Part 3: Governance and oversight

3.1

In this Part, we discuss:

- the government leadership of the SDGs;

- central government's roles and responsibilities for the SDGs;

- plans to assist implementation of the SDGs and monitoring progress towards achieving them; and

- reporting arrangements for the SDGs.

3.2

Because of the significance and broad reach of the SDGs, and the complex issues they address, we expected to see clear leadership within government to drive their implementation. We expected there to be a plan for implementing the SDGs and monitoring progress towards achieving them, which would also describe agencies' roles and responsibilities for individual SDGs and for the SDGs overall.

3.3

The 2030 Agenda states that monitoring and reporting is important to track progress towards achieving the SDGs. It also sets out the expectation that, by 2020, data should be sufficiently disaggregated to ensure that progress can be monitored, particularly for vulnerable groups.

3.4

We expected to see a set of indicators that define what the Government wants to achieve and that can be used to measure progress for all the SDGs, with disaggregated data available for different population groups.

3.5

The Government has agreed to carry out two voluntary reviews of progress before 2030. We expected that the first voluntary review would provide a clear picture of progress towards achieving the SDGs and describe the regular reporting arrangements.

Summary of findings

3.6

We could not identify dedicated leadership within central government for the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. In our view, clear leadership would provide greater accountability and momentum for achieving the SDGs and monitoring progress towards achieving them. We also consider that it is important to clearly assign co-ordination and implementation responsibilities to agencies.

3.7

The Government has not yet set out its plan for implementing and monitoring progress towards the SDGs. In our view, this will likely slow progress in implementing the SDGs.

3.8

There have been significant efforts to increase the quality and availability of New Zealand's well-being data. However, a full set of indicators to establish a baseline and regular monitoring for the SDGs is not yet available. Although there is work under way to address data gaps, including data for different population groups, it might come too late to effectively measure progress in meeting the 2030 SDG targets.

3.9

New Zealand's first voluntary review was completed in 2019. The voluntary review highlighted examples of successes and challenges in progressing the SDGs. Although the report refers to some targets that align with an SDG, such as reducing child poverty and greenhouse gas emissions, it does not identify all the SDG targets that New Zealand intends to achieve by 2030 and whether New Zealand is on track to meet them.

3.10

The Government has not established reporting arrangements for the SDGs apart from the two voluntary reviews it has committed to producing before 2030. As a result, there is not a clear picture of progress. However, the Government first needs to identify which SDG targets are important for New Zealand to focus on.

Leadership for sustainable development is not clear

3.11

Many stakeholders we interviewed thought there was a lack of political leadership for implementing the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. They thought Ministerial leadership was needed to signify commitment to, and promote visibility of, the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. At New Zealand's presentation of its first voluntary review to the United Nations in July 2019, the Executive Director for the Sustainable Business Council commented that:

… the New Zealand Government might identify a single Minister to be responsible for the Global Goals in New Zealand, and work with business, the not-for-profit sector, academia and civil society to deliver on our priority areas together.20

3.12

To date, the Government has not appointed a responsible Minister for implementing the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs.21 However, it has indicated that this decision remains under review.

3.13

The 2030 Agenda and the SDGs are far-reaching and interconnected. Therefore, implementing the SDGs requires an integrated approach across agencies, local government, civil society, and academic and private sectors.

3.14

None of the 12 agencies we surveyed thought there was clear leadership for implementing the SDGs (including two that did not know and one that did not answer). Many of the agencies indicated that central government leadership would help their efforts with the SDGs.

3.15

Stakeholders also commented on the need for central government leadership. As well as co-ordinating work on the SDGs across the agencies, they wanted leadership to be "outward facing". This would provide an easily accessible, visible, and central point of contact for local government and non-governmental groups. Strong leadership could raise awareness of the SDGs, facilitate capability building across agencies for implementing the SDGs, and promote the development of good practice guidance within and outside of government. This would help shift perceptions that the SDGs are a reporting obligation to an understanding that they are an opportunity to help address New Zealand's complex social, environmental, and economic issues.

