Part 1: Introduction

1.1

In September 2021 the Treasury published its most recent long-term fiscal statement, He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021.2 Under the Public Finance Act 1989, the Treasury is required to prepare a long-term fiscal statement at least once every four years.

1.2

Including He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, the Treasury has published five long-term fiscal statements since 2006.3 We have previously commented on the Treasury’s 2013 and 2016 statements.

1.3

Under the Public Service Act 2020, the Treasury is also required to prepare a long-term insights briefing at least once every three years.

1.4

The Treasury chose to include the information needed for its first long-term insights briefing in He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021. We refer to this integrated document as “the 2021 Statement”.

1.5

In introducing the 2021 Statement, the Secretary to the Treasury said that integrating the long-term insights briefing and the long-term fiscal statement provided an “opportunity to analyse key trends and their potential long-term financial impacts directly alongside a range of policy options available to address them”.4

What we looked at

1.6

In this commentary, we set out to understand how well the Treasury identified and summarised long-term insights about the challenges and opportunities facing the Government, and how well it integrated those insights into an outlook of the Government’s long-term financial position. We also considered how well the 2021 Statement assists the Government in making good financial decisions and increases the quality and depth of public information.

1.7

We have not sought to provide assurance over the information in the 2021 Statement. Our comments are based on our review of the 2021 Statement, background papers, and other relevant literature. We also talked with Treasury staff involved in preparing the 2021 Statement, obtained expert advice, and used the guidance from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (the DPMC) on long-term insights briefings.

1.8

The expert advice was provided by Professor Norman Gemmell, Chair in Public Finance at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington. His advice focused on the financial projections in the 2021 Statement and the underlying models and assumptions.

1.9

The Auditor-General does not comment on government policy except when reviewing how well particular policies are implemented (for example, their effectiveness and efficiency). Where we refer to policy choices in this commentary it is only to assess the extent to which they are adequately identified and discussed in He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021. We do not discuss the merits of any policy option.

1.10

Various terms can be used when talking about financial projections. For clarity, we use:

- “financial” instead of “fiscal”, except when referring to the Treasury’s long-term fiscal statements or the fiscal strategy, or when quoting other people’s work; and

- “projection” instead of “forecast” or “prediction”.

1.11

In this Part, we:

- consider the importance of developing long-term projections;

- outline the legislative requirements for the Treasury to prepare a long-term fiscal statement and a long-term insights briefing;

- discuss the purpose of these documents and their place in the public financial management system;

- summarise what previous long-term fiscal statements have told us;

- outline the key messages from the 2021 Statement; and

- outline what we cover in the rest of this report.

The importance of long-term projections

1.12

Boston, Bagnall, and Barry recently observed that “New Zealand faces formidable long-term challenges – economic, social, environmental and technological”. They also said that “[h]ow well these are tackled by current and future governments will have profound implications for the wellbeing of the nation’s citizens”.5

1.13

Short-, medium-, and long-term projections inform decision-making about how to respond to those challenges and opportunities. It is what “distinguishes reasoned planning from blind action”.6

1.14

Despite the uncertainty inherent in these types of projections, they can provide meaningful information about the likely scope and scale of possible future scenarios (such as combinations of earthquakes, population ageing, and floods) and the likely social, environmental, and financial implications that may need to be managed.

1.15

This allows for better-informed policy choices about what actions to take in response and when that action is required.

1.16

Projections are useful for understanding and planning for the long-term resilience and financial sustainability of government. As Gluckman and Bardsley observe, “[b]ad things will happen”, and a systematic and transparent approach is needed to identify and manage these risks.7

1.17

However, developing projections can be challenging at a whole-of-government level, particularly with the current difficulties arising from Covid-19. Our comments should be read with this in mind.

The legislative requirements for long-term fiscal statements and insights briefings

1.18

The Public Finance Act 1989 sets out the requirements for long-term fiscal statements. The Public Service Act 2020 sets out the requirements for the long-term insights briefing. We summarise the requirements for each of these documents below.

