations with young people.

3.14

Although GPs remain an important avenue for young people to access mental health support, some young people face barriers to accessing GP care.

3.15

Young people aged 15-24 years visit GPs at the lowest rate of any age group in the population.29 Although the low rates of young people accessing GPs might be explained by the fact that young people typically experience better physical health than other age groups, young people also report high levels of unmet need for GP care.30

3.16

Known barriers faced by young people to accessing GP care in general include cost (for those aged 14 years and older) and lack of transport. Young people might feel embarrassed or ashamed to talk with their general practitioner about mental health concerns. They might worry about whether the information they share is confidential (even when it is).

3.17

Barriers to GP care are greater among Māori, Pacific, Rainbow, and disabled young people, those living in rural areas, and young people not in education, employment, or training.

3.18

The low rate of young people accessing GPs reflects global trends. Internationally, researchers have attributed low rates of young people accessing GP care to factors such as staff attitudes, young people not perceiving GP clinics as youth-friendly environments, and young people not feeling sufficiently involved in their care by their nurse or general practitioner.31

Integrated primary care models can make care more accessible to young people

3.19

Youth-specific integrated32 primary care models combine a range of primary physical, mental, and sexual health and other social and vocational services for young people in a single service. Examples of integrated youth primary health care models in New Zealand are Youth One Stop Shops and school-based health services. Although not youth-specific, whānau ora services also provide integrated support for rangatahi in their whānau context.

3.20

There is increasing international evidence to support the effectiveness of youth-specific integrated primary care services as an accessible alternative to GPs that meet a range of young peoples' health and well-being needs.33

3.21

An existing model for integrated youth-specific primary health and mental health care for 12-24 year-olds in New Zealand is Youth One Stop Shops. The model has existed in New Zealand since the 1990s and many Youth One Stop Shops have a high profile in their local communities. In 2021/22, Youth One Stop Shops received combined government funding of about $19 million.34

3.22

We spoke to staff at a range of Youth One Stop Shops as part of our audit. The model appears to meet many of the characteristics of what young people want in a mental health service. Youth One Stop Shop services are "for" young people (aged 12-24 years), are free, can be accessed without a referral, and offer a range of services that meet young peoples' holistic needs (that is, their physical, mental, vocational, and social needs) in one community location.

3.23

Locating multi-disciplinary teams on a single site allows for "warm" in-person handovers of young people to other professionals without the need for external referrals, which is a known risk factor in young people "falling through the gaps" between services.

3.24

Staff described to us a range of measures they take to create a service environment where young people feel comfortable and want to spend time. These include offering employment and mentoring to young people, offering kai and drinks to visitors, and running youth events and recreational programmes. The aim, as one youth health expert described it to us, is to help young people feel comfortable on good days so they show up on bad days.

3.25

Youth voice and participation is embedded into the service model of many Youth One Stop Shops, through mechanisms such as youth co-design, youth advisory groups, and employing young people on staff.

3.26

Young people played a leading role in developing the 502 Rangatahi Ora youth hub in Porirua. 502 Rangatahi Ora was established in 2021 as a collaboration between Te Rūnanga o Toa Rangatira, a local iwi organisation, and Partners Porirua, a non-government organisation (NGO).

3.27

The care model of 502 Rangatahi Ora emphasises building trust and genuine connections with young people and empowering them to make decisions about their lives. This service has a strong Māori and Pacific cultural focus, reflecting the input of the young people who took part in the co-design of the service.

3.28

The Youth One Stop Shop model was evaluated in 2009. The evaluators noted the overwhelmingly positive feedback that Youth One Stop Shops received from both staff and clients. However, the evaluators were unable to assess the model's effectiveness due to a lack of consistent outcomes data.35

3.29

Currently, Youth One Stop Shops are not available in all regions. There is also no consistent funding, objectives, outcomes data, or performance measures for Youth One Stop Shops nationwide.

3.30

Although some Youth One Stop Shops have a strong record of attracting rangatahi Māori, the model has not been specifically evaluated for its effectiveness with Māori.36

3.31

We also note that no universal integrated service is likely to work for all young people. The option of separate services is important for some groups, such as Māori and Pacific young people (see Appendix 2). Although school-based services can improve school students' access to primary care (see paragraphs 3.33-3.65), alternative options are needed for young people who are not in school.

3.32

In our view, an evaluation of Youth One Stop Shops and other community-based youth integrated primary care models should be carried out to compare the relative effectiveness of approaches to youth integrated primary care services and to inform the development of nationally consistent service guidelines.37

| Recommendation 2 |

|---|

| We recommend that Te Whatu Ora work with the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, Oranga Tamariki, and other agencies as relevant to evaluate the effectiveness of, and develop consistent guidelines for, the delivery of youth integrated primary health services. |

School-based services are critical to improving primary care access for students

3.33

The Ministry of Education and Te Whatu Ora fund health and well-being services in New Zealand secondary schools. Some secondary schools fund health services through other sources, such as annual operating grants.

