Summary of unappropriated expenditure: 2015/16 to 2021/22

On average, $155 million of government spending in six of the last seven years has lacked proper authority from Parliament. The number of instances has decreased and the value of unappropriated expenditure is a low percentage of the Government’s budget.

This report summarises seven years (2015/16 to 2021/22) of Government expenditure, the level of unappropriated expenditure, and why the expenditure was unappropriated.1

The number of unappropriated expenditure items occurring has decreased, and the value of unappropriated expenditure is a low percentage of the Government’s budget.

Key points

- Although large in amount, the unappropriated expenditure as a percentage of government budget was typically below 0.3% each year from 2015/16 to 2021/22.

- Most causes of unappropriated expenditure were avoidable and administrative in nature.

- Ensuring policy, operational, and finance staff understand both the constitutional importance of appropriations and the requirements to manage them well remains critical.

Our role

As an Officer of Parliament, the Controller and Auditor-General is independent of the Government and is often referred to as the public “watchdog” on government spending. An important part of this role is the Controller function.

Our report Observations from our central government audits: 2021/22 has a detailed explanation on how public expenditure is authorised, who is responsible for managing it, and the Controller’s role in checking.

How much expenditure has been unappropriated?

The Government must not spend public money without Parliament’s authority. This authorisation is provided through an “appropriation” or other legal authority.2 Expenditure incurred outside authority is unlawful.