The long-term fiscal statement

1.19

One of the main objectives of the Public Finance Act 1989 is to help improve public sector performance by promoting “responsible fiscal management” through increased transparency and greater accountability.8

1.20

Part 2 of the Public Finance Act 1989 encourages responsible fiscal management by requiring the government to adhere to certain financial management principles. It also requires regular and periodic financial reporting from the Treasury and the Minister of Finance.9

1.21

This reporting allows current priorities and spending intentions to be compared with what has happened in the past and considered against what may happen in the future. It helps the government to answer questions such as what is prudent, what is stable, what is predictable, and what is sustainable.10 These are all important for responsible financial management.

1.22

Section 26N of the Public Finance Act 1989 requires the Treasury to prepare a statement on the long-term fiscal position of the government as part of this periodic reporting.

1.23

The Secretary to the Treasury is responsible for preparing these statements at least once every four years. The Public Finance Act 1989 does not specify the statement’s content or how it should be prepared. It requires only:

- a statement of responsibility asserting that the Treasury has used its best professional judgements about the risks and the outlook; and

- disclosure of significant assumptions underlying any projections.

1.24

The Treasury’s Guide to the Public Finance Act says that the long-term fiscal statement:

…is intended to lead to more comprehensive reporting of the issues that could adversely impact on fiscal sustainability and in this way to assist the Government in making decisions that are consistent with the principles of responsible fiscal management.11

1.25

According to the Treasury, the purpose of the long-term fiscal statement is to:

… increase the quality and depth of public information and understanding about the long-term consequences of policy decisions and to assist governments in making fiscally-sound decisions.12

The long-term insights briefing

1.26

The 2021 Statement is also the first long-term insights briefing to be prepared under the Public Service Act 2020.

1.27

Stewardship is one of the main principles of the Public Service Act 2020. The public service is expected to look ahead and provide advice to the government on future challenges and opportunities. Preparing long-term insights briefings is an important part of the public service’s stewardship role.

1.28

According to the DPMC, the value of the briefings is “the opportunity to identify and explore the issues that matter for the future wellbeing of the people of New Zealand”.13

1.29

Clauses 8 and 9 of Schedule 6 of the Public Service Act 2020 require departmental chief executives to publish a long-term insights briefing at least once every three years.

1.30

There are three main requirements for long-term insights briefings. In summary, these are:

- They must be independent of ministers.

- They must make available in the public domain:

- information about medium- and long-term trends, risks, and opportunities that affect or may affect New Zealand and New Zealand society; and

- impartial information and analysis about those matters, including policy options for responding to them.

- Each chief executive must consult with the public on the subject matter to be considered and the draft briefing. They must then take that feedback into account when finalising the briefing.

1.31

Although the Public Service Act 2020 refers to the medium and long term, it does not define these in years.

The purpose and place of He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021

1.32

The Public Finance Act 1989 provides a set of principles, accountability requirements, and mechanisms designed to improve transparency and accountability and place greater focus on the longer term.

1.33

In a background paper to the 2013 long-term fiscal statement, the Treasury discussed the reasons for the fiscal responsibility provisions in the Public Finance Act 1989. The paper noted that the main motivation for the focus on responsible financial management was:

… a response to shocks (such as Britain going into the Common Market and the 1970s’ oil price shocks), unaffordable policies (such as Think Big, or supplementary minimum prices for sheep meat) and the inevitable consequence: huge external indebtedness and lower living standards. These fiscal provisions reflected a resolve never to be so exposed and vulnerable again.14

1.34

Without an effective longer-term lens, the strategic priorities and objectives of the government could become short-term and narrowly focused.

1.35

As Boston, Bagnall, and Barry note, there are:

… incentives in democratic systems for policy-makers to prioritise short-term interests over those of future generations … governments need to understand the long-term challenges and risks they face, ascertain how best to respond, and implement the required policies.15

1.36

The purpose of the long-term fiscal statement and of the long-term insights briefing are closely aligned. Together with other reports such as the investment statement and the well-being report, they form part of the suite of stewardship reports designed to improve the quality and depth of public information, and inform the government’s strategic priorities and fiscal strategy.

1.37

We discuss these two ambitions below.

Informing the government’s strategic decision-making

1.38

The main ways for governments to give effect to the resolve to “never to be so exposed and vulnerable again” are through policies, strategies and the decisions they make as part of annual Budget processes.

