Part 4: Full assessment of applications

4.1

In this Part, we:

How the full assessment of eligible applications was carried out

4.2

The full assessment phase ranked and prioritised applications so that the Tourism Recovery Ministers could compare and make decisions based on the merits of the applications.

4.3

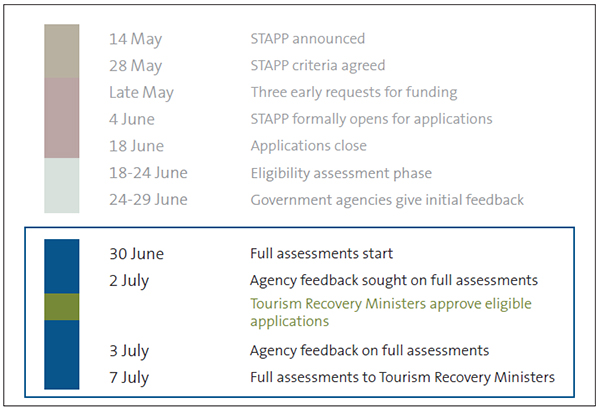

The time frame for this process was short. The Tourism Recovery Ministers approved the eligible applications on 2 July 2020. The Ministry had until 7 July 2020 to carry out full assessments and peer review them, get feedback from other agencies, moderate decisions, and present the recommendations to the Tourism Recovery Ministers in time for a meeting on 9 July 2020. Because of the time frame, the Ministry started the full assessments shortly after finalising the eligibility assessments, and before the Tourism Recovery Ministers had formally approved the eligibility assessments.

4.4

The Ministry told us that there was a lot of variation in the information submitted by tourism businesses. This caused difficulty considering the short time frames of the application and assessment processes. We reviewed a sample of assessments to see how consistently those applications were assessed against the criteria.

Several factors informed the assessment

4.5

Applications were scored against the STAPP criteria on a scale of 1 to 5. The Ministry assessed how significant the tourism business was to its region based on visitor numbers. One consequence of this was that zoos, museums, and art galleries became strategic assets. The Ministry told us it had not anticipated this. However, the Ministry followed the criteria it had designed to maintain consistency.

4.6

When assessing spill-over benefits to the region, the Ministry focused on financial benefits, such as whether it supported other businesses or employed people. The Ministry looked at broader information that tourism businesses provided about how it contributed to the community. However, the Ministry did not do further research.

4.7

We asked the Ministry whether it considered council-owned assets were eligible for STAPP. This is partly because, in our view, it would be difficult for council-owned assets to establish that they had exhausted all other avenues of support. The Ministry told us that it had raised this with the Tourism Recovery Ministers and was told that council-owned assets should be considered.

4.8

We asked the Ministry whether it considered the allocation of funding at a regional level. The Ministry told us that assessments were based on the individual applications, but it did provide advice to the Tourism Recovery Ministers on what the regional impact would be if they funded the top 50 or 100 applicants.

4.9

Although there was an assessment for whether a tourism asset was culturally, historically, or environmentally significant, no scores were assigned to these criteria.

Financial analysis

4.10

The Ministry commissioned Deloitte to carry out financial analysis of the applications. Because of the time constraints, Deloitte had to begin this before the Tourism Recovery Ministers met to approve eligible applications.

4.11

Deloitte carried out several checks, including a credit check, and extracted a common set of financial information from up to two years of profit and loss information in the application. Deloitte noted any gaps for the Ministry to follow up, noting how the amount of funding requested would be used in one of four pre-defined categories, and calculated a set of financial ratios that showed the trend in earnings and the amount of funding requested relative to the earnings. Deloitte calculated scores for each tourism business based on these ratios, and provided the Ministry with a worksheet that ranked applications on the basis of the financial ratios. Tourism businesses were given a lower score if they were asking an amount of funding that seemed disproportionately large compared with its pre-Covid revenue.

4.12

Deloitte noted the variability of the information it received. Larger tourism businesses tended to have easy access to robust financial information, whereas some smaller tourism businesses did not.

4.13

Deloitte told us that it reviewed the funding requested and flagged matters in applications that needed further investigating. The Ministry had to decide whether to investigate further or to request additional information to assist the assessment. If the information requested was not provided, the application became ineligible as the assessment was considered incomplete. The Ministry told us that one tourism business provided insufficient information. The Ministry said it made several attempts to get the information it needed but the business did not provide it, which resulted in the application not progressing.