3.16

We agree that there needs to be clear central government leadership for implementing the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. In our view, this would create greater accountability and momentum.

3.17

The people we interviewed suggested several leadership models. The most frequent suggestion was for the Government to give an existing agency a lead co-ordination role. That agency would have the mandate to lead and co-ordinate central government's efforts to achieve the SDGs and facilitate collaboration between the Government and stakeholders.

3.18

Another model proposed would have leadership sitting in one of the new organisational arrangements enabled by the Public Service Act 2020. It was also suggested that non-governmental groups be included, whether in an advisory or reference group capacity or as a more integral part of the co-ordination role. Whatever form that leadership takes, in our view it needs to consider how the Government will work with Māori (see paragraphs 4.10-4.15).

3.19

Some of the stakeholders and agency staff we interviewed commented that, because of the substantial domestic policy components in the SDGs, the lead co-ordinating agency should have a strong domestic focus. It also needs experience in dealing with policy issues that cut across agencies and in working closely with stakeholders.

3.20

In Australia, the co-ordinating role is shared between its Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet for the domestic application of the SDGs and its Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade for the international application.

Responsibilities of individual agencies need to be clarified

3.21

We have not seen evidence of any guidance provided to the agencies on the SDGs or SDG targets that they are expected to implement and measure progress against.

3.22

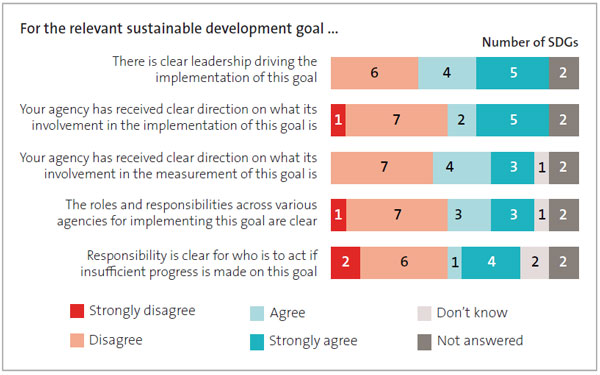

In our survey (see paragraph 1.19), we asked agencies about aspects of the governance and accountability arrangements in place for each of the SDGs. Figure 6 summarises their responses. Clear leadership and accountability are not apparent across the SDGs. For only seven of the 17 SDGs the responding agency had received clear direction on what their implementation and monitoring responsibilities were.

Figure 6

Extent to which agencies agreed or disagreed with leadership and accountability statements for the 17 sustainable development goals

Source: Office of the Auditor-General.

3.23

Roles and responsibilities across agencies were clear for only six of the 17 SDGs. However, many agencies also noted that their work in delivering the Government's policies contributes to specific SDGs. Stakeholders noted that cross-agency efforts to engage with them on the SDGs were not consistent, and they still experienced siloed approaches from agencies.

3.24

Some stakeholders suggested that there should be a lead agency responsible for co-ordinating implementation across relevant agencies and stakeholders for each SDG. This would likely result in greater accountability and improved cross-government engagement with stakeholders, creating more momentum for the SDGs.

| Recommendation 4 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government identify appropriate governance arrangements to implement the sustainable development goals. These arrangements should include assigning clear co-ordination and implementation responsibilities to government agencies. |

There is no consolidated plan for implementing the sustainable development goals and monitoring progress towards achieving them

3.25

The 2030 Agenda does not specify how agencies are to implement the SDGs and monitor progress towards achieving them. Therefore, it is the Government's responsibility to clarify how, and to what extent, the SDGs are to be implemented and progress monitored.