3.34

Accessible integrated primary health care (including mental health) services in schools are important to overcoming the barriers that some young people can experience in accessing GP care.38

3.35

Individual schools are responsible for understanding and responding to any mental health needs that could affect student well-being or be a barrier to their learning. The Ministry of Education supports schools with this. In a 2023 survey, secondary school principals described supporting student mental health and well-being as the top challenge facing schools today.39

3.36

The Ministry of Education does not require schools to report back to the Ministry any data they might collect on the mental health needs of students.40

3.37

The Ministry acknowledges that "robust data" is necessary to understand student mental health needs and monitor service effectiveness but told us it must balance the need for improved data against other considerations, such as minimising reporting burdens for service providers and schools.

The Ministry of Education does not know how many students access guidance counselling services or how effective these are

3.38

The Ministry of Education acknowledges the many positive benefits from having mental health support in schools. Benefits include reduced mental distress, improved engagement and retention, increased student achievement, and reduced suicide risk.41

3.39

The Ministry of Education funds guidance counsellors in secondary schools through a "guidance staffing" entitlement calculated by roll size. The Ministry told us it spends about $95 million annually on guidance entitlement staff funding.42 Guidance counsellors employed using this staffing entitlement must be registered teachers. They usually also have a post-graduate qualification in counselling.

3.40

The Ministry of Education does not require schools to report on how they spent the guidance entitlement. The Ministry also does not set guidelines or standards for how many guidance counsellors schools should employ.

3.41

The ratio of counsellors to students appears to vary widely between schools, from 1:167 for a secondary school in the central North Island to 1:1150 for one large inner-city Auckland school.

3.42

Although the Ministry can tell from payroll data how many staff are employed through the guidance entitlement by region, it cannot tell how many services it is funding, if they are meeting students' needs, or whether schools are using guidance entitlement funding for its intended purpose.

3.43

The Ministry of Education has produced best practice guidance for schools on guidance counselling and pastoral care, Te Pakiaka Tangata.43

3.44

The Ministry's guidance in Te Pakiaka Tangata appears to reflect many of the characteristics of what young people want in mental health services, such as youth-friendly clinic spaces, youth input and participation, and the need for services to be culturally responsive. However, Te Pakiaka Tangata is guidance for schools and not mandatory.

3.45

The Education Review Office has previously expressed concern about the guidance counselling that is provided in schools. In a 2013 national review of guidance counselling, the Education Review Office described guidance counselling and pastoral care as "poor" in up to a third of secondary schools sampled, with some schools offering no counselling services.44

3.46

The New Zealand Association of Counsellors and the Ministry of Education co-commissioned a study that found most students who saw school guidance counsellors benefited from the service but that the students accessing counselling were mostly female and Pākehā.45 The study was based on a sample of 16 secondary schools.

3.47

The Ministry of Education acknowledges that it lacks evidence on how accessible and effective the guidance counselling model is for Māori and Pacific students.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Ministry of Education ensure that sufficient data is collected to understand the effectiveness of the school guidance counselling model for all students. |

Te Whatu Ora has expanded its school-based health services, but less than half of schools are eligible

3.48

Te Whatu Ora funds nurse-led school-based health services in about 300 decile 1 to 5 secondary schools.46 This covers about 35% of Year 9 to 13 students.47 However, most secondary school students (about 65%) are enrolled in decile 6 to 10 schools, where this Te Whatu Ora-funded service is not available.

3.49

School-based health services are made up of four components:

- the Year 9 home, education/employment, eating, activities, drugs and alcohol, sexuality, suicide and depression, and safety screening assessments;

- individual clinic time with students;

- external referrals; and

- health promotion activities in schools.

3.50

The time nurses spend on each of these activities varies between schools. Te Whatu Ora told us that about one in nine visits to school nurses in 2022 were for mental health concerns.

3.51

School nurses are expected to collect data from student screening assessments. However, school-based services are required to report only the percentage of assessments completed, not the data on student need that is identified through screening.

3.52

District health board control of school-based health services funding has led to a high level of regional variability in service delivery between eligible schools. The amount of funding per year for each student varied between regions. For example, in the Bay of Plenty it was $22 for each student and in Auckland it was $243 for each student. Nurse to student ratios between district health boards ranged from one nurse for every 400 students to one nurse for every 1500 students.

3.53

A youth health framework and self-review checklist is available to assist services to assess their responsiveness to students' needs in a range of domains, such as youth participation and youth-friendly clinic spaces. However, not all school-based health services have completed quality improvement plans based on this framework.48

3.54

Te Whatu Ora is aware of the funding, equity, and consistency issues with the school-based health service and are addressing these issues through an "enhancements programme".

3.55

This has involved working with the sector and a youth advisory group, Māngai Whakatipu, to refocus school-based health services and consider how well services meet the needs of priority groups such as Māori, Pacific, Rainbow, and disabled young people.

3.56

It has also included the co-design, with the youth sector and young people, of a new values-based framework, Te Ūkaipō. This will provide the basis for measuring and reporting school-based health service outcomes.49

3.57

However, we note that the current enhancements programme for school-based services applies only to schools eligible for the service. Most secondary school students are enrolled in schools that do not currently offer a Te Whatu Ora-funded school health service.

