Chapter 3: People's experiences of the 'family violence service system'

3.1 Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the literature about people’s experiences of the ‘family violence service system’, focusing on access and engagement with services and how services met their needs. We identify key themes emerging from studies about what people find supportive and beneficial, and conversely what are the barriers to service engagement and areas services can improve on.

Challenges and limitations

Presenting an overview of studies on people’s experiences of the ‘family violence system’, even with a focus on the ‘service system’ is challenging for several reasons. As stated earlier, there is no one ‘family violence system’, as the concept very much depends on the perspectives of who is drawing the boundaries about what is, and is not, included in a system.

The literature is differentiated into specialist areas making it challenging to draw conclusions that are valid across all areas. Research and evaluation studies tend to focus on certain populations within the context of different types of family violence. For example, women who have been victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), men who use violence against their partners/ex-partners, children who have been referred for care and protection concerns, victims of sexual abuse. This may be further differentiated by type of populations, such as Māori whānau, Pacific peoples, people with disabilities, older people and LGBTQIA+.

Studies usually focus on services users’ short-term experiences of a service or programme to evaluate implementation and effectiveness in specific locations. Some exceptions to this are studies that focus on people’s experiences of a set of services, for example justice related agencies and services involved in interagency initiatives. There are very few studies that take a longer-term approach that follow people’s journey through ‘the system’ and examine the complexity of what contributes towards healing and positive changes.

Research and evaluation studies often do recognise the influence of local contexts in their design with the inclusion of different types of geographical and demographic populations. For example, some of the barriers to accessing services are related to the availability of specialist services in an area, travel distances and costs, privacy concerns in small communities and so forth. However, the way research and evaluation studies are commissioned suggests there has been limited systematic monitoring and evaluating people’s experiences and outcomes and ensuring that different populations and types of violence are examined over time and in different locations. This would better inform service commissioning and funding of different types of services and at different locations.

Giving voice to experiences of different population groups

To organise this diverse literature, we have used population groupings to ensure that we give voice to the experiences of those who are often missed in a generalist summary. Firstly, we focus on general themes and examples from a whole of population perspective. Secondly, we examine findings for Māori whānau. Thirdly, we examine the experiences of other population-based groups, including Pacific peoples, ethnic communities, older people, people with disabilities and LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community.

It is important to be mindful that diversity exists within these population-based groups as well as people identifying with multiple groups. Carswell, Donovan and Pimm (2018)28 note that one risk of categorising people into sub-populations is the potential perception of homogeneity, which could lead to service providers expecting to be able to provide a generalised service to all members of that group. Wharewera-Mika and McPhillips (2016) emphasise that services need to be delivered in a culturally competent way. However, this does not mean treating all members of a culture in the same way. ‘Rather, it presumes that difference and diversity between and within groups are valued, and acknowledges a positive integration of diversity, difference and multiculturalism within a system of care’ (Wharewera-Mika & McPhillips, 2016, p. 42).

Indeed:

… identities are complex intersections of multiple elements (sex and gender, ethnicities, religious beliefs, socio-economic status, age, abilities, education etc) and … the lived experiences of people are far more complex and need service responses that can identify and understand different needs, be flexible, client-centred, and respectful. (Carswell, Donovan & Kaiwai, 2019, p. 19).

3.2 Needs of families and whānau affected by violence

A crucial theme relates to the diversity of people’s needs and that they require different supports at different times. The repeated nature of this type of violence means the journey from crisis to recovery for victims is seldom straightforward as perpetrators can use a range of abusive behaviours over time to control and coerce their victims. As previously stated, exposure to prolonged trauma has an accumulative effect on victims which can cause a complex range of physical, psychological and socio-economic issues.

At times of crisis, safety is the major concern for victims (adults and children) along with ensuring that they have access to services to meet any health, safety and practical needs. For victims of IPV, their short-term needs may include support with protection orders and legal matters; developing safety plans; access to safe housing and home security measures; access to income; and ensuring children can safely access school and so forth. Longer-term needs focus on rebuilding their and their children’s lives and meeting needs for health, education, income, stable housing, skills development and building social support networks. The impact of violence can cause severe psychological distress resulting in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and associated symptoms of anxiety and depression that require trauma-informed counselling.