3.26

We acknowledge that there might be plans in place for strategies and initiatives that will contribute to the SDGs. However, we were not provided with any evidence of a national implementation and monitoring plan for the SDGs. We encourage the Government to prepare a consolidated plan to provide a basis for monitoring and to establish reporting arrangements. Without this, progress will be difficult for the Government to track and report, and could be affected. When setting out its plan for implementing the SDGs and monitoring progress towards achieving them, the Government can, and in our view should, identify what can be achieved through existing policies, structures, and monitoring frameworks.

3.27

An effective implementation and monitoring plan for the SDGs would:

- clearly reflect the Government's commitment to the 2030 Agenda and describe which SDG targets New Zealand will work towards meeting;

- describe how relevant plans, legislation, policies, and initiatives are expected to deliver against that commitment;

- identify where gaps remain and what further work is required;

- incorporate, where relevant, good-practice components from other countries' implementation and monitoring plans;

- identify the roles, responsibilities, and actions required to meet New Zealand's commitment for the SDGs overall and for individual SDGs;

- include arrangements for working with Māori and engagement across agencies and with relevant stakeholders, including representatives of vulnerable groups (we discuss stakeholder engagement and communications strategies for the SDGs in Part 4); and

- include clear measurement, monitoring, and reporting direction for agencies to routinely assess progress against New Zealand's SDG targets, particularly progress for vulnerable communities.

| Recommendation 5 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government set out its plan to achieve the sustainable development goals and how it intends to monitor progress. The Government will also need to consider how it will work with Māori and consult with relevant stakeholders when developing the plan. Where possible, the plan should identify what can be achieved through existing policies, structures, and monitoring frameworks. |

Indicators to measure progress towards achieving the sustainable development goals are a work in progress

3.28

The 2030 Agenda states that timely and reliable data is needed to measure progress with the SDGs.

3.29

The Government has made significant efforts to increase its data, monitoring, and reporting arrangements. However, the Government has not confirmed a full set of domestic indicators for the SDGs that would provide baseline data and allow for regular monitoring of progress.

3.30

Some of the global SDG targets might not be relevant to New Zealand. Governments can decide to set their own SDG targets that are relevant to their circumstances. For example, the target to eradicate extreme poverty for all people is currently measured as "people living on less than US $1.25 [estimated NZ $1.75] a day".22 This might not be applicable to New Zealand circumstances, but the target could be replaced with something more relevant.

3.31

Where global indicators only partially address the associated SDG target, more meaningful measures could be identified to use instead. The Government might also choose to revise the targets for 2030 to ensure that they are challenging but still achievable.

3.32

Currently there are two monitoring frameworks that assess well-being in New Zealand:

- Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa – Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand (IANZ), which was developed in 2019 and is led by Statistics New Zealand; and

- a dashboard for the Living Standards Framework, which is led by the Treasury.

3.33

IANZ has about 100 indicators to measure social, environmental, and economic well-being and sustainable development, and is intended to support strategic decision-making.23 It is also the main data source for the Living Standards Framework dashboard, which has 65 indicators, 39 of which are drawn from IANZ. The IANZ indicators were developed after consultation with the public to identify factors important to well-being. There are some indicators that do not yet have data, limiting the extent to which well-being can be measured.

3.34

Statistics New Zealand has mapped 96 of the IANZ indicators to the SDGs. Of these, 27 directly link to one of the 231 global SDG indicators.