Greater cross-agency collaboration is needed to improve the consistency and efficiency of services in secondary schools

3.58

Research on school-based integrated primary health care services shows that they are most effective when delivered by well-resourced, multi-disciplinary teams that are integrated into the school setting.50

3.59

The buy-in and support of school staff and leadership is important – for example, to ensure that there are suitable clinic spaces for services, to facilitate student referrals to services and access to appointments in class time, and to promote awareness of services among the student body.

3.60

The involvement of several government agencies in funding health and well-being services in secondary schools increases the need for them to collaborate. This is to ensure that their objectives are complementary and aligned and the risk of duplication or inefficiency is reduced.

3.61

A promising recent initiative that has seen several government agencies work together to deliver primary health and well-being services to primary- and intermediate-age students was Mana Ake, funded by Te Whatu Ora.

3.62

Mana Ake began with a pilot in Canterbury in 2018. It is being rolled out to seven other regions, including Hawke's Bay and Tairāwhiti following the 2023 floods. Mana Ake in Canterbury is overseen by a joint leadership team made up of senior representatives from the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education, Te Whatu Ora Canterbury Waitaha,51 and local service providers.

3.63

An evaluation of Mana Ake in Canterbury described the critical factors in the programme's success as local co-design and effective cross-sector leadership that has made the most of existing networks.

3.64

The evaluators described the partnership approach taken by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education as "enrich[ing] the thinking of both sectors", with Ministry of Education input "essential to develop a wellbeing initiative that worked in school settings" while "Health sector involvement brought expertise in wellbeing interventions".

3.65

In our view, Mana Ake is a good example of agencies working together towards a shared vision incorporating the principles of local co-design. This could provide useful insights for other agencies when collaborating on integrated primary health and well-being services in school-based settings.

| Recommendation 4 |

|---|

| We recommend that Te Whatu Ora and the Ministry of Education work with other agencies as relevant to better align the objectives and operations of their school-based health and well-being services. |

Primary mental health support is now available to more young New Zealanders

3.66

Youth Access and Choice is one of four new service streams offered under the Access and Choice primary mental health and addiction initiative. Access and Choice aims to expand the range and choice of mental health support available for young people aged 12-24 years in primary care settings, addressing a key recommendation of He Ara Oranga to increase support options for people with mild to moderate mental health needs. Other Access and Choice service streams are the all-ages GP-based Integrated Primary Mental Health Service, the Kaupapa Māori service stream, and the Pacific service stream.52

Youth Access and Choice services has increased the range of primary mental health support available to young people

3.67

Youth Access and Choice aims to offer immediate, barrier-free, and accessible support to young people aged 12-24 years who are experiencing mild to moderate mental health concerns. Services that are part of Youth Access and Choice must offer a range of support options that are tailored to young people and their whānau and facilitate the transition to other services when required.

3.68

Te Whatu Ora told us that as of mid-2023, 22 Youth Access and Choice services were contracted and operational across all 20 former district health board districts. In October 2023, these services were providing around 5,200 individual or group sessions to 2,900 young people each month.

3.69

Te Whatu Ora expects that full roll-out of all Access and Choice services will be complete by June 2024. From June 2025, the end of the first full year of service delivery, Te Whatu Ora expects that 325,000 New Zealanders will have access to the new primary mental health and addiction services each year.

3.70

Youth Access and Choice funding has been used to establish new services and expand existing services. New services funded through Youth Access and Choice include He Kakano Ahau, a Northland-wide service delivered by local providers using the Te Ūkaipo framework that was prepared for school-based health services.

3.71

Existing services include Ease Up in Auckland, Waitematā, and South Waikato. Ease Up is a mobile youth primary mental health and addiction service delivered in partnership by a mix of mental health clinicians and peer support workers.

The Youth Access and Choice service meets many young peoples' service needs

3.72

The service specification for Youth Access and Choice reflects many of the themes of young peoples' feedback on what they want from mental health services.

3.73

Youth Access and Choice services use a range of innovative approaches to make their services attractive and accessible to young people. These include clinics in schools and accessible community locations, mobile services that travel to where young people are, and online or face-to-face options for engaging with mental health practitioners.

3.74

Youth Access and Choice services appear to be well integrated into local communities and can adapt to local needs. They also seem to be successful at attracting young Māori and young Pacific people as clients. Recent data shows that rangatahi Māori made up 33% of those using Youth Access and Choice services, while young Pacific people made up 11%.53

3.75

Some Youth Access and Choice contracts are held by Māori providers. Others cater specifically to the needs of rangatahi Māori by, for example, using a whānau ora approach. In addition, some Kaupapa Māori Access and Choice stream services have a specific focus on rangatahi, such as a Heretaunga (Hastings) service that connects with rangatahi through outdoor activities such as surfing and diving for kai moana.

3.76

Many Youth Access and Choice services demonstrate a strong commitment to youth voice and participation by, for example, embedding youth advisory groups into their governance structures. A recent evaluation of Youth Access and Choice has found the new services "champion" youth voice in service design and delivery and that young people accessing the services felt empowered to choose how, when, and where to access support.