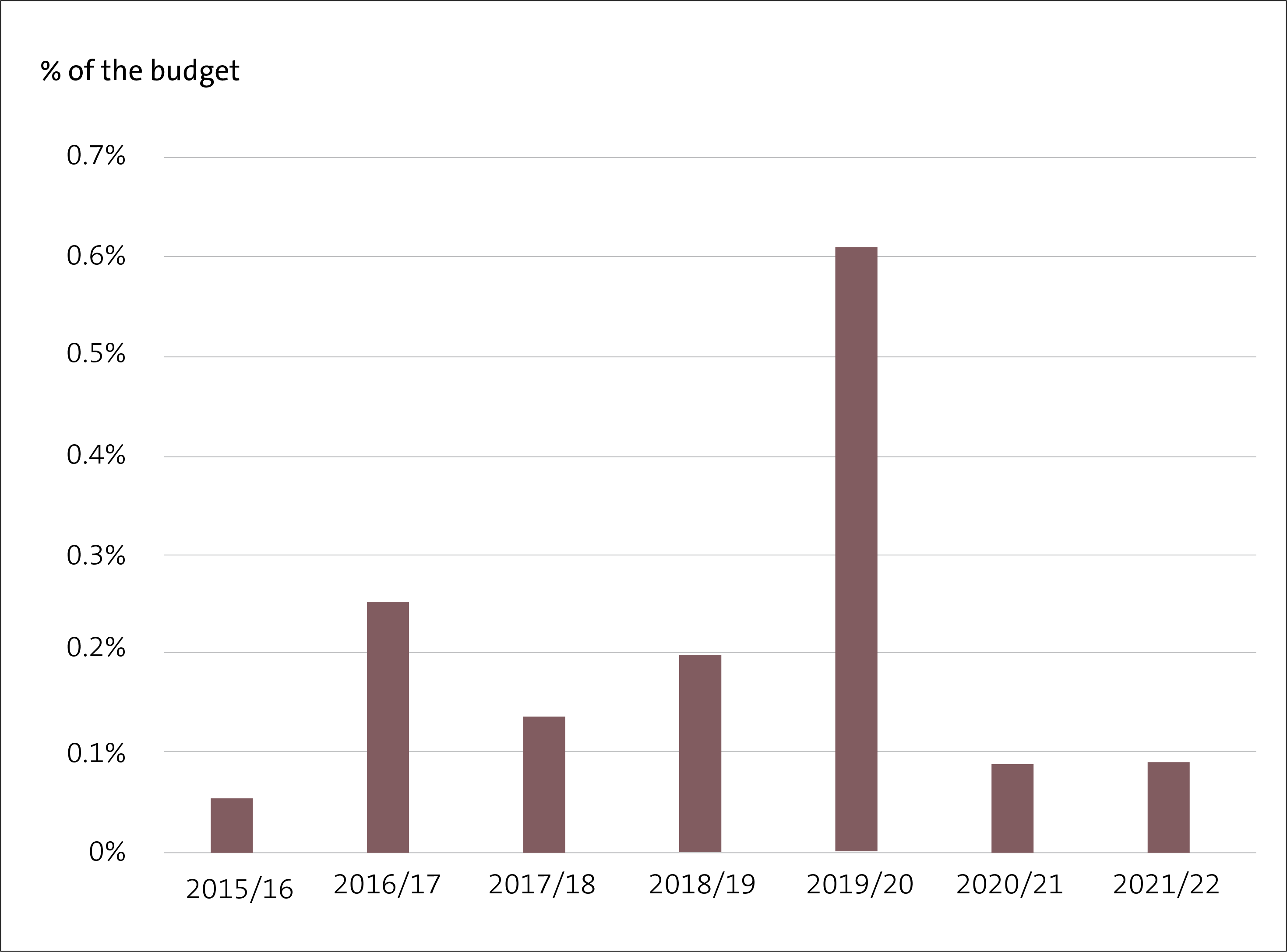

Figure 1 shows that the dollar value of unappropriated expenditure has been below 1% of the budget every year from 2015/16 to 2021/22.3 The percentage is usually around 0.1% to 0.2%.

Figure 1

Total unappropriated expenditure as a percentage of the Government’s Budget, from 2015/16 to 2021/22

The outlier in Figure 1 (0.61%) is 2019/20, the first year of Covid-19. Unappropriated expenditure for 2019/20 was $927 million4 and most of it was from unappropriated expenditure in Vote Revenue ($676.8 million).5 Unappropriated expenditure averaged $155 million each year for the other six years.

We have a strong interest in government departments reducing the instances of public spending without parliamentary authority. Although unappropriated expenditure has been about 0.1% of the budget in recent years, the number of occurrences has decreased. For both 2020/21 and 2021/22, the Government’s financial statements reported 12 occurrences of unappropriated expenditure, which is the lowest number of occurrences this century.6

Why did government departments incur expenditure without appropriate authority?

