Part 5: Councils' top risks

5.1

The risks councils face are wide ranging. They include risks related to health and safety, the impacts of climate change, fraud, cyber-security, asset failure, cost escalation, drinking water quality, and changes in regulatory standards.

5.2

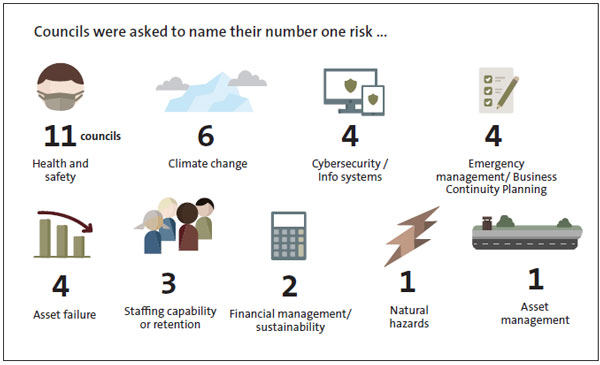

We asked councils what they identified as their top five risks. Of the 56 councils that responded to this question, 11 said that health and safety was their number one risk and six said the impact of climate change was their number one risk (see Figure 8).

Figure 8

The top risks identified by councils were wide-ranging

Note: This is a sample from the responses received from the 56 councils, not a total list.

5.3

In our local government work, we often find instances where poorly managed conflicts of interest and procurement risks reduce the public's trust and confidence in a council. However, not many councils we surveyed listed conflicts of interest or procurement as a top risk.

5.4

We looked at two specific risks – climate change and asset management (including asset failure) – and considered how three councils were looking to mitigate the risks that they had identified.

Climate change

5.5

Six councils in our survey said that their number one risk was responding to climate change impacts. Several other councils included this in their top five risks.

5.6

Climate change poses risks to council activities, and council activities affect the climate. Councils need to:

- advise their elected members of these risks;

- communicate these risks to their communities; and

- make informed decisions about how to manage their assets and deliver services in response to these risks, including assessing options and their cost implications.

5.7

As at February 2020, 17 councils have declared climate emergencies (see Appendix 2). However, in their responses to our survey, some of those councils did not have climate-related risks in their top five risks.

5.8

This might be because those councils are not integrating their climate-related strategy and/or policy decisions into their risk management practices. Another reason might be that councils have incorporated climate change-related risks into other risk categories, such as asset failure.

5.9

If councils are to make well-informed decisions about their climate change work programmes, it is important that they integrate their decision-making and risk management. This also demonstrates to their communities that they are acting on their climate emergency declarations.

5.10

The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures framework has been developed to provide clear and comprehensive information on the impacts of climate change. The framework is structured around four core categories, one of which is risk management. Councils are encouraged to become familiar with the framework.9

5.11

In Figure 9, we describe Queenstown-Lakes District Council's approach to embedding a consideration of climate change risks into its current and future risk context.

Figure 9

Queenstown-Lakes District Council's approach to embedding a consideration of climate change risks in its risk context

| Queenstown-Lakes District Council has taken steps to embed climate change into its current and future risk context. The Council identified ineffective planning for climate change as one of its top five risks. The Council adopted a climate action plan after consulting with its community, holding workshops, and commissioning scientific research on climate change impacts and implications for the district until the end of the century. The climate action plan has the following five key outcomes:

Actions under the climate action plan to date include forming a Climate Reference Group and developing a draft Emissions Reduction Masterplan and Sequestration Plan for the district. The plan notes that the Council will develop a performance framework and identify key performance indicators. The Council considers that there is good engagement with the climate action plan and strong community support, both in terms of adapting to climate change effects and reducing emissions. The Council aspires to have net zero carbon emissions in communities in the district as part of its Vision 2050 strategy. Council officers report on progress in implementing the Council's climate action plan as a standing item in the Audit Finance and Risk Committee agenda and identify areas for further investment and action. The reports update the committee on progress in achieving the five outcomes, actions in the plan, priorities for the next quarter, actions that have been delayed or rescheduled, risk mitigations, and updates on changes in the operating environment (such as the Climate Change Commission's advice). |

Asset management

5.12

Many councils' top risks relate to asset management. Councils are responsible for managing assets with a combined value of more than $160 billion. Councils deliver core services to their communities through these assets. Councils are accountable for the decisions they make about how these assets are managed.

5.13

Climate change, natural hazards, growth, increasing environmental and health standards, regulatory change, understanding the condition of existing infrastructure, and funding constraints all affect whether councils achieve their asset management and service delivery objectives.

5.14

Many assets are also coming to the end of their useful life, and performance issues might arise as a result. We have previously highlighted concerns that councils might not be sufficiently reinvesting in their critical infrastructure assets. This is based on planned renewals expenditure being less than the forecast depreciation charge.10

5.15

Recently, as part of their 2021-31 long-term plan consultation, several councils identified that they have been underinvesting in their assets.11 Some communities are already experiencing asset failures because of this underinvestment.

5.16

To manage infrastructure assets, councils need to have reliable information about the condition and performance of their assets. Reliable asset information is important for mature asset risk management.

5.17

However, many councils struggle with getting reliable asset information, despite the benefits. In Figure 10, we describe Waimakariri District Council's approach to managing its assets.