3.77

Although the importance of youth voice and participation has been a major theme in young peoples' feedback during government consultation on the development of Youth Access and Choice, it is not a mandatory part of the Youth Access and Choice service specification.54 Te Whatu Ora told us that it plans to strengthen the emphasis on youth involvement in future contract variations for Youth Access and Choice.

3.78

Te Whatu Ora also told us it has developed a youth-specific outcomes tool for Youth Access and Choice, which it is currently trialling with a small group of providers. In the future, collecting outcomes data will be required of all Youth Access and Choice providers.

Youth Access and Choice has added to the complexity of the service landscape for young people

3.79

Youth Access and Choice services are part of a complex landscape of youth primary mental health and addiction services for young people.55 This includes primary and specialist services established by the former district health boards and delivered by primary health organisations and NGOs, as well as school-based health services.

3.80

In many cases, Youth Access and Choice contracts have been in addition to one or more existing contracts with existing providers of youth mental health or related services. This approach likely helped roll out much-needed support to young people more rapidly, as it allowed Youth Access and Choice to build on existing provider relationships and infrastructure.

3.81

However, the roll-out of Youth Access and Choice has added to the administrative burden on providers and made the service landscape more complex. This complexity can be a barrier for potential referrers or for young people wanting to access a service because it can make it harder to find out what support is available in their area.

3.82

Health agencies told us they see the centralisation of service commissioning under the health reforms as an opportunity to consolidate similar youth primary mental health contracts. Doing so would reduce duplication and the demands on community providers by streamlining the number of contracts they are required to report against. We support this.

3.83

Overall, we saw that Access and Choice services are beginning to make a significant difference by making youth-appropriate primary mental health support more available to young people across New Zealand.

3.84

The 2023 evaluation of the Youth Access and Choice service has found that the new service is generating good value for money by investing in early intervention supports for young people and that services are highly valued by young people and their whānau.

3.85

Overall, young people aged 12-24 years make up about 21% of people using Access and Choice services. Because young people make up about 17% of the population, this means that young people are over-represented among those accessing Access and Choice services.56

More work is needed to address capacity constraints in specialist child and adolescent mental health services

3.86

Infant, Child, and Adolescent Mental Health services (ICAMHS) provide specialist services to children and young people aged 0-17 years with moderate to severe mental health concerns. Specialist mental health services for young people aged 18 and older are provided through adult specialist mental health services. Te Whatu Ora ICAMHS for people aged 0-17 years are available in New Zealand's main centres and in many regional centres.

3.87

Although He Ara Oranga called on the Government to address the needs of New Zealanders with mild to moderate mental health concerns, it also told the Government that it must continue to prioritise access to services "for people with the more severe needs".

3.88

In particular, He Ara Oranga called on the Government to act with urgency to reduce waiting times for specialist child and adolescent mental health services. He Ara Oranga described increasing demand faced by such services as a "tidal wave of increased referrals".

3.89

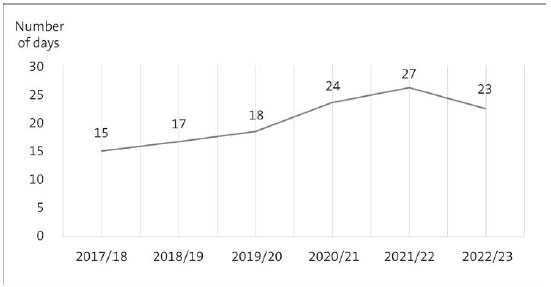

However, young people today are waiting longer to access specialist mental health services than they were when He Ara Oranga was published in 2018 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Average number of days 12-19 year-olds spend waiting, after referral, for their first appointment with a district health board specialist mental health service

Source: Data provided by Te Whatu Ora.

3.90

ICAMHS prioritise the care of children and young people who are clinically assessed as having acute or urgent care needs. Health agencies have provided us data that shows ICAMHS are continuing to provide timely care to young people in need of acute care, despite young people in this category increasing from 30% in 2015 to 36% in 2023.

3.91

However, the Ministry of Health told us that ongoing demand and capacity pressures have led to a raising of eligibility thresholds in many ICAMHS. This means that the level of urgency or severity of mental health need required to have an ICAMHS referral accepted might be higher than in the past.

3.92

Clinicians told us that young people not in need of urgent care can have severe overall needs due to the levels of distress they experience. This distress can affect their ability to function and participate in education and everyday life.

3.93

ICAMHS are expected to meet government wait-time measures for non-urgent referrals (80% of patients are seen within three weeks of referral and 95% are seen within eight weeks).57 Unlike equivalent adult specialist services, ICAMHS do not meet these measures. In 2023, 63% of young people aged 19 and under were seen within three weeks of referral, and 85% were seen within eight weeks.