Similarly, the needs of perpetrators of violence vary, and must be considered within the context of keeping victims safe and the risk of perpetrators committing further abuse. Perpetrators require tailored support to take responsibility for their actions and to change their attitudes and behaviours to choose not to use violence. Studies have identified perpetrators may also have practical needs related to housing and income, and therapeutic needs related to mental health, addictions, and individual counselling to address historic trauma.

Although many studies identify the needs of specific populations, only one study attempted a more systematic approach to provide an overview of family violence service users’ needs. Allen and Clarke’s (2017b) research asked 20 service providers throughout Aotearoa New Zealand to record the needs of their clients over a fortnight using a standardised form. A diverse range of services participated including mainstream family violence services, kaupapa Māori providers, organisations providing services for children and young people, male victims, female perpetrators and older populations. The sample included the following:

- Information was collected for a total of 380 clients.

- Ethnicity was reported as 34% Māori, 8% Pacific peoples, 56% Pākehā/European, and 5% Asian.

- 83% of clients were aged 20 years or over.

- Just over half of the sample were female victims, and 5% were male victims.

- 28% were male perpetrators, and 3% were female perpetrators.

- Clients who were both victims and perpetrators were 6% female and 8% male.

- Of the total sample, 43% were identified by providers as being low risk, 39% as medium risk and 15% as high risk.

Unsurprisingly, the research found that the needs of victims and perpetrators were different, with the top needs for:

… victims being more focussed on safety and addressing trauma (e.g., counselling, mental health services, police safety orders and protection orders, and legal advice/assistance), whereas the top needs for perpetrators were focussed more on the development of skills (e.g., relationship, parenting, and non-violence skills). Needs for family and whānau support and for AOD services were also more common for perpetrators. . . . Clients who were identified as being both a victim and a perpetrator had needs that looked similar to the needs of perpetrators, but with a greater need for crisis and supportive counselling. (Allen and Clarke 2017b, p. 36.)

The study found that the level of support for victims and perpetrators to access services and navigate the system was not just determined by risk level or by whether a case has complex multiple needs. High-risk clients with multiple needs requiring support to navigate the system were identified, as were a large proportion of low-risk clients and large numbers of clients whose needs were identified as ‘straightforward’. The authors recommend, ‘This highlights the importance of providing navigation and support services based on the unique needs of individuals, rather than pre-determining provision of this support based on risk or perceived complexity of need’ (Allen and Clarke 2017b, p. 40).

3.3 Enablers and barriers to accessing and engaging with services

3.3.1 Frameworks for conceptualising service access and engagement

The previous section identified that a wide range of services are required to support the needs of family and whānau effected by violence. This includes specialist services and generalist services (Rudman et al., 2017). The historical development of services related to family violence (primarily IPV), sexual violence and child protection is still largely reflected in separate responses from government and community organisations. The experiences of families and whānau are very much dependent on reporting pathways (Polaschek, 2016; Allen & Clarke, 2017b) and whether legal and statutory obligations are activated, as is certain funding arrangements providing free access to services (e.g. protection orders provide access to free Ministry of Justice-funded safety programmes, non-violence programmes and children’s programmes).

Most people experiencing or using violence do not access services. The NZCVS Topical Report: An overview of important findings (Ministry of Justice, 2019a, p.19) found that most family violence victims (more than 90%) are aware of support organisations but that only about a quarter (23%) of those aware of the support organisations contacted them. An important finding is that more than half of family violence victims asked for help from family, whānau or friends. This strengthens calls for more resourcing of prevention and early intervention initiatives to support informal networks of family, friends and work colleagues to know how to safely ‘recognise, respond and refer’ to requests for help (Ministry of Justice, 2020a). Although this chapter focuses on service access and support, the importance of informal networks to prevent further violence and support people long after the services have left requires more focus, including how services can assist people to strengthen positive support networks.

The NZCVS Topical Report – Offences against New Zealand adults by family members (Ministry of Justice, 2020b) found the following about victims’ service access and use:

- 15% said they had received medical attention.