3.35

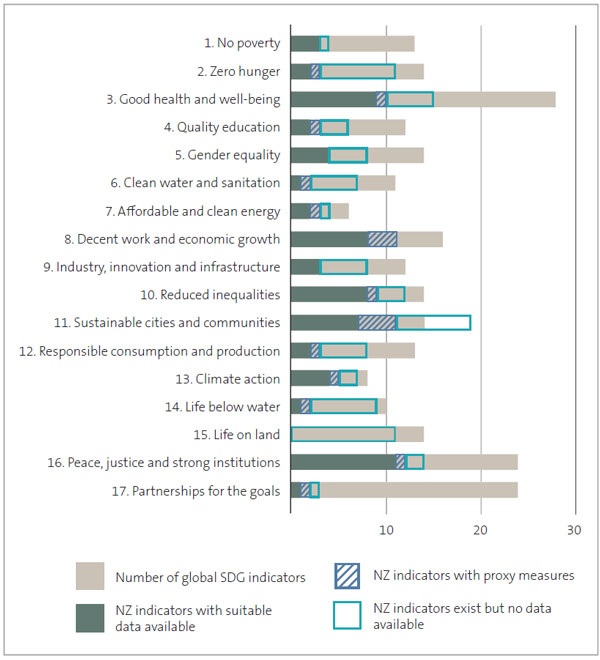

Figure 7 shows the extent to which IANZ currently provides data that can measure progress for each of the 17 SDGs. Of the IANZ indicators mapped to the SDGs, only 49 have suitable data. For 13 indicators, a proxy measure is being used until better data becomes available. The remaining 34 indicators have no data. For example, there is no data yet available for "health equity" (mapped to SDGs 3, 5, and 10), "quality of water resources" (mapped to SDGs 6 and 14), and "harm against children" (mapped to SDG 16).

3.36

In our view, IANZ can provide, at best, only a partial measure of progress towards achieving any SDG. Consequently, we do not currently consider either IANZ or the Living Standards Framework dashboard to yet be adequate to assess progress towards the SDGs.

3.37

The results of our survey of agencies reinforced this. Agencies indicated that work to establish national indicators is complete or nearly complete for only three of the 17 SDGs, although work has started to establish indicators for six other SDGs.

3.38

There have been some international assessments of countries' progress towards the SDGs, including New Zealand, which also provide a partial picture. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has done some reporting of countries' progress towards the SDGs based on the global SDG indicators, most recently in its publication Measuring distance to the SDG targets 2019: An assessment of where OECD countries stand. There was data for New Zealand for 94 of the 169 (56%) SDG targets. Progress on the remaining 44% could not be determined. The international assessments showed similar data gaps in many countries.24

3.39

Reasons for these gaps in the data might be that data collection is challenging, or because they relate to SDG targets that the Government feels are less relevant or lower priority. In our view, it is important for the Government to clarify this.

3.40

The Sustainable Development Report 2021 compared countries on how they were progressing on the SDGs. The report calculated a single index score on which countries were ranked. The index draws on 91 SDG-related indicators. Based on the single index score calculated from this data, New Zealand ranked 23rd out of the 165 countries. However, the report notes that even the top three ranked countries face significant challenges in implementing the SDGs.

Figure 7

Indicators from Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa – Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand mapped to the global indicators for each sustainable development goal

Note: Some of the 231 global SDG indicators and 96 mapped IANZ indicators repeat over some of the 17 SDGs, resulting in a total of 247 global SDG indicators and 157 mapped IANZ indicators in Figure 7 . Goal 11 has more mapped IANZ indicators than global SDG indicators, although many of its mapped indicators do not yet have data. Source: Adapted from the Aligning with Sustainable Development Goals webpage of the Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa – Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand website.

3.41

The Sustainable Development Report 2021 considers New Zealand to have achieved the global targets for SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), but to be facing challenges for the remaining 16 SDGs. For eight SDGs, the challenges are considered significant or major.

3.42

Global progress towards the SDGs is also reported by a number of regional groupings. New Zealand is included in the Pacific region's reporting. In 2017, the Pacific Islands Forum Leaders endorsed 132 sustainable development indicators, of which 127 are drawn from the SDG indicators. The 2018 Pacific SDGs Progress Wheels assessed progress against 80 sustainable development indicators. New Zealand had achieved the target for 10 indicators (12.5%), was making good progress on nine indicators (11%), and was yet to make progress against 19 indicators (24%). New Zealand did not have available data for 42 of these indicators (52.5%), but we note that some of these might include indicators that are not applicable to New Zealand.

Most data cannot be broken down to assess progress for different groups

3.43

The 2030 Agenda states the importance of countries being able to break their data down into different population subgroups. Vulnerable groups can then be identified and their progress tracked to ensure that "no one is left behind" in the nation's sustainable development.