3.94

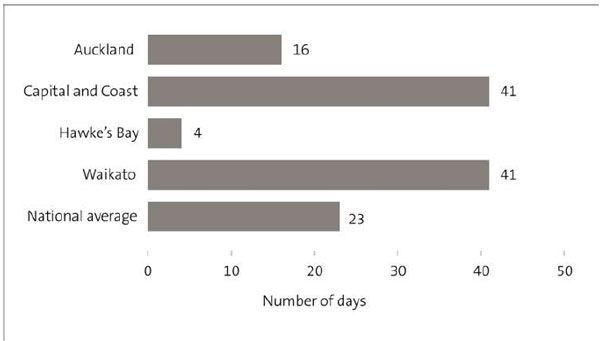

There is also considerable variation in how long young people wait to access ICAMHS in different regions. For example, in 2022/23 young people in Hawke's Bay waited four days on average for their first appointment with an ICAMHS clinician. By contrast, in the former Capital and Coast and Waikato District Health Board areas, the average waiting time was almost six weeks (see Figure 4).58

Figure 4

Regional variations in average days 12-19 year-olds spent waiting for a district health board specialist mental health service in 2022/23

Source: Data provided by Te Whatu Ora.

3.95

Long waiting times are a barrier to accessing mental health services. Research has linked long waiting times to a reduced likelihood of accessing mental health support, lower engagement and satisfaction with services, poorer outcomes, and inequitable service access because some people have a greater ability to "work the system".59

3.96

Services with long waiting times can take steps to improve young peoples' experience of care by offering interim support or treatment options for people waiting to be seen by a specialist.60 Some ICAMHS we spoke to provided examples of the support they provide to young people on waiting lists, such as regular phone-check ins or employing NGO providers to support young people on the waiting list. However, we heard that such supports are not universal across ICAMHS.

3.97

Specialist waiting times are not a reliable indicator of young peoples' overall need for specialist services due to the barriers many young people experience to accessing mental health support. Knowing that waiting lists are long can pose a barrier to referral. We heard that some GPs and schools are reluctant to refer young people to ICAMHS because of the long wait times.

3.98

Not all ICAMHS referrals are accepted. Te Whatu Ora provided us with data showing that the likelihood of a young person's referral to ICAMHS being accepted has declined – the proportion of declined referrals increased from 9% in 2012/13 to 14% in 2022/23.

Funding for child and adolescent specialist services has not kept pace with demand

3.99

Although funding for specialist services for children and adolescents has increased in the last decade, it has failed to keep pace with the increasing demand for services among younger age groups.

3.100

Documents provided to us by the Ministry of Health show that former district health board spending per year on specialist child and adolescent mental health services increased by 24% from 2011/12 to 2019/20, from $147.5 million to $182.3 million. Over the same period, the number of children and young people accessing ICAMHS increased by 30%.

ICAMHS are seeking to improve efficiency and reduce waiting times for young people

3.101

In recent years, many ICAMHS have adopted a United Kingdom model, Choice and Partnership, to manage demand and capacity and eliminate waiting lists for children and young people using specialist services.61

3.102

Choice and Partnership aims to streamline access to services by offering all children and young people and their families/whānau a timely "choice" appointment on referral. The clinician works with the young person and their whānau to agree on treatment goals. The clinician then presents "partnership options" based on those goals. Options include self-help strategies, referrals to other services, or staying with the specialist service.

3.103

Young people who choose to remain with the ICAMHS are booked in for a full series of "partnership" appointments for treatment or therapy. There is an emphasis on "letting go" (early discharge) after the support needs of the young person and their whānau are met.

3.104

Evaluations of Choice and Partnership suggest that it is likely to achieve its objective of eliminating waiting lists only if the model is fully implemented. Whāraurau, the government workforce centre for infant, child, and adolescent mental health, offers support and guidance for ICAMHS implementing Choice and Partnership.

3.105

However, we heard that many ICAMHS only partially implement the Choice and Partnership model. Part of the reason could be because fully implementing the model depends on external system factors, which individual ICAMHS have limited control over.

3.106

For example, fully implementing the Choice and Partnership model relies on referral or early discharge of some patients to other, typically primary-level, services. However, this can occur only if appropriate primary services exist and have capacity to take referrals. Clinicians told us they often struggled to find a suitable provider to discharge young people to, due to a lack of available services or frequent changes in NGO contracts.

3.107

A known risk associated with Choice and Partnership is that even if they receive a timely initial assessment, young people might wait for a long time for subsequent appointments (shifting the wait from before the first appointment to between the first and subsequent appointments).62 This can occur when services lack the capacity to meet demand and when clinicians are unable to discharge their patients to another service.

3.108

We asked Te Whatu Ora for data on the waiting times for first, second, and third appointments with ICAMHS because young people usually begin treatment at the third appointment (see Figure 5). The data shows that in 2022/23, a young person aged 12-19 years waited on average over 60 days (9 weeks) from the time of first referral until starting treatment.