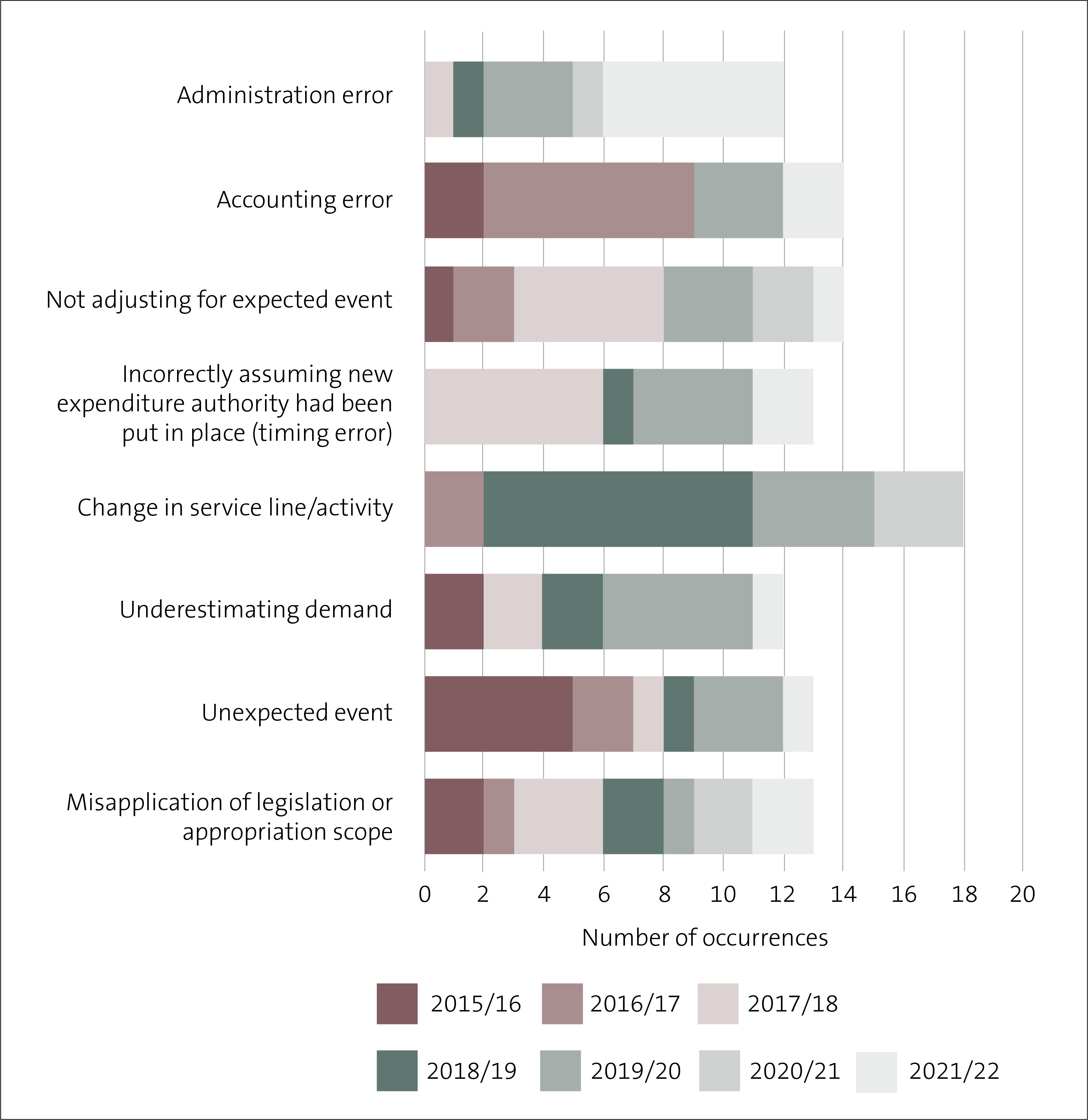

There were various reasons for unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22.7 The most common reason was “Change in service line/activity”, which occurred 18 times. Overall, there were 109 occurrences of unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure, from 2015/16 to 2021/22

We discuss each of the eight causes of unappropriated expenditure below.

Administration error

If the Government wishes to incur expenditure that has not been authorised through the Budget, then it needs authority firstly through an Imprest Supply Act and secondly appropriation through the Supplementary Estimates Act. Some government departments seeking extra, between-Budget spending authority have, in their submission to Cabinet, omitted the wording that expressly requests the use of imprest supply and/or new authority through the supplementary estimates.

More than 83% of administration errors from 2015/16 to 2021/22 occurred in the last three years.

Accounting error

Of the 14 accounting errors that occurred from 2015/16 to 2021/22, the most common is the misclassification of expenditure between capital and operating. There is a greater risk of misclassifying expenditure for large projects. Because government departments tend to have only capital appropriations for capital projects, they can get caught out when generally accepted accounting practice requires the expenditure to be treated as “operating”.

Not adjusting for an expected event

When an event is expected, government departments sometimes fail to consider whether it might result in expenditure and, therefore, have appropriation implications. Government departments can be fortunate if the expenditure falls within an existing appropriation. However, if the event causes expenditure that is not authorised, then unappropriated expenditure will occur. From 2015/16 to 2021/22, unappropriated expenditure in this category occurred 14 times.

Most occurrences of unappropriated expenditure in this category were from government departments incorrectly applying or misunderstanding “in-principle expense transfers” (IPETs). Sometimes Cabinet will agree, in principle, to transfer funding from one year to the next. However, IPETs are not included in the Appropriation Act (the legislation that gives legal effect to the Budget). Therefore, IPETs need Cabinet confirmation in the new financial year (usually in November) and, if confirmed, the related expenditure requires explicit approval to use the imprest supply authority.8

Problems related to IPETs normally involve either:

- government departments incorrectly assuming that granting an IPET is, in itself, the granting of authority to incur expenditure. Consequently, government departments unlawfully incur expenditure before the imprest authority has been given; or

- the IPET is expected to be confirmed (with imprest supply granted) in November. However, the event requiring that authority takes place earlier (that is, between July and November) before the expenditure is given authority.

Incorrectly assuming new expenditure authority had been put in place

Government departments are required to receive approval to spend through imprest supply for additional expenditure during the year. Imprest supply authority is only interim, and the additional expenditure needs to be included in the supplementary estimates before the end of the year.

Some government departments that have incurred expenditure through imprest supply failed to ensure that the expenditure was appropriated when the Imprest Supply Act expired. As a result, unappropriated expenditure occurred at the end of the year.

Conversely, some government departments incurred expenditure without imprest supply authority in the interim, which they believed had been properly sought.

There were 13 occurrences of unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22 in this category, with six in 2017/18.

Changes in service line/activity

Not adjusting for changes in service line/activity was the most common reason for unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22. There were 18 instances of unappropriated expenditure in this category, which was 17% of all instances.

Government departments sometimes make changes to their functions, service lines, activities, or types of expenditure during the year. Some government departments do not pay enough attention to the implications of those changes on the appropriations. Consequently, expenditure can fall outside the amount, scope, or time period of the appropriation.

From 2015/16 to 2021/22, unappropriated expenditure caused by changes in service line or activity has related mainly to:

- advances and loans becoming interest free and therefore incurring an expense that reflects the write-down of their book value;9 and

- legislative changes widening the range of who qualifies for a benefit or other entitlement.

Under-estimating demand

At times, the Government has met increased demand by providing more services to the public than anticipated. The most notable event from 2015/16 to 2021/22 was the Covid-19 pandemic. At the time, it was difficult to forecast how much expenditure would be incurred in some areas. Demand-driven expenditure caused some departments to incur expenditure above the amount of the existing appropriation.