4.14

The Ministry told us that this financial analysis provided a "reasonableness check" of what the tourism business was requesting and provided assurance that the business had been financially viable before Covid-19.

Agencies' and New Zealand Māori Tourism feedback on applications

4.15

On 2 July 2020, the Ministry gave other agencies and New Zealand Māori Tourism the suggested rating scores for applications to review and provide feedback on by 3 July 2020. At that time, the team working on STAPP was unaware of the Ministry's secure file transfer system. This meant that to view the actual applications (which contained commercially sensitive information), the agencies had to go to the Ministry's offices.

What did the agencies say?

4.16

New Zealand Māori Tourism and the agencies that reviewed the assessments had a focus specific to their background and knowledge (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

The focus of government agencies when considering applications

| Government agency | Agency focus |

|---|---|

| Tourism New Zealand | Tourism New Zealand focused on significant tourism assets. It relied on its knowledge of the tourism sector to advise on the international reputation and visitor numbers of tourism businesses. |

| Department of Conservation | The Department of Conservation focused on the environmental contribution of tourism assets. The Department of Conservation noted which operators were engaged in environmental or conservation activities such as breeding programmes, pest control, and waste minimisation. |

| The Ministry for Culture and Heritage | The Ministry for Culture and Heritage focused on the cultural and historical significance of tourism assets and how they contributed to the broader cultural and historical landscape. |

| Te Puni Kōkiri | Te Puni Kōkiri focused on the social and cultural significance of specific Māori tourism assets. |

| New Zealand Māori Tourism | New Zealand Māori Tourism focused on the cultural significance of specific Māori tourism assets and what they contributed to the broader community. |

4.17

In some instances, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage endorsed the amount of funding requested, questioned the rationale for the amount of funding requested, or questioned what other sources of funding were available to businesses, such as the Provincial Growth Fund. The Ministry for Culture and Heritage recommended that the Ministry increase its rating for some applications. This advice was adopted in most, but not all, cases.

4.18

New Zealand Māori Tourism pointed out the local and regional social, economic, and environmental contributions that the tourism businesses made. It also pointed out the significance of the unique cultural experience that the tourism businesses were offering. It described these businesses as going beyond more formulaic "haka, hāngi and hongi" experiences. New Zealand Māori Tourism did further analysis to understand the structures behind business names and which businesses shared the same parent company.

4.19

Although New Zealand Māori Tourism's focus was primarily on Māori tourism businesses, it also commented on other tourism businesses that had a significant impact (employment and training opportunities and flow-on business effects) on Māori communities.

4.20

New Zealand Māori Tourism identified inconsistencies in how the assessment criteria were applied, particularly with respect to assessing whether an asset was nationally or internationally recognised. New Zealand Māori Tourism noted that the Ministry rated 10 Queenstown/Southland tourism businesses as being top attractions for the region (and therefore eligible for the maximum score available). However, Rotorua only had two tourism businesses in the top 53, and one business in the top 75 assets. New Zealand Māori Tourism recommended increasing some of the Ministry's ratings. This was done in some cases, but not in others or only partly. 16

4.21

New Zealand Māori Tourism told us that the STAPP criteria were likely to result in Māori tourism businesses scoring relatively low marks because the criteria ultimately focused too much on awarding high points based on the number of tourists. In its view, this was inconsistent with the desired "future state of tourism" that had been developed, which had a goal for lower volume but higher-quality tourism offerings.

What did the Ministry do with that advice?

4.22

We asked the Ministry how it responded to feedback from other agencies. The Ministry said it was "disciplined" about looking at what was relevant. Where comments were out of scope, the Ministry did not take this into account and focused on the criteria.

4.23

Where an agency said that an asset was culturally significant, this information was incorporated into assessments that were provided to the Tourism Recovery Ministers.

Moderation of the full assessment phase

4.24

The Ministry had peer review processes to ensure that assessments were carried out consistently, and a moderation process to identify and address any anomalies.

4.25

The Ministry identified clusters of applications such as aviation, jet boats, kayaking, and museums. The Ministry tried to make sure that they had been treated consistently and any differences were assessed. The Ministry said that for the aviation, kayaking, and accommodation industries, it tried to ensure that there was consistency through comparative analysis and moderation of these assets. The Ministry's legal team participated in the moderation meeting to ensure that it was done impartially and correctly.

4.26

We saw a couple of exceptions where tourism businesses that should have been ineligible made it through to the full assessment process. These were identified and removed.