Figure 5

Average number of days waiting for first, second, and third appointments for 12-19 year-olds referred to district health board specialist mental health services

| Year | Average wait time for first appointment (days) | Average wait time for second appointment (days) | Average wait time for third appointment (days) | Total average wait time (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017/18 | 15 | 20 | 17 | 52 |

| 2018/19 | 17 | 20 | 18 | 54 |

| 2019/20 | 18 | 21 | 19 | 58 |

| 2020/21 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 69 |

| 2021/22 | 27 | 27 | 23 | 77 |

| 2022/23 | 23 | 24 | 21 | 64 |

Source: Data provided by Te Whatu Ora.

3.109

When more young people presenting to an ICAMHS have acute needs, it can also affect the ability of ICAMHS to follow Choice and Partnership. The need to urgently see young people in crisis might lead to partnership appointments being delayed (see paragraph 3.103).

3.110

Documents we reviewed indicate that health agencies recognise the pressures facing ICAMHS to be primarily a problem of resourcing, rather than efficiency.

3.111

In a 2022 briefing to the then Prime Minister, Ministry of Health officials expressed their view that "the ICAMHS sector is delivering the best it can within current resourcing and circumstances, while also maintaining quality improvement efforts".

Capacity pressures within ICAMHS have flow-on effects for primary services

3.112

The previous Government expected that its investment in primary-level services will reduce demand on specialist mental health services in the long term.

3.113

It is too early to say how Government investment in primary services might affect specialist services in the long term. However, in the shorter term, we observed that capacity constraints in child and adolescent specialist services were having an effect on the ability of primary services (including some of the new Access and Choice services) to meet the needs of young people.

3.114

Youth One Stop Shops told us that an increasing proportion of the young people they see are either on waiting lists for specialist services or have had a referral declined. Young people in this category generally have more severe needs and might require longer and more intensive treatment, which Youth One Stop Shops are not resourced for.

3.115

Similarly, some Youth Access and Choice services report that high levels of demand from young people who cannot access specialist services are affecting their ability to provide timely accessible care to all young people who seek help. Some Youth Access and Choice services have introduced waiting lists.

3.116

We heard that when primary-level mental health services receive large volumes of referrals of young people with a high level of need, it can threaten their scope as a primary-level service offering immediate access to brief interventions for young people with mild to moderate needs.

Not all young people can access age- or culturally appropriate specialist mental health services

3.117

Eligibility for ICAMHS is currently restricted to people aged 17 and under. There is some flexibility to extend this upper age limit on a case-by-case basis.

3.118

Many young people accessing ICAMHS will not require ongoing treatment after their discharge from child and adolescent specialist services. Those who do must, in most cases, transfer to adult specialist mental health services from age 18.

3.119

Young people accessing ICAMHS receive care and treatment suited to their life stage and developmental needs. In adult specialist mental health services, young people might be expected to fit into models of care designed for older adults.

3.120

Many young people accessing ICAMHS find the transition to adult mental health services difficult, particularly the contrast in culture and practices from child and adolescent services.

3.121

Young people who described this transition to Te Hiringa Mahara Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission contrasted the more holistic, strengths-based approaches of ICAMHS with the overly diagnostic or medical-based model of adult mental health services that often offered few or no treatment options tailored to their needs as a young person.63

3.122

We heard that the requirement to transfer from child/adolescent to adult mental health services at age 18 takes place when young people are usually experiencing other major life changes, such as leaving school, or starting employment or further study, and is a key factor in young people being "lost" to services.

3.123

Health agencies acknowledge that adult mental health services might not be appropriate to the developmental and life-stage needs of young people, and that the transition to adult services is often challenging for young people and their whānau.

3.124

Te Whatu Ora intend to raise the age limit for child and adolescent mental health services to 24 years, with the ability to transfer to adult services voluntarily from age 20. However, Te Whatu Ora has not yet set a timeline for this change.

3.125

Options for Māori and Pacific young people to access a culturally specific ICAMHS are limited. Only some ICAMHS offer separate kaupapa Māori teams or services. We are aware of only one ICAMHS team catering specifically to the needs of Pacific young people. Most Māori and Pacific young people access "mainstream" ICAMHS.

3.126

Te Whatu Ora recognises that current investment in Māori ICAMHS is low in three of its four regions, and that there is a need to expand these services into more regions.

More work is needed to embed youth voice and participation into ICAMHS

3.127

Kia Manawanui highlights the importance of including the input of people with lived experience of mental health services into the planning, commissioning, delivery, and ongoing monitoring of mental health services.

3.128

Our conversations with those working in the mental health sector suggest that there is still a considerable way to go in embedding meaningful youth voice and participation into ICAMHS.

3.129

Some ICAMHS employ youth consumer advisors to represent young people who are current service users. However, not all ICAMHS have youth consumer advisor roles. In other services, the position is established but the role is not filled.

3.130

The experiences of youth consumer advisors varies between ICAMHS. Some youth consumer advisors we spoke to feel that their role is valued and that they can make a genuine difference. However, most stated they do not always feel that their roles are valued by clinicians or leadership. Some saw youth consumer advisor roles as tokenistic.