1.39

According to the Treasury, the Budget process can be divided into five distinct phases. The first two are the strategic phase and the decision phase.16

1.40

The strategic phase allows the government to consider and balance many competing priorities, all with a finite set of resources in mind. The results of this phase are reflected in the government’s Budget Policy Statement.

1.41

The decision phase allows the Treasury to assess the priorities and initiatives that the government puts forward and also provide recommendations on them.17

1.42

The result of these two phases is a set of broad strategic priorities, policy goals, long-term well-being objectives, and financial projections that describe the government’s financial plans over the short, medium, and long term. These are set out annually in the Budget Policy Statement and the Budget.

1.43

These phases rely on bringing together sources of information about:

- the government’s progress and past performance;

- current spending intentions and priorities; and

- what issues and priorities could be important in the future.

1.44

Sources of information that relate to government progress and past performance include:

- the Public Service Commission’s three-yearly report on the state of the public service;

- the annual audited financial statements of the Government;

- the Treasury’s four-yearly investment statement; and

- the Treasury’s four-yearly well-being report.

1.45

Sources of information that relate to current spending intentions and priorities include:

- Parliamentary scrutiny processes (such as the annual Budget authorisation process);

- the Treasury’s twice-yearly economic and fiscal updates (which provide a projection for the next five years); and

- wider government strategies and policies and current issues (such as Covid-19).

1.46

Sources of information that relate to what the future may hold include:18

- departments’ three-yearly long-term insights briefings; and

- the Treasury’s four-yearly long-term fiscal statement.

1.47

The choices made during the Budget process about public spending, tax, and borrowing, and the balance between them, will affect New Zealand’s economic, social, and environmental outcomes and the government’s long-term financial resilience and sustainability.

Improving the quality and depth of public information and engagement

1.48

The long-term fiscal statement and the long-term insights briefing are also intended to improve the quality and depth of public information and understanding about the government’s long-term opportunities, challenges, and policy choices.

1.49

The Treasury has wide discretion about the content and form of the long-term fiscal statement. However, the DPMC provides comprehensive guidance about the focus and the preparation of long-term insights briefings.

1.50

Long-term insights briefings are intended to be public facing, consultative, and focused on the matters that are important for New Zealanders’ intergenerational well-being. An important requirement for preparing long-term insights briefings is the public’s opportunity to contribute to which topics each briefing will cover and to the draft briefing after it has been prepared.

1.51

The Treasury told us that it saw the long-term insights briefing and associated consultation as potentially useful for informing long-term analysis of the government’s financial position.

1.52

We agree. We expected that integrating the two reports could provide more relevant and accessible information to better inform the Government, Parliament, and the public about the long-term issues that matter to New Zealanders.

Insights from previous long-term fiscal statements

1.53

This is the fifth long-term fiscal statement that the Treasury has published since 2006. It prepared all of them in different economic conditions – including times of challenge and recovery (for example, after the global financial crisis and the Canterbury earthquakes).

1.54

All four statements raised “red flags” about the effects that an ageing population could have on the government’s long-term levels of net debt. The 2016 long-term fiscal statement also considered the relationship between long-term public finances and intergenerational well-being, noting that “sustainable government finances are a precondition to improving long-term living standards”.19