Figure 2 shows that six of the 12 occurrences of unappropriated expenditure from under-estimating demand were from 2019/20.

Demand was also underestimated for the increase in emergency-related costs for disasters and legal services.

Unexpected event

Unexpected events that result in unappropriated expenditure include natural disasters, unanticipated impairments, and unexpected asset transfers. These unexpected events have affected several government departments, resulting in 13 occurrences of unappropriated expenditure.

Natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and storms, occurred many times from 2015/16 to 2021/22. Unexpected expenditure was required to support recovery from these disasters.

Unanticipated impairments were caused by unexpected annual and/or ad-hoc valuations that exceeded the forecasted amount.

Unexpected asset transfers are when an asset is either transferred between government departments or the proceeds of asset sales are kept that were required to be returned to the Crown, which require a capital injection. Government departments often did not consider this in a timely manner, leading to unappropriated expenditure.

Misapplication of legislation or appropriation scope

Misapplication or misinterpretation of appropriation scope contributed to 13 instances of unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22.

Determining which activities fall within the scope of the appropriation, especially during uncertain or extraordinary events like the Covid-19 pandemic, was challenging for some government departments. Quick decisions about the alternative uses of funding in response to the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in some expenditure falling outside the scope of appropriation.

Some appropriation scopes refer directly to primary or secondary legislation. If the legislation is not applied correctly, then expenditure can be outside the legislative mandate and be unappropriated. Further, when amendments are made to such legislation, government departments must ensure that expenditure aligns with any change in the legal criteria. The failure to do so led to several of the 13 instances of unappropriated expenditure in this category.

Lessons learned

The causes of unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22 present an opportunity for government departments to learn from past errors and reduce the amount, number, and frequency of unappropriated expenditure.10

Ways that government departments can help to avoid unappropriated expenditure include:

- ensuring that there is sound knowledge and understanding throughout the government department of the public finance system and appropriation structures, along with the legislative requirements;

- determining when different authorisations are required during the year and how they are correctly sought;

- ensuring that the correct accounting treatments are determined and applied as early as possible, especially for large projects;

- considering the potential implications of any new activities or adjustments to existing activities on accounting treatments and appropriations;

- ensuring that there is sufficient spending authority available for appropriations that cover heavily demand-driven activity;

- taking remedial action quickly when an unexpected event occurs, and unappropriated expenditure is unavoidable, to reduce the amount of time the expenditure is unappropriated;

- ensuring that cost allocation models are updated regularly to record changes to appropriations;

- ensuring that funds spent by third parties are within the scope of appropriations;

- ensuring that, when an appropriation scope is tied to the legislation and that legislation has been amended, practice is immediately aligned to the revised authority;

- being mindful that activities expected to be delivered through new initiatives are allocated against existing appropriations and properly covered by their appropriation scope statements; and

- ensuring that active lines of communication between policy, finance teams, and the Treasury (where relevant) are in place.

1: The Controller is concerned with Government “expenditure”. We sometimes use the term “spending” for readability reasons.

2: Appropriations are authorities from Parliament that specify what the Crown may incur expenditure on (specific areas of expenditure). Most appropriations specify limits in terms of the type of expenditure (such as operating or capital expenditure), what it can be used for, the maximum amount, and the time period.

3: “Budget” refers to the Government’s final budgeted amount, as updated in the Supplementary Estimates.

4: Includes unappropriated expenditure identified after 2019/20 that related to 2019/20.

5: In response to Covid-19’s effect on the economy, Inland Revenue increased the amount of taxpayer debt written off and further impaired the value of taxpayer debt. It sought and gained Cabinet’s approval to increase the relevant appropriation to cover the expense but, in an administrative oversight, did not seek Cabinet’s express approval to use imprest supply in the meantime. Impairments and write-offs totalling $1,356.8 million were therefore incurred against an authority of $680 million, resulting in $676.8 million in unappropriated expenditure.

6: We address the number of occurrences of unappropriated expenditure from 2015/16 to 2021/22 in more detail in Part 3 of Observations from our central government audits: 2021/22.

7: Figure 2 records the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure in each year’s Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand and assigns them to one of the eight categories. However, if the event or act caused unappropriated expenditure across several years, then we have counted it only once. This has also been updated to reflect the most up-to-date information and amendments.

8: An IPET can also get joint-Ministerial confirmation.

9: If loans are provided at lower than market rate, they are “concessionary loans”. As such, the present value of the loan is lower than it would be if it were attracting market rates of interest. When loans become concessionary loans, their book value needs to be written down, and the write-down expense requires appropriation.

10: Includes Offices of Parliament for the purposes of this report.