3.131

A common complaint of youth consumer advisors is being expected to provide meaningful input in extremely short time frames. This can make it difficult for them to consult with young people about a particular issue or decision. Many are employed for limited hours, such as one day a week, and this can also limit their influence on services.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that Te Whatu Ora, the Ministry of Education, Oranga Tamariki, and the Department of Corrections consider whether appropriate mechanisms for youth voice and participation are built into the design, delivery, and governance of new and existing mental health and well-being services for young people. |

Improvement is needed in the way specialist services measure outcomes for young people

3.132

Te Whatu Ora collects comprehensive service use data for specialist mental health services, including ICAMHS, through its PRIMHD64 dataset.

3.133

The PRIMHD dataset incorporates data on patient outcomes, which is completed by clinicians using a United Kingdom-developed mental health outcomes tool called the Health of the Nation Outcomes Scale, and the Alcohol and Other Drug Outcome Measure for adult community addiction services. A child- and youth-specific outcomes tool, Health of the Nation Outcomes Scale Child and Adolescent, is available.

3.134

In our 2017 report on mental health services, we found that low completion rates for Health of the Nation Outcomes Scale (including Child and Adolescent) reduced the reliability of outcomes data for specialist mental health services. Low completion rates remain a significant issue with the child and adolescent outcomes data.65 This was confirmed by our conversations with people in the sector.

3.135

We also note that Health of the Nation Outcomes Scale Child and Adolescent is a clinician-completed outcomes scale, which means it does not incorporate the voices of young people and whānau accessing services. This is a significant omission, as young peoples' perspectives on how well a service met their needs might differ from those of the clinician delivering the service.

| Recommendation 6 |

|---|

| We recommend that Te Whatu Ora, the Ministry of Education, Oranga Tamariki, and the Department of Corrections ensure that outcomes data is collected for all mental health and well-being services accessed by young people. |

Capacity constraints within specialist services limit the ability of specialist clinicians to support the rest of the system

3.136

Although specialist services such as ICAMHS are focused on people with a severe level of mental health need, they also support primary-level and front-line services.

3.137

Community outreach services are an important and established part of specialist mental health services. Their aim is to ensure that professionals in community settings (such as general practitioners and guidance counsellors) and other primary settings can readily access specialist support and advice as needed.

3.138

Community outreach services can take a range of forms, including training sessions for primary-level professionals (such as guidance counsellors) or co-locating specialist clinicians in primary services.

3.139

During our audit, we saw an example of community outreach in the close working relationship between Kāpiti Youth Support (a Youth One Stop Shop) and the local ICAMHS. These two services shared the care of some clients, had fortnightly joint assessments with Youth One Stop Shop staff and an ICAMHS psychiatrist, and ICAMHS clinicians provided professional supervision to Youth One Stop Shop staff.

3.140

Strong community outreach from specialist services has several benefits. Closer working relationships between primary- and specialist-level clinicians can help build the capability of staff in primary services and mutual understanding of each other's relative roles and expertise. It can reduce inappropriate referrals to specialist services and increase the confidence of specialist clinicians to transfer or discharge patients to primary-level services.

3.141

Close working relationships between primary- and specialist-level services can prevent the need for some young people to transition between services. Young people can stay with a primary-level service while benefiting from specialist-level care, as needed.

3.142

Although specialist clinicians recognised the value of community outreach, many told us that their heavy caseloads mean that they often could not spare time for non-clinical work. We heard that as capacity pressures have increased, some ICAMHS have been less likely to engage in community outreach activities than in the past.

26: Based on our discussions with established youth advisory groups, existing consultation documents that presented young peoples' input on similar topics, and our review of the significant body of youth mental health research that incorporates young peoples' views. To avoid the potential of harm, we did not speak to young people who are currently accessing mental health services.

27: We selected these five care settings on the basis that they are commonly accessed by young people or are specifically for young people.

28: Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners (2021), "Survey results raise concern for the health and sustainability of general practice", at rnzcgp.org.nz. Note that New Zealand does not collect standardised primary care data for health care accessed through GPs.

29: Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Survey 2022/23 annual data explorer: "Primary health care use indicator: Visited GP in past 12 months".

30: Ministry of Health, New Zealand Health Survey 2022/23 annual data explorer: "Barriers to accessing primary care" and Te Tāhū Hauora Health Quality & Safety Commission (2021), "Atlas of Health Care Variation: Health Service Access", at hqsc.govt.nz.

31: Over a third of New Zealand young people surveyed in 2018 reported that their general practitioner or practice nurse did not involve them in their care as much as they would have liked. See Te Tāhū Hauora Health Quality & Safety Commission (2021), "Atlas of Health Care Variation: Health Service Access", at hqsc.govt.nz.

32: Integrated care is defined as care that is "collaborative, co-ordinated, comprehensive, continuous, holistic, flexible and reciprocal" and where responsibility and accountability is shared. See Cross-party Mental Health and Addiction Wellbeing Group (2023), Under One Umbrella: Integrated mental health, alcohol and other drug use care for young people in New Zealand, page 29.

33: Hetrick, S et al (2017), "Integrated (one-stop shop) youth health care: Best available evidence and future directions", Medical Journal of Australia, Vol. 207, no. 10, pages S5-S18.