- One in three (32%) said they had an incident that became known to the Police. Victims of offences by an intimate partner (45%) were twice as likely to have an incident reported to the Police than victims of offences by another family member (20%).

- One-third (32%) said they had contacted or were contacted by a family violence support service.

- More than half (51%) said they had asked for help from family, whānau or friends. (Ministry of Justice, 2020b)

For children, their ability to get support and access services is further reduced, and research has shown that, when they do tell someone, they are not always believed or receive the support they require to keep them safe and ensure their wellbeing (e.g. Herbert & Mackenzie, 2018b; Carswell Kaiwai, Moana-o-Hinerangi, Lennan, & Paulin, 2017).

Concepts of service access

Understanding the enablers and barriers to getting the supports people need to address family violence, sexual violence and child abuse and neglect, at the time they need them, requires an understanding of interactions within a ‘family violence service system’ between structural factors, government agencies and service providers and individuals/families/whānau requiring supports.

The findings on what enables people’s access and engagement with services can be conceptualised using a broader definition of ‘access’. A review of the health literature by Levesque et al. (2013)29 identified a range of views about the concept of access to services in terms of attributes, focus and scope. ‘Access’ has been conceived with a narrow focus on the process of seeking service support to initiation of service provision. An intermediate view takes the concept further beyond first contact with a provider to the ongoing care aspects of health care. A broader perception of ‘access’ includes aspects such as ‘trust in and expectations towards the health care system, health literacy, knowledge about services and their usefulness’ (Levesque et al., 2013, p. 9).

A more comprehensive concept of ‘access’ would consider factors pertaining to the structural features of the health care system (e.g. availability), features of individuals (consisting of predisposing and enabling factors) and process factors (which describe the ways in which access is realised) and pertains to dimensions of availability, accessibility, accommodation, affordability and acceptability (Carswell, Donovan, Pimm, 2018).

The framework below identifies key factors that can act as either enablers or barriers to accessing and engaging with government agencies and family violence/sexual violence and child protection services.

Table 4: Dimensions of ‘access’ to family violence/sexual violence and child protection services30

| Access dimensions | Factors that act as enablers or barriers to service access and engagement | |

|---|---|---|

| Barriers | Enablers | |

| Approachability | Victims entrapped/monitored by perpetrator Unable to get a referral, delays in being able to access services due to inefficient referral systems Reluctant to approach service due to hearing reports of others’ bad experiences of a service Stigma and shame associated with contacting FV/SV services Lack of awareness of services – ‘you don’t know what you don’t know’ Not understanding the language |

Outreach by service providers Ability to self-refer to services Ensuring institutions maintain accurate ethnicity and up-to-date contact details to facilitate referrals to appropriate service providers Developing a reputation for being culturally competent in every way – e.g. ethnicities, sexuality, gender identities, etc. Discreet signage, welcoming friendly approach, peer support, hope for recovery Promotion about what a service can offer; justice system staff ensuring people are informed about services and their rights to access such services Providing translators for those with limited proficiency in English; information is in plain English i.e. clear and concise, avoiding complex vocabulary and jargon |

| Acceptability | Previous experience of unhelpful service providers, discrimination, racism, bias, being judged, etc. Feeling more vulnerable and scared at thought of asking an organisation for help than of experiencing IPV. Consequences of seeking help prevent victims from reporting e.g. repercussions from perpetrator; fears children will be taken into state care Negative perceptions of service safety, privacy, and confidentiality |

Readiness to seek support Knowledge about what a service can offer Good reputation of service ‘word of mouth’ Positive perceptions of service safety, privacy and confidentiality Cultural acceptability – cultural safety and comfort level going to service Inclusivity – positive perceptions of how the service relates to you and meets your needs Culturally competent staff Improve safety and quality of services to ensure clients feel safe and comfortable in a supportive, non-judgemental environment |

| Availability | Strict eligibility criteria that restrict who can access the service Confronted with delays and waiting lists when finally reaching out for help No services nearby, availability in rural areas Restrictive opening hours e.g. working hours only, so unable to get there |

Services being open and welcoming to all who need them Services available when needed, courage required to ask for help is acknowledged Outreach services, marae-based services; coordinated service delivery in urban and rural areas Flexible opening times, including evenings and weekends |

| Affordability | Charges for services are not affordable In-direct costs such as travel expenses and childcare |

Services are free of charge Indirect costs are addressed e.g. offer petrol vouchers, childcare facilities, etc |

‘Fit’ between service providers and service users

The ability of service providers and the family violence system to engage with different people requires capabilities, capacity, and flexibility to ‘fit’ with them and provide a service that enables equitable access (Foote et al., 2016).31 Research identified the importance of the relational approach of workers to engage clients who were deemed ‘hard to reach’ within the context of a supportive service system, to ‘make services reachable’.