3.44

The 2030 Agenda included the intention that, by 2020, disaggregated data (by income, gender, age, race, ethnicity, migration status, disability, and geographic location) would be readily available to help countries to implement the SDGs.

3.45

Currently, only 33 of the 96 (34%) IANZ indicators mapped to the SDGs provide some form of disaggregated data. Thirty-five of the 65 (54%) Living Standards Framework dashboard indicators have at least one population breakdown, with less disaggregated data available for disabled people and by family type than for gender and ethnicity.

3.46

Some indicators might not be easily disaggregated, or population breakdowns might be less relevant. Low rates of disaggregated data are consistent with agencies' responses to our survey, where work to disaggregate data was nearly or fully complete for only one of the 17 SDGs. Some work had started for only three other SDGs.

3.47

Stakeholders we spoke with reiterated that the vulnerable groups for many of the SDGs are often a combination of demographic groups – for example, older people with disabilities or Māori with lower incomes. The more disaggregated well-being data is, the clearer the links between vulnerability characteristics become, allowing for more targeted policies and initiatives to help ensure that "no one is left behind".

3.48

There might be other sources of disaggregated data available that could be used for sustainable development. As discussed in paragraphs 2.40-2.41, amendments in 2019 to the Local Government Act 2002 reinstated the expectation that councils will promote the four well-beings in their communities by using a sustainable development approach. Taituarā, Local Government Professionals Aotearoa (previously the Society of Local Government Managers, SOLGM) has created a data warehouse that contains disaggregated well-being indicators from more than 30 organisations. Subscribers can use the data to establish baselines of well-being in communities to inform their strategic planning, outcomes setting, and how they measure progress over time.

Efforts to address data gaps need to be accelerated

3.49

There are costs and complexities involved in collecting new data. However, gaps in New Zealand's data systems prevent forming a full picture of well-being, and make tracking progress with achieving the SDGs challenging. The Government's 2019 voluntary review identified the intention to disaggregate data, where possible, in both the IANZ and Living Standards Framework dashboard.

3.50

We were told that, as part of its IANZ work, Statistics New Zealand is working with Te Puni Kōkiri, the Treasury, and other government agencies with an interest in developing te ao Māori indicators. A planned refresh of the Living Standards Framework and its dashboard for 2021 also aims to better incorporate te ao Māori and Pasifika worldviews, child well-being, and cultural indicators. New indicators that result from this work could be relevant for monitoring progress towards achieving SDG targets.

3.51

A whole-of-government data investment plan is being prepared to identify priorities for improving government data, including the investment that might be required to address data gaps in IANZ. Statistics New Zealand, in its role as the Government Chief Data Steward, is leading this work, which includes carrying out a stocktake of essential data assets. However, we were told that the data investment plan has been delayed until late 2021 as agencies prioritise work related to the Covid-19 response. It is not yet known where addressing data gaps related to the SDGs will sit in the prioritisation of New Zealand's data needs.

3.52

In our view, this work needs to be accelerated. At this stage, there is a risk that these efforts might be too late to assess progress with the SDGs and to inform changes in policies and initiatives to help achieve SDG targets.

| Recommendation 6 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government urgently build on the work started with Ngā Tūtohu Aotearoa – Indicators Aotearoa New Zealand and the Living Standards Framework dashboard to ensure that there are appropriate indicators and adequate data to regularly measure progress towards the sustainable development goal targets that New Zealand is aiming to achieve by 2030. The indicators and associated data should be sufficiently disaggregated so they can be used to assess progress for all defined groups, especially those considered the most vulnerable. |

There are lessons to be learned for the next voluntary review

3.53

All countries that committed to the 2030 Agenda also committed to producing at least two voluntary reviews before 2030. By July 2018, all OECD countries except New Zealand and the United States had produced their first voluntary review. New Zealand's first voluntary review (He waka eke noa – Towards a better future, together: New Zealand's progress towards the SDGs 2019), published in 2019, provided a high-level assessment of how the Government's priorities and well-being approach aligned with the 17 SDGs, highlighting examples of successes to date and noting some current challenges.