4.27

The Ministry worked at speed to review agency feedback over the weekend and incorporated this in its advice to Ministers on 9 July 2020.

Our comments on the full assessment phase

4.28

Because of the short time frames Ministry officials were working under, we did not expect perfection. However, we looked for what steps the Ministry took to ensure that there was consistency in the assessment process and that decisions made on a high-trust basis were accompanied by good verification later.

4.29

Tourism businesses applying for STAPP funding were not given detailed instructions about the information they needed to provide or what format it needed to be in. Both the Ministry and Deloitte told us that there was inconsistency in the nature, extent, and quality of information that tourism businesses provided. This made making direct comparisons between applications more difficult.

4.30

The Ministry had a standardised assessment process that harnessed the same key information for all tourism businesses. Deloitte used a standardised assessment framework and rating tool for the financial assessment.

4.31

Because of technology constraints, as well as the short time frames, other agencies had limited access to information about the applications. This might have limited their ability to give feedback. However, the feedback that agencies provided indicated that, in most cases, the agencies had a good understanding of the nature of the tourism businesses being assessed and the unique contribution that they made to the work of other agencies. These views were recorded in the documents that went to the Tourism Recovery Ministers to support their decision-making.

4.32

Although the cultural, historic, and environmental significance of the tourism businesses was part of the assessment process, no rating was applied to these factors. The assessment was based on whether one or more of those factors was present. Because this was one of the key areas that other agencies were providing input into, we expected these factors to be scored. This might have disproportionately affected Māori tourism businesses that had tourism offerings centred on unique cultural, historic, or environmental experiences.

Funding decisions

4.33

We reviewed a sample of assessments to see how consistently the Ministry assessed these applications against the criteria at the eligibility phase and full assessment phase. We analysed samples of two types of tourism business: aviation and kayaking. These were two segments of the tourism industry where people raised complaints with us about the STAPP process. From what we saw, the Ministry applied criteria evenly across similar tourism businesses in the same category.

4.34

We wanted to understand the methodology behind the amount of funding awarded and how consistently this was applied.

4.35

We compared the Ministry's worksheets (which contain some financial analysis, the amount applicants requested, and the calculated minimum viability amount nominated by the tourism business) against the funding decisions that were ultimately confirmed by the Tourism Recovery Ministers.

4.36

We looked for discrepancies and excluded the tourism businesses that were awarded a total grant or loan amount that matched what they asked for in their application. We reviewed the remaining tourism businesses against the full financial analysis and commentary that Deloitte provided to see if there was a reason for the difference between the amount tourism businesses asked for and the amount the Ministry recommended to the Tourism Recovery Ministers. For example, Deloitte advised that in some cases tourism businesses had asked for less funding than would be required so they could operate at a minimum viability level. This might be because they intended to hibernate the business.

4.37

The Ministry told us that when determining funding for Māori tourism businesses, it considered advice from New Zealand Māori Tourism about the recommended funding amount. Only 5.5% of Māori tourism businesses received more funding than they had sought. This is compared with 30.5% of non-Māori tourism businesses that received more funding than they had sought. Less funding was offered to Māori tourism businesses compared with other tourism groups with revenue in a similar range.17

4.38

Of the 126 applications we reviewed:

- 22% were awarded the amount they requested in their STAPP application;

- 27% received more funding than they requested;

- 51% received less funding than they requested; and

- 40% received funding for minimum viability level operations.

4.39

Tourism businesses that were funded less than the minimum funding amount that they requested raises the question of whether the funding would be adequate to keep them viable and was good value for money.

4.40

There might be other information we are not aware of that would explain these discrepancies – for example, final sums might have been reduced because of negotiations between the Ministry and businesses or the Ministry reduced the final sum because funding was requested for items that were out of scope. Overall, given the variation in outcomes, it was not clear to us that the decisions about final funding amounts had a consistent and documented framework.

4.41

In our view, the fast assessment process ultimately resulted in slower decision-making. This is because the Tourism Recovery Ministers began to understand some of the limitations that the short time frames had imposed on the assessment process.

16: Of the New Zealand Māori Tourism recommendations, three were accepted, four were partially accepted, and nine were not accepted.

17: Out of 18 Māori tourism businesses, only one was awarded more funding than it sought. Four businesses (22%) received the amount they sought, and 13 (72%) received less than sought. Only three of the Māori tourism businesses that received less than they sought were awarded funding that aligned with the minimum viability amount.