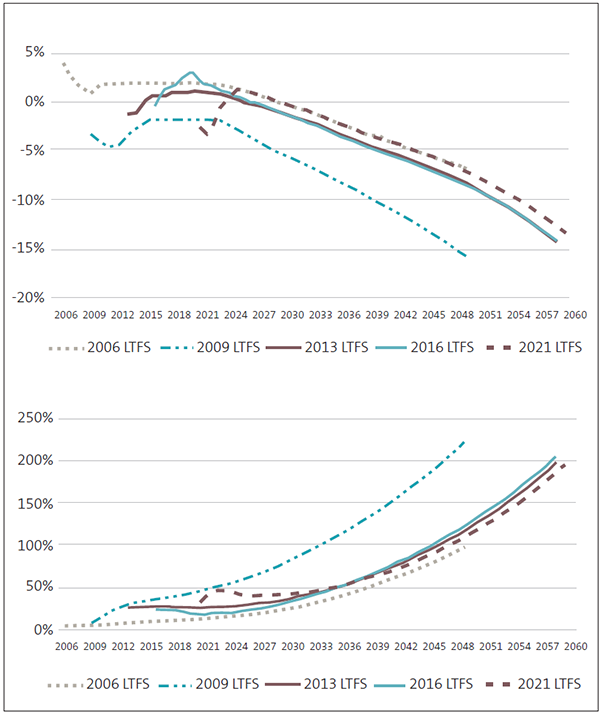

1.55

Figure 1 shows the projections of the core Crown’s operating balance and core Crown net debt from each of the previous four statements.20 We have also added the 2021 projections for comparison purposes. Net debt shown here excludes the New Zealand Superannuation Fund assets. If they were included, the projections of net debt would be lower.

Figure 1

The core Crown operating balance and projections of net debt from the Treasury’s long-term fiscal statements

Source: The Treasury’s long-term fiscal models for 2006, 2009, 2013, 2016, and 2021.

1.56

The past projections show that, regardless of the financial position that the government starts from, an unsustainable level of operating deficit and net debt will occur over each statement’s 40-year projection. For each long-term fiscal statement, this is because of the effects of an ageing population on the costs of superannuation and healthcare.

1.57

However, this unsustainable situation only arises if future governments:

- do nothing about these increasing costs, other government spending, the level of tax revenue, or the operating deficits arising from the above; and

- do nothing but borrow to fund those operating deficits (and the increasing interest costs).

1.58

The assumptions underlying these projections point to various financial options to address the problem of rising debt. Previous long-term fiscal statements presented most of these options. For example, governments could:

- lower the cost of superannuation by increasing the age of entitlement;

- reduce spending on other activities;

- increase the tax rate; or

- fund a greater share of spending on superannuation through the New Zealand Superannuation Fund.

1.59

From a financial perspective, these options are clear. However, more analysis is needed to fully understand the effect of these options on wider aspects of well-being.

1.60

A conference held as part of the public consultation for the 2013 long-term fiscal statement discussed how the long-term fiscal statement process could support policy reform. In his opening address to the conference, Professor Buckle observed that, although there is clear evidence of a long-term demographic challenge, achieving enduring policy reform is difficult. One of his proposals was to use the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework, with its (then) four well-being capitals, as criteria to evaluate policy options against.21

1.61

The 2016 long-term fiscal statement made some attempt to do this. However, in comparison, the 2021 Statement provides relatively little analysis.

The main messages in He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021

1.62

The Treasury published the last long-term fiscal statement in 2016. It planned to publish the next statement in March 2020 and had already completed a significant amount of work at the end of 2019.

1.63

However, the emergence of Covid-19, and the likelihood that it would have a significant economic and financial impact, meant that the Treasury sought and received an extension to the required four-year time frame.

1.64

This extension gave the Treasury until the end of September 2021 to publish the 2021 Statement. It also provided an opportunity to integrate the processes and information needed for the Treasury’s first long-term insights briefing.

1.65

Bringing together and commenting on the implications of long-term projections that summarise and combine the many different activities and policy choices of governments is a challenge. However, what these projections tell us about the future profile and capacity of the Government’s financial resources is fundamental to responsible public financial management.

1.66

Central to the 2021 Statement is an understanding of the Government’s financial sustainability. This is defined in He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021 as:

… the ability for the government to continue to fund the services and transfers it provides on an ongoing basis into the future without requiring major adjustments in expenditure or revenue settings.22

1.67

Governments should not incur unsustainable levels of debt. This is because doing so:

- “… would impose costs on the wellbeing of future generations that could reduce the quality of the public services they receive, or increase the taxes they pay”;23 and

- not allow shocks and natural disasters to be managed “as effectively as possible, imposing additional costs on them at what would already be a challenging time”.24

1.68

The following are the 2021 Statement’s main messages:

- The financial implications of the Government’s response to Covid-19 are largely temporary and will not have a material impact on the Government’s long-term financial position.25