3.54

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade led the overall co-ordination of this voluntary review and, along with 11 other agencies, drafted one or more of the 17 SDG chapters in the voluntary review. It established a reference group of non-government stakeholders to support the voluntary review. The intention was for the group to be involved from the early stages of writing the report. However, because there was limited time to produce the voluntary review, the group's involvement primarily consisted of reviewing the final draft after Cabinet had signed it off. Despite the tight time frames, the Ministry was able to make the final draft of the voluntary review available online for public feedback.

3.55

For some stakeholders we spoke with, the voluntary review was the Government's first approach to engaging with them about the SDGs. Stakeholders hoped this would lead to ongoing engagement but this has not happened. We discuss stakeholder engagement for the SDGs further in Part 4.

3.56

Of the 12 government agencies involved in drafting the voluntary review, only three (including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade) provided a link to the report on their website. The Ministry was the only agency to also promote the voluntary review through social media.

3.57

Many stakeholders we interviewed commented that the voluntary review reads well. They appreciated a report focused on the SDGs in New Zealand, and were encouraged to see a Māori perspective in a report with an international audience.

3.58

However, a number of stakeholders felt it was not possible to gauge from the voluntary review what SDG targets New Zealand has committed to achieving by 2030, and therefore what progress has actually been made. Some stakeholders questioned the transparency and balance of the reporting. They noted that some chapters provided a more positive picture of progress than The people's report, an alternative review from a group of civil society representatives. Some stakeholders suggested that a government agency with a domestic focus, but that is not responsible for implementing any of the SDGs, should produce the next voluntary review.

3.59

Stakeholders were disappointed at the lack of data in the report to measure progress towards implementing the SDGs. It was initially hoped that the first voluntary review would include performance reporting against a prioritised list of SDG indicators. However, with no prioritised SDG targets, no previous mapping of New Zealand measures to SDGs, and a tight time frame to produce the voluntary review, this was not possible. A link to the IANZ website was provided in the voluntary review, but the data was not presented in a way that allowed readers to gauge progress towards the SDGs. It has been indicated that the second voluntary review will use more data.

3.60

In December 2020, the Associate Minister of Foreign Affairs was delegated responsibility for "Working with the Minister of Foreign Affairs to oversee the preparation and planning of the next Voluntary National Review of the Sustainable Development Goals".25 However, as of May 2021, no review of the first voluntary review had been carried out or was planned, and we were not provided with any information that indicated planning was under way for the next voluntary review.

| Recommendation 7 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Government carry out a review of New Zealand's first Voluntary National Review to identify improvements that can be made for next time, and publicly communicate time frames for the next Voluntary National Review. |

3.61

We are not aware of any reporting arrangements for the SDGs aside from the intention to produce two voluntary reviews. If a reporting framework was established for the SDG targets New Zealand is working towards, this could provide better accountability for SDG-related activities, contribute to a more complete picture of progress alongside descriptive narratives, and enable the Government to take action when it appears targets might be missed.

20: "Abbie Reynolds' remarks to the United Nations" (18 July 2019), Sustainable Business Council, at sbc.org.nz.

21: We note in paragraph 3.60 that the Associate Minister of Foreign Affairs is responsible for working with the Minister of Foreign Affairs to oversee the preparation and planning of the next voluntary review of the SDGs.

22: United Nations (2015), Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, page 19.

23: The IANZ count of 114 indicators is based on 109 unique indicators, five of which appear twice in different domains.

24: Future editions of the Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets reports intend to provide increased data coverage, with the next report planned for early 2022.

25: Schedule of Responsibilities Delegated to Associate Ministers and Parliamentary Under-Secretaries (2020) available from www.dpmc.govt.nz, page 18.