Part 1: Introduction

1.1

Many young people in New Zealand enjoy good mental health and well-being. However, young New Zealanders experience the highest rates of mental distress of any age group in the population. Recent survey data suggests that the mental health and well-being of young New Zealanders has declined sharply over the past decade.6

1.2

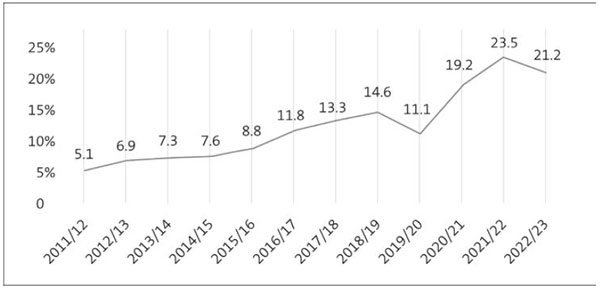

The New Zealand Health Survey for 2022/23 indicates that one in five 15-24 year-olds reported experiencing "high" or "very high" levels of mental distress in the past four weeks (see Figure 1). In a major survey of secondary school students, the percentage of young people who reported having experienced significant symptoms of depression increased from 13% in 2012 to 23% in 2019. New Zealand's rate of youth suicide is among the highest in developed nations.7

| We use a range of different terms in this report to refer to mental health, mental illness, and mental well-being. The terms "mental illness" or "mental health condition" refer to diagnosable conditions, which align with internationally recognised criteria. Examples include major depressive disorder, anorexia nervosa, and substance use disorders. The terms "mental distress" and "psychological distress" refer to a person's emotional state. A person who experiences mental distress will not necessarily meet the criteria for a diagnosable mental health condition. We use the terms "mental health needs" and "mental health concerns" as umbrella terms that encompass mental distress and diagnosable mental health conditions, including substance use disorders. Mental well-being is a broad concept. Young people and whānau experience positive well-being when they have a good quality of life, have what they need, have hope and purpose, and feel safe and connected to their communities. See Te Hiringa Mahara Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission's He Ara Oranga Wellbeing Outcomes Framework. |

Figure 1

Percentage of 15-24 year-olds who reported having experienced high or very high levels of distress in the past four weeks

Source: New Zealand Health Survey 2022/2023.

1.3

Female, Māori, Pacific, Asian, disabled, and Rainbow young people are more likely than other groups of young people to report experiencing mental distress.

1.4

New Zealand is not alone in facing these issues. High and rising rates of mental distress among young people are reported by many developed nations.

1.5

Most mental health conditions start in adolescence or early adulthood.8 Experiences of trauma and adversity in early life can be formative. Life transitions such as finishing school, starting work or further study, and leaving home can also place pressure on young peoples' mental health and well-being.9

1.6

Early evidence shows that young peoples' mental health and well-being has likely been affected more negatively by the Covid-19 pandemic and associated lockdowns compared with older age groups.10

1.7

In this Part, we describe:

- why we did the audit;

- what we looked at;

- how we did the audit;

- what we did not look at; and

- the structure of our report.

Why we did this audit

1.8

Investing in early intervention mental health services and support can help young people experiencing mental health concerns achieve their potential and reduce the lifelong impacts and costs of mental illness for individuals, whānau, and society. Early intervention is linked to a range of positive outcomes, including improved achievement in education, increased lifelong earnings, and greater life expectancy.

1.9

There is a high cost to not addressing mental health concerns as they emerge. People in contact with specialist mental health services die, on average, up to 25 years earlier than other New Zealanders.11 It is estimated that mental illness costs New Zealand about 5% of gross domestic product (GDP) annually.12 In 2023, this corresponded to almost $20 billion.13

1.10

The previous Government prioritised improving the well-being of children and young people aged 12 to 24 years. The goal of its Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy was to make New Zealand the best place in the world to be a child or young person.

1.11

Early in 2018, the Government launched an inquiry into mental health and addiction. The report from the Government inquiry, He Ara Oranga, was published in November 2018.

1.12

The Government considered the recommendations of He Ara Oranga together with those of the separate 2018 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development report Mental Health and Work in New Zealand.

1.13

The Government accepted, accepted in principle, or agreed to further consider 38 of the He Ara Oranga report's 40 recommendations and 18 of 20 recommendations made by the Mental Health and Work report.

1.14

The previous Government invested significant new funding into addressing mental health and well-being. The 2019 Wellbeing Budget included a $1.9 billion multi-agency investment into mental health and well-being over four years.

1.15

Young people were among the priority groups for the Government's multi-agency investment, which included $455 million of new funding over four years for the national roll-out of the Access and Choice programme. This programme aims to provide increased access to, and choice of, primary-level services for people with mild to moderate mental health and addiction needs.

1.16

In 2021, the Ministry of Health released Kia Manawanui, the Government's 10-year cross-agency strategy to transform the mental health and addiction system in response to the recommendations of He Ara Oranga. Kia Manawanui sets out the principles, focus areas, and system enablers to achieve He Ara Oranga's vision of mental well-being for all New Zealanders.

1.17

Since He Ara Oranga was published, government spending on mental health and addiction services14 increased from $1.47 billion to $1.95 billion annually (a 33% increase).

1.18

We wanted to know whether government spending on mental health services is making a difference for young people.