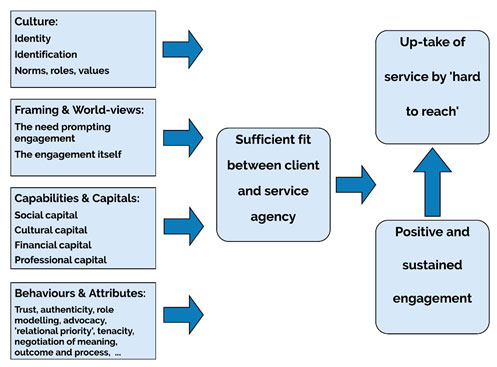

Diagram 1: Elements influencing ‘sufficient fit’ between provider and individual leading to up-take of services developed by Foote et al. (2016)

3.3.2 Barriers to service access and engagement

Studies commonly refer to the following barriers to people accessing services:

Victims entrapped and monitored by perpetrators

- Any analysis of access to services for adult victims of family violence, sexual violence and child abuse victims requires an understanding of both the nuances of entrapment and monitoring by the perpetrator and the dangers of seeking help (Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2020; Ministry of Social Development, 2019a; Wilson et al., 2019; Carswell et al., 2017; Roguski, 2013; Boutros et al., 2011; Davey & McKendry, 2011; Levine & Benkert, 2011).

- Reticence to proactively seek help, often in times of crisis, can be from a fear of encountering institutional indifference, and unhelpful and dismissive people who should be helping them. This fear can feel stronger than the fear of experiencing IPV (Wilson et al., 2019).

- The perpetrator’s increasing surveillance of their partner’s activities can lead to safety concerns about being seen to access a family violence service (Wilson et al., 2019).

Fear that tamariki will be taken from mother

- The need to seek help could be suppressed by fear that approaching services for assistance risks having their tamariki taken into state care (Kaiwai et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2019; Moyle, 2015).

Reputational barriers

- Word of mouth relating a bad experience could make others reluctant to engage with a service (Carswell, Donovan and Kaiwai, 2019; Dickson, 2016a).

- Previous bad experiences with services can make people reluctant to access other services, particularly where people feel judged and humiliated. This can inhibit them from using a service or from actively engaging in programmes (Baker, Carswell, o-Hinerangi, 2016; Richardson and Wade, cited in Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2016:105).

- Perception about what a service does and who the service is for can be a barrier (Campbell, 2014; Carswell, Donovan & Kaiwai, 2019; Dickson, 2016a).

- Stigma and shame about accessing family violence or sexual violence services can be a barrier (Campbell, 2014; Carswell, Donovan & Kaiwai, 2019; Dickson, 2016a).

Cultural barriers

- Negative experiences with mainstream services where the service approach and the way the service workers treated the service user were not culturally appropriate, and they may have felt judged, uncomfortable, unable to relate with workers, frustrated, etc, can be a barrier (Carswell, Donovan & Kaiwai, 2019; Begum & Rahman, 2016; Dickson, 2016a; Hauraki & Feng, 2016; Te Wiata & Smith; 2016; Va’afusuaga McRobie, 2016; Wharewera-Mika & McPhillips, 2016).

Practical barriers

- Lack of ability to get to service can be a barrier, e.g. no transport available, inability to afford transport (Ministry of Social Development, 2019a; Lambie & Gerrad, 2018).

- Time service is available can make it inaccessible because of other commitments such as work, caring for children or other care commitments (e.g. Campbell, 2014).

- Geographical location can be a barrier – lack of services in area, distance and time to travel to services (Ministry of Social Development, 2019a; Campbell, 2014).