- As a result of population ageing (and the effect that this has on health and superannuation spending), the government’s net debt will become unsustainable over the long term if nothing is done. As shown in Figure 2, the final net debt projection in 2061 is 196.9% of GDP. Alternatively, if net debt is held constant at about 48% of GDP, core Crown revenue (mainly taxes) will have to rise from 29.1% of GDP in 2021 to 38.9% of GDP by 2061 (see Figure 3).26

- Other shocks, such as recessions, earthquakes, and further pandemics, are also likely in the future. The Government’s financial position is relatively resilient to these shocks.27

- Climate change will have significant economic and financial impacts. However, the scale of those impacts is uncertain, partly because some policy decisions are still to be made.28

- The Government has choices about the level of debt to target in the future – policy options considered to achieve those targets include managing healthcare spending, increasing taxes, and/or responding to demographic change.29

- These policy options could provide a more sustainable level of debt. However, although improving financial sustainability helps maintain and improve intergenerational well-being, it may be detrimental to population groups who already face challenges accessing health services or an adequate income in retirement.30

Structure of this commentary

1.69

In Part 2, we consider the usefulness of the long-term insights briefing and the benefits of integrating it into the 2021 Statement.

1.70

In Part 3, we discuss the benefits and usefulness of the long-term financial projections and what they tell us.

1.71

In Part 4, we summarise our findings and consider the overall value of the 2021 Statement in informing the strategic objectives and decisions of the Government, and in improving the quality and depth of public information and engagement

2: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021. The Treasury also published background papers alongside He Tirohanga Mokopuna, and we refer to these where relevant.

3: See www.treasury.govt.nz.

4: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, page 4.

5: Boston, J, Bagnall, D, and Barry, A (2019), Foresight, insight and oversight: Enhancing long-term governance through better parliamentary scrutiny, Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, page 186.

6: Aaron, H J (2000), “Presidential address – Seeing through the fog: Policymaking with uncertain forecasts”, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Vol 19, No 2, pages 193-206

7: Gluckman, P and Bardsley, A (2021), Uncertain but inevitable: The expert-policy-political nexus and high-impact risks, Koi Tū: The Centre for Informed Futures, The University of Auckland, pages 3 and 21.

8: Part 1A(2)(c) of the Public Finance Act 1989. The Act also covers lines of accountability, parliamentary scrutiny, and reporting obligations.

9: The Treasury (2019), A guide to the Public Finance Act, page 33.

10: In terms of responsible financial management, stability can refer to the stability of tax rates.

11: The Treasury (2019), A guide to the Public Finance Act, page 42.

12: See “New Zealand’s long-term fiscal position” at treasury.govt.nz.

13: See “Long-term insights briefings” at dpmc.govt.nz.

14: The Treasury (2013), Long-term fiscal projections: Reassessing assumptions, testing new perspectives, Wellington, page 32.

15: Boston, J, Bagnall, D, and Barry, A (2019), Foresight, insight and oversight: Enhancing long-term governance through better parliamentary scrutiny, Institute for Governance and Policy Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, pages 34 and 36.

16: See “Guide to the Budget process” at www.treasury.govt.nz.

17: The third, fourth, and fifth phases of the Budget process include preparing the documents needed for the Budget in May, obtaining Parliamentary support for the Budget, and any subsequent amendments to the Budget, where additional appropriations are needed during the year.

18: There is also other public reporting about future opportunities and challenges in the public sector. For example, the DPMC maintains a register of National Security Intelligence Priorities.

19: The Treasury (2016), He Tirohanga Mokopuna – 2016 Statement on the Long-Term Fiscal Position, page 6.

20: The operating balance is the difference between total revenue and total expenses – plus gains or losses in the market values of government assets and liabilities.

21: Buckle, B (2012), “Policy development and the role of the Long-Term Fiscal External Panel: Opening remarks to the Affording Our Future Conference”, 10-11 December 2012, Victoria University of Wellington, pages 5 and 6.

22: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, page 44.

23: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, page 44.

24: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, page 44.

25: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, pages 5 and 9.

26: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, pages 19 and 21.

27: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, pages 30 and 34.

28: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, page 5.

29: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, page 2 (Contents).

30: The Treasury (2021), He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021, pages 7, 13, 35, 43, 54, and 59.