What we looked at

1.19

We looked at government agencies that support or provide services to young people with mental health concerns. They are:

- the Ministry of Health Manatū Hauora;

- Te Whatu Ora Health New Zealand;

- Te Aka Whai Ora Māori Health Authority;

- the Ministry of Education Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga;

- Oranga Tamariki Ministry for Children;

- the Department of Corrections Ara Poutama Aotearoa;

- New Zealand Police Ngā Pirihimana o Aotearoa; and

- the Ministry of Social Development Te Manatū Whakahiato Ora.

1.20

Our audit focused on how well these agencies:

- understand the mental health needs of young people;

- meet the mental health needs of young people; and

- work together to meet the needs of at-risk groups of young people.

1.21

To answer these questions, we looked at five care settings commonly accessed by young people. These settings are:

- general practices;

- youth-specific integrated primary care services (Youth One Stop Shops);

- school-based services;

- Access and Choice primary mental health and addiction services; and

- specialist infant, child, and adolescent mental health services.15

1.22

We also looked at how well government agencies work together to meet the needs of three groups of young people who experience greater risk of mental health concerns. These are:

- young people in care;

- young people not in education, employment, or training; and

- young people in the adult prison system.

1.23

We recognise that these are not the only groups of young people at heightened risk of mental health concerns. Other groups of at-risk young people include migrant and refugee people, homeless people, and young parents.

1.24

We also acknowledge that no individual or group is immune from mental health concerns.

1.25

Although the focus of our audit was on young people aged 12 years and over, there is strong evidence for the value and effectiveness of early intervention to address mental health and behavioural concerns in even younger age groups.16

How we did this audit

1.26

Seeking the views of young people has been an important part of our audit.

1.27

We spoke to a range of established youth advisory groups made up of young people who have used mental health services.

1.28

We have drawn on consultation documents that presented young peoples' input on similar topics. We have also made extensive use of youth mental health research that incorporates young peoples' views and perspectives.

1.29

We asked sector experts Dr Helen Lockett, Professor Cameron Lacey, and Romy Lee (a lived experience advisor) to review this report.17 Although their expertise informed our work, the findings and recommendations presented in this report are our own.

1.30

We held more than 150 discussions with about 400 people and groups from the government agencies listed in paragraph 1.19 and across the broader mental health sector. These people included frontline staff who directly support young people with mental health concerns and a range of academics and sector experts.

1.31

We looked at a range of documents, including publicly available reports and research and documents requested from government agencies.

1.32

Appendix 1 sets out more information about our audit methodology.

What we did not look at

1.33

We did not look at:

- mental health and well-being programmes aimed at preventing, or educating young people about, mental illness;

- the effectiveness of, or appropriateness of clinical decisions about, young peoples' care or treatment; or

- wider social determinants or causes of poor mental health and well-being in young people.

1.34

To avoid potential harm, we did not speak to young people who are currently receiving treatment from mental health services.

1.35

Although this report is focused on mental health services, we recognise that young peoples' mental health and well-being is partly shaped by their environment. For this reason, mental health services can be only a part of the solution to preventing and responding to mental distress in young people.

The structure of our report

1.36

In Part 2, we discuss how well government agencies understand the mental health needs of young people.

1.37

In Part 3, we discuss how well government agencies meet the mental health needs of young people in five key care settings.

1.38

In Part 4, we look at how well government agencies are working together to meet the needs of three groups of at-risk young people.

1.39

In Part 5, we look at how well government agencies are addressing key system constraints that affect their ability to meet young peoples' mental health needs.

6: Sutcliffe, K et al (2023), "Rapid and unequal decline in adolescent mental health and well-being 2012-2019: Findings from New Zealand cross-sectional surveys", Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 57, no. 2, page 280, and Fleming, T et al (2020), Youth19 Rangatahi Smart Survey, Initial Findings: Hauora Hinengaro/Emotional and Mental Health, pages 1-3.

7: Sutcliffe, K et al (2023), "Rapid and unequal decline in adolescent mental health and well-being 2012-2019: Findings from New Zealand cross-sectional surveys", Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 57, no. 2, page 267 and UNICEF Office of Research Innocenti (2020), Worlds of Influence: Understanding What Shapes Child Well-being in Rich Countries, page 13.

8: Solmi, M et al (2021), "Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies", Molecular Psychiatry, Vol. 27, pages 281-295.

9: Gluckman, P (2011), Improving the Transition: Reducing Social and Psychological Morbidity During Adolescence, and Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit (2016), The Prime Minister's Youth Mental Health Project: Summative Evaluation Report, page 17.

10: World Health Organization (2022), World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All, page 31 and Bower, M et al (2023), "A hidden pandemic? An umbrella review of global evidence on mental health in the time of COVID-19", Frontiers in Psychiatry, Vol. 14.

11: Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction (2018), He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction, page 29 and Cunningham, R et al (2014), "Premature mortality in adults using New Zealand psychiatric services", New Zealand Medical Journal, Vol. 23, no. 127, pages 31-41.

12: Organisation for Economic Development (2018), Mental Health and Work: New Zealand, page 26.

13: Based on total 2023 GDP of $395 billion. See New Zealand Government (2023), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2023, page 181, at treasury.govt.nz.

14: Our audit encompassed both mental health and addiction (alcohol and other drug) services for young people. We refer to these collectively in this report as "mental health services".

15: Other settings where young people might access services which were not a focus of this report include Accident Compensation Corporation-funded services, inpatient services, paediatric services, adult community specialist mental health services, crisis services, emergency departments, and youth justice and forensic services.

16: Gluckman, P (2011), Improving the Transition: Reducing Social and Psychological Morbidity During Adolescence, pages 9-10.

17: See Appendix 1 for more information about our reviewers.