5.18

To govern the management of assets effectively, elected members should ask questions and/or receive information (preferably trend information) about the following:

- What is the knowledge we have about our assets?

- What percent of our assets have been inspected and when?

- How are we monitoring the performance of our assets?

- What are the asset failure trends?

- What do we spend on reactive versus planned maintenance versus relevant benchmarks?

- Does our future investment programme adequately consider risk and allow the council to take a risk informed investment approach?

Figure 10

Waimakariri District Council's asset planning and information

| Waimakariri District Council recognises that good asset planning and information helps manage risks at a strategic level and when it responds to an immediate issue, such as the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010 and 2011. When the earthquakes happened, the state of its assets held few surprises for the Council. Within days of the earthquakes, the Council was able to make significant decisions about replacing pipes to restore assets and accommodate the required future growth in the district. For many years, the Council has prioritised its understanding of what assets it owns, where those assets are located, hazards that might affect its assets, and where there is capacity for growth – including population, demographic, and industry changes. The Council has collected all of the important information for reticulation pipes, such as pipe diameter, ground conditions, and how deep the assets are. The Council has assessed vulnerable and critical assets, and it has plans in place to renew these assets before they fail. The Council has taken a long-term view in preparing its infrastructure strategy. As a result, it has ring-fenced the money it needs for its asset renewals. The Council has also costed the likely impact of another natural disaster and has sufficient "head room" in its financial strategy to respond to such an event. There is a strong commitment to resourcing for both staff and technology. The Council actively recruits interns and graduate engineers and provides them with training. This supports a sustainable workforce. The Council reviews its risk register quarterly and reports a reasonable level of detail. The Council has recognised that it needs to improve its reporting to elected members, noting that reporting often influences the desired change. The Council currently provides detailed asset management plans and reports compliance on performance measures and the capital works programme to its elected members. However, this does not report on service level outcomes, and the Council has noted that this is a matter it could report on. |

5.19

We have reported that many councils plan to invest in their assets at significantly increased levels. However, they have struggled to achieve their capital expenditure programmes.12

5.20

Project delays or deferrals are typically the most common reasons councils give for spending significantly below their capital expenditure budgets. These delays can be caused by re-prioritising council projects, internal delays (such as consenting issues), and contractual delays (such as tender processes taking longer than expected). These risks are often not well described or understood when capital programmes are approved.

5.21

In Figure 11, we describe Waipā District Council's approach to managing the risk of not delivering its capital works programme.

Figure 11

Waipā District Council's approach to managing the risk of not delivering its capital works programme

| Waipā District Council staff told us that the Council's most pressing risk is how to deliver its capital works programme to provide the infrastructure to support expected high levels of growth. The Council continually reviews project risks and assigns these to "owners" where appropriate. Project managers identify risks at a project level, but the owner of the work programme is expected to consolidate risks at a programme level. This enables cross-organisation responses to be prepared. Risks filter down through the Council's business planning process and are reported to the audit and risk committee quarterly. The key purpose of the report is to provide a base for discussion and start effective risk conversations by the committee. The report provides the committee with the results of the quarterly review of risks, an update on the status of the mitigation measures, and an update on the implementation of the risk management strategy. The executive also carries out a quarterly review of the report in the lead-in to the audit and risk committee review. |

5.22

Councils need to deliver large and complex capital programmes. This was reinforced in councils' 2021-31 long-term plans, where capital expenditure forecasts continue to significantly increase over long-term plans.

5.23

We consider that, given the complexity of decisions that councils need to make about large infrastructure projects, they could make more use of specialised risk management techniques. We have seen limited use of such techniques by councils.

5.24

Quantitative risk analysis or assessments can assist councils in decision-making by providing a probability associated with particular outcomes. This would enable councils to understand what controls or interventions are likely to have the greatest effect on reducing risk.

5.25

Councils cannot make strategic decisions if they do not know where their risks are and what effect they have.

| Recommendation 3 |

|---|

| We recommend that councils consider using more sophisticated techniques for identifying and managing risks on key programmes of work, such as quantitative risk assessments, given that the assessments that many councils make, particularly on the delivery of their capital expenditure programmes, need a high level of judgement. |

The failure of important relationships is a strategic risk

5.26

Councils depend on successful relationships to achieve their strategic objectives – including relationships with neighbouring councils, central government, mana whenua, and their council-controlled organisations.

5.27

We saw councils recognising the failure of key relationships as a strategic risk. In Figure 12, we describe Auckland Council's identification of its inability to achieve Māori outcomes as a top risk.

Figure 12

Auckland Council – achieving Māori outcomes

| In May 2020, Auckland Council identified its inability to achieve Māori outcomes because of Covid-19 as a top risk. The Council noted that Covid-19 was expected to have serious and prolonged effects on all vulnerable communities. There was a potential risk that the Council might be unable to meet its responsibilities to Māori, which would have a range of significant impacts and consequences. Risks have been defined in three related parts as the risk of:

|

9: Matt Raeburn and Rick Lomax (July 2021), "TCFD framework and climate change obligations", Local Government Magazine New Zealand, pages 40-42.

10: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Insights into local government: 2019, paragraph 1.10.

11: For example, see Central Hawke's Bay District Council (2021), Facing the Facts: Consultation Document Long Term Plan 2021-2031, page 2.

12: Office of the Auditor-General (2020), Insights into local government: 2019 page 13, and Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans, pages 19-20.