Part 3: Capital expenditure trends

3.1

In this Part, we discuss the capital expenditure trends in the 12 port companies. We cover:

- the amount of investment the port companies made in their assets;

- the importance of having a good business case to support decisions about capital expenditure;

- Lyttelton Port Company's investment story; and

- the risk of over-investment in port companies.

3.2

Capital expenditure is generally defined as the money that an organisation spends to buy, update, or improve long-term or fixed assets, such as property, plant, buildings, technology, or equipment. This type of spending is intended to increase the capability or capacity of the organisation's operations or add some economic benefit to its operations beyond the current year.

3.3

For this Part, we have characterised purchases of property, plant, and equipment, investment property, and intangible assets as capital expenditure.

Port companies continue to invest in their assets

3.4

In the last five years, port companies have invested about $2 billion in their assets. One of the main reasons that all port companies have invested in their assets is because the ships visiting New Zealand's ports are getting larger.

3.5

This is a trend that has gone on for many years. Since 2014, the percentage of ships visiting New Zealand that can carry between 4000 and 6000 containers18 has increased from 34% to 62%. At the same time, the percentage of smaller ships (that is, ships carrying fewer than 4000 containers) visiting New Zealand ports has declined significantly.

3.6

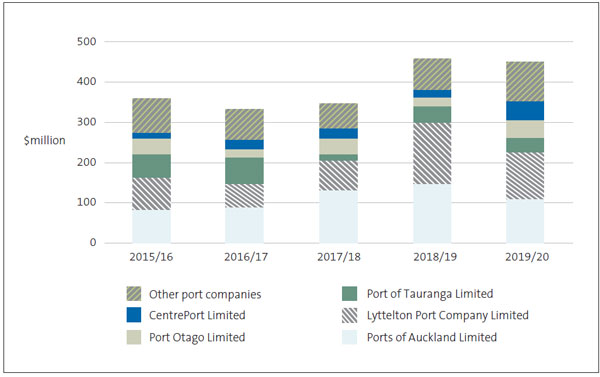

Most of the capital expenditure of the port companies has been by a few companies (see Figure 4). Ports of Auckland and Lyttelton Port Company have spent more than half of the capital expenditure incurred by port companies in the last five years.

3.7

These port companies' capital expenditure has been for business transformation purposes and, for Lyttelton Port Company, to repair assets damaged by the 2010 and 2011 Canterbury earthquakes.

3.8

Lyttelton Port Company had to rebuild its port after the 2010 and 2011 Canterbury earthquakes. This rebuild led to a wider expansion project. We discuss Lyttelton Port Company in paragraphs 3.18-3.27.

3.9

Ports of Auckland has been working on improving its productivity by automating certain operations (for example, purchasing a fleet of new autonomous straddle carriers) and investing in its freight hubs.19 Automating port operations is a trend we have seen in other port companies. However, they have also invested in complementary areas, such as inland ports and commercial property.

Figure 4

Capital expenditure incurred by port companies, 2015/16 to 2019/20

Source: The port companies' annual reports.

We expect port companies' investment in their assets to remain significant

3.10

Port companies' investment in their assets is likely to remain significant during the next few years. Although Ports of Auckland and Lyttelton Port Company are coming to the end of their current investment programme, other port companies are starting theirs.

3.11

For example, CentrePort's port assets were significantly damaged by the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake. As described in paragraph 2.15, CentrePort finalised its insurance settlement in 2019/20. CentrePort has recently announced a port redevelopment and regeneration plan, which it plans to use the insurance money for. Completing this port redevelopment could take more than 10 years.

3.12

Port of Napier has begun constructing a new multi-purpose wharf. This is intended to increase capacity to meet additional shipping demand and improve supply chain efficiency. This investment is expected to cost Port of Napier between $173 million and $190 million and is expected to be completed in late 2022.20

3.13

As well as investing in new assets, all port companies will need to continue to reinvest in assets that are reaching the end of their useful lives.

The importance of good business cases to support capital expenditure decisions

3.14

In the 2018 letter we wrote to chief executives and chairpersons of port companies, we noted that it was difficult to form a view about whether the capital expenditure of port companies was a good use of shareholders' funds.21 This was because of the different approaches port companies used to measure the value of their property, plant, and equipment (we discussed this in paragraphs 2.26-2.31).

3.15

Our view has not changed. We expect port companies making significant investment decisions to prepare a robust business case that outlines the risks and opportunities of the investment decision. We also expect senior management, the board, and, as applicable, the shareholders to approve the business case before the investment goes ahead.

3.16

Given how the increased uncertainty from Covid-19 is affecting the wider freight logistics sector, business cases should actively consider and reflect that uncertainty.

3.17

Although reporting progress against their business cases might be considered commercially sensitive, port companies should look at ways to describe their progress so their shareholders can understand how their investments are being managed.

Lyttelton Port Company Limited

3.18

As outlined in paragraph 2.11, Lyttelton Port Company wrote down the value of its assets by $190.5 million in 2019/20. This followed a write-down of its assets by about $100 million in 2015/16. Together, these asset write-downs represent a significant loss in shareholder value.

3.19

The 22 February 2011 earthquake was centred not far from the Lyttelton port. The earthquake caused extensive damage to the port's wharves and infrastructure. However, it remained open and processed record volumes of containers, coal, and log exports while carrying out repairs. Lyttelton Port Company was insured and received insurance revenue of $438.3 million from its insurance claim.