34: Cited in Cross-party Mental Health and Addiction Wellbeing Group (2023), Under One Umbrella: Integrated mental health, alcohol and other drug use care for young people in New Zealand, page 31.

35: Communio and the Ministry of Health (2009), Evaluation of Youth One Stop Shops, page 11. Some individual Youth One Stop Shops have also carried out their own evaluations to demonstrate the positive effects of their services.

36: Data provided to the Cross-Party Mental Health and Addiction Wellbeing Group indicates that rangatahi Māori make up 28-85% of young people accessing individual Youth One Stop Shops. See Cross-Party Mental Health and Addiction Wellbeing Group (2023), Under One Umbrella: Integrated mental health, alcohol and other drug use care for young people in New Zealand, page 23.

37: Also referenced in Cross-Party Mental Health and Addiction Wellbeing Group (2023), Under One Umbrella: Integrated mental health, alcohol and other drug use care for young people in New Zealand, page 25.

38: Denny, S et al (2017), "Characteristics of school-based health services associated with students' mental health", Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 0(0), pages 1-8.

39: Alansari, M et al (2023), Secondary principals' perspectives from NZCER's 2022 National Survey of Schools, page 29.

40: The Ministry of Education told us it is in the early stages of developing a student well-being measurement tool for use in schools.

41: The Ministry of Education (2017), Te Pakiaka Tangata: Strengthening Student Wellbeing for Success, page 8.

42: Based on estimated funding for 2023/24, supplied to us by the Ministry of Education. Other school-based programmes funded by the Ministry of Education include the Counselling in Schools initiative, which funds counselling services in about 200 primary and intermediate schools.

43: Ministry of Education (2017), Te Pakiaka Tangata – Strengthening Student Wellbeing for Success.

44: Although the Education Review Office has not repeated this national review, issues concerning a school's provision of guidance counselling and pastoral care may be raised in its reporting on individual schools.

45: Manthei, R et al (2020), Evaluating the Effectiveness of Counselling in Schools, page 11.

46: From 2023, the decile system was discontinued and replaced by an Equity Index. Te Whatu Ora informed us it has not yet decided how it will align school-based health service funding to the Equity Index.

47: Before the 2022 health reforms, school-based health services were funded by a combination of direct Ministry of Health funding and devolved funding to district health boards. School-based health services received $19.6 million of new funding from the 2019 Budget to cover decile 5 schools.

48: In 2017/18, only half of school-based health service providers submitted satisfactory quality improvement plans, as reported by district health boards.

49: Te Whatu Ora intended to begin training school-based health service staff in Te Ūkaipō from late 2023.

50: Denny, S et al (2017), "Characteristics of school-based health services associated with students' mental health", Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 0(0), pages 1-8.

51: Before the district health boards were disestablished in 2022, senior representatives from Canterbury District Health Board were part of the joint leadership team.

52: Initially commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Access and Choice services are now contracted and funded by Te Whatu Ora.

53: Based on the average percentage of Youth Access and Choice clients of Māori and Pacific ethnicity, 1:/11/2022 to 31/10/2023.

54: The Ministry of Health did not carry out specific engagement with young people as part of the development of Youth Access and Choice. It instead included a specific question about young peoples' preferences for mental health services as part of an existing consultation with young people that the then Ministry of Youth Development was carrying out for its Youth Plan in 2019.

55: These include youth primary mental health services established as part of the Prime Minister's Youth Mental Health Project 2012-2017, and those resulting from specific district health board or primary health organisation initiatives.

56: Te Hiringa Mahara Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission (2022), Access and Choice programme report: Improving access and choice for youth, pages 5-6.

57: Waiting times are calculated as the percentage of people who are referred to and seen by a specialist mental health service, having not been seen for at least a year, counted from the time the referral is received to the first appointment with a mental health professional.

58: Based on 2022/23 data provided by Te Whatu Ora on the average time a 12- to 19-year-old waited from referral to first appointment with an ICAMHS.

59: Te Pou (2022), Wait time measures for mental health and addiction services: Key performance indicator literature review, pages 10-11.

60: Te Pou (2022), Wait time measures for mental health and addiction services: Key performance indicator literature review, pages 12-13.

61: By 2013, 16 of New Zealand's 20 ICAMHS were reported to be using Choice and Partnership in some form. Choice and Partnership has also been adapted for use in Kaupapa Māori ICAMHS teams.

62: We note that this risk of internal wait lists developing is not unique to Choice and Partnership but is also a feature of traditional approaches to managing ICAMHS service capacity.

63: Te Hiringa Mahara Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission (2023), Youth Services focus report: Admission of young people to adult inpatient mental health services, pages 12-14.

64: Programme for the Integration of Mental Health Data. This includes government services and those provided by NGOs.

65: In the first quarter of 2023, only about 30% of 4-17 year-olds had outcomes data collected on admission to, and discharge from, community specialist mental health services, compared to a target of 80%. See Te Pou (2023), PRIMHD summary report – HoNOSCA: Health of the Nation Outcomes Scales – child and youth report for New Zealand, page 21.