3.20

Lyttelton Port Company's board and management identified that the completed repairs could not be permanent and that it would be necessary to rebuild a large amount of the port. This led to the board reviewing the future of the Lyttelton port.

3.21

The outcome of that review was the Lyttelton Port Recovery Plan, which was published in November 2015. The recovery plan was intended to provide a "road map" for the port's redevelopment.

3.22

It was estimated that the plan would cost about $1 billion to implement. At its core, the plan was based on three objectives:

- replace damaged port assets with modern, fit-for-purpose infrastructure needed for the safe, effective, and efficient operation of the port;

- reconfigure the port to improve efficiency and enable it to meet current and predicted future shipping and logistical demand; and

- increase the resilience of the port and the greater Christchurch community more generally.

3.23

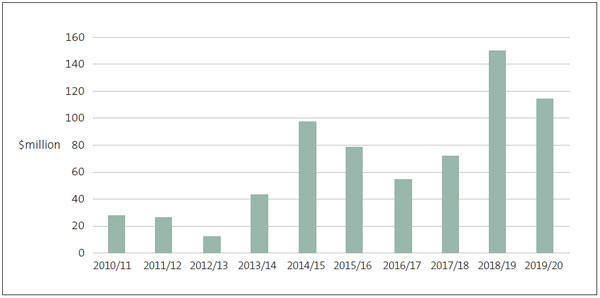

Figure 5 shows Lyttelton Port Company's capital expenditure since 2010/11. In total, it has spent $680 million to date, with the largest capital expenditure in 2018/19 and 2019/20. For context, in 2010/11, Lyttelton Port Company recorded a value for its property, plant, and equipment of $201 million. During the 10-year period to 2019/20, Lyttelton Port Company's revenue from its port operations increased by 41% (excluding insurance revenue received).

Figure 5

Lyttelton Port Company Limited's capital expenditure, 2010/11 to 2019/20

Source: Lyttelton Port Company's annual reports.

3.24

Financial reporting standards require Lyttelton Port Company to ensure that the carrying value of its assets does not exceed the value of the future cash flows the assets are expected to generate.22

3.25

If an organisation cannot generate the future cash flows to cover the cost of the assets constructed or purchased, NZ IAS 36: Impairment of Assets requires the organisation to reduce the value of the asset to what the asset's future cash flows can support.

3.26

The board wrote down the value of its assets by $290 million because:

- the expected growth in volumes did not occur;

- the company was unable to increase its prices enough to cover the cost of the new investment; and

- although some of the assets built by the port company are expected to provide wider community benefits, they will not provide the financial return it desired.

3.27

In discussing the asset write-down in its 2019/20 annual report, Lyttelton Port Company stated:

This readjustment recognises that our asset value and our ability to generate earnings in the current environment are out of line. It brings LPC's value back in line to reflect how much we can actually earn from our assets.23

The risk of over-investment by port companies

3.28

One risk that we see when looking at port companies and their plans to reinvest in their businesses is excess investment or "stranded or underperforming assets".

3.29

New Zealand is a small country with a proportionately large number of ports. It is not feasible for every port to cater for the larger ships that transport the country's imports and exports. Although not every port company is planning to do this, several are.

3.30

New Zealand's economy can generate only so many ship and freight movements, and expectations about the future rates of growth in freight are variable. Given this uncertainty, port companies planning to invest to meet that growth should be realistic about how much growth they assume. The example of Lyttelton Port Company illustrates the loss of shareholder value that can come from investing for growth that does not occur.

3.31

Because of the relative proximity of ports, there is considerable competition between them. The push to increase revenue streams and profits has led some port companies to invest outside of their traditional locations to obtain increased cargo volumes. For example, Port of Tauranga set up inland ports24 in Auckland and Canterbury, and Ports of Auckland set up freight hubs in the Bay of Plenty and Waikato regions.

3.32

Ports are public assets and are majority owned by councils or community interests. Therefore, there is a significant risk that, without a level of national co-ordination, the collective investment of the port sector will not generate the returns anticipated.

3.33

In our view, the lack of a comprehensive supply chain strategy for the wider freight logistics sector heightens the risk of excess investment by port companies.

3.34

Our reference to a comprehensive supply chain strategy deliberately refers to the freight logistics sector instead of the port sector. Port companies are one part of the freight logistics sector and cannot be considered in isolation.

3.35

A comprehensive supply chain strategy could consider what level of investment port companies will need in the future to respond to the effects of climate change and new technologies for supply chains.

3.36

The Ministry of Transport indicated in its briefing to the incoming minister that it is considering preparing a supply chain strategy for New Zealand. The Ministry recently received approval from the Minister of Transport to initiate a freight and supply chain strategy in the second half of 2021, with the intention of delivering the strategy in the next 12-18 months. We support this initiative and encourage the Ministry to include the above elements in its strategy.

18: The industry refers to a standard size for shipping containers as the "twenty-foot equivalent unit". This is based on the dimensions of a standard container – height 2.59 metres, width 2.44 metres, and length 6.10 metres.

19: We describe "freight hubs" in paragraphs 5.13 and 5.15.

20: These values exclude interest costs and applicable overheads.

21: See Port companies: Matters arising from our 2016/17 audits, dated 19 June 2018, on our website, oag.parliament.nz .

22: The relevant accounting standard is New Zealand Equivalent to International Accounting Standard 36: Impairment of Assets.

23: Lyttelton Port Company Limited (2020), Leading the way: Annual report 2020, page 4.

24: We describe "inland ports" in paragraphs 5.12 and 5.15.