Awareness of services

- For some populations, such as people who use violence, there can be a lack of awareness about where to go to get help and support to change their behaviour (Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2020; Campbell, 2014; Carswell, Donovan & Kaiwai, 2019).

Delays to access

- Services may not be available when people are ready to access it because of capacity, resulting in waitlists or people not meeting the eligibility criteria (Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2020; Carswell et al., 2015).

- Many studies note timeliness is important because there is thought to be higher engagement if people can access a service when they identify they need it (Carswell, Frost, et al., 2017).

- There can be delays in being able to access services because justice institutions pass on insufficient contact information to service providers for referrals (Paulin et al., 2018).

Motivation and readiness to engage - perpetrators

- Given most people referred to non-violence programmes are mandated to do so, there can be reluctance to attend programmes and resistance to engagement (Carswell, Frost, et al., 2017; Roguski & Gregory 2014). Mandated clients can be encouraged to engage and motivated to make changes as outlined below.

3.3.3 Enablers for service access and engagement

The following approaches for enabling access and engagement with services are highlighted in the literature.

Kaupapa Māori and whānau-centred approaches

The distinctive characteristic of the kaupapa Māori approach is that it enables positive change through the use of traditional values such as whakapapa, whanaungatanga, mana wāhine and mana tāne to ‘reconnect participants to tikanga, affirm their cultural identity as Māori, and emphasise the contemporary relevance of tikanga as providing a cultural compass to guide their engagement with whānau’ (Paulin et al., 2018, p. ix).

Being whānau-centred is crucial for engaging wāhine Māori:

A key consideration for wāhine was to prioritise whakapapa (the sanctity of whānau genealogy), which committed wāhine to tāne thereby establishing a lifelong connection to protect the biological interest of their tamariki and their ties to whānau. Notably, the commitment wāhine had to maintaining the whakapapa connections of their tamariki to their father and his whānau was significant and frequently guided their decision making. (Wilson et al., 2019.)

Te Puni Kōkiri is co-designing and testing whānau-centred, strengths-based approaches to enable localised solutions and continuous improvement ‘to restore and establish healthy, safe, and functional whānau relationships’ (Were et al., 2019, p. 5). This initiative is initially being developed with four partners – Co-Lab Ōtautahi, Waikato Coalition, Kōkiri Marae (Lower Hutt) and Ōrongomai marae (Upper Hutt). The main focus of each partner is different:

- Waikato Coalition – to address the impacts of violence and the drivers/underlying causes of violence;

- Kōkiri Marae – to improve the programmes and services for whānau being delivered by themselves and the Kōkiri women’s refuge, including establishing a shared whānau-centred family violence facilitator role and case management of four to five whānau; and

- Ōrongomai Marae – to enhance services to whānau, including kaupapa Māori living without violence programme for tāne, strengthening workforce capacity and creating connections with marae and marae activities (Were, Spee, et al., 2019).

The Co-Lab Ōtautahi is a collaboration formed by several service providers with expertise in the use of whānau-centred, strengths-based, kaupapa Māori approaches in a family violence context. They have developed Te Herenga Tāngata (THT) ‘to create a “new door” for whānau who do not come to the attention of services or who may not choose to access services, and one that whānau enter by choice – not by force’ (Were, Spee, et al., 2019, p. 19). One of the key components is the establishment of three kaimahi (‘weavers’) at the Co-Lab providers, who act as a triage unit to assess which services and staff would be most suitable for whānau. These kaimahi roles also serve to connect each of the member/partner providers of the Co-Lab. Another primary goal is to engage and connect whānau with healthy spaces through a series of initiatives and events, as well as their existing programmes (Were, Spee, et al, 2019).

Enabling service access and engagement for people who experience violence

Acknowledging women’s competency in keeping themselves and their children safe

A strengths-based approach (as opposed to deficit based) focuses on capabilities and potential, recognising, for example, the strength, courage and resources required for women to keep themselves and their children safe within adverse situations. IPV has a traumatic impact on women emotionally, physically, cognitively and spiritually. However, researchers have found that these women display competency in the attitude, knowledge and skills they apply to their situations. They use a range of skills and strategies to enhance their survival and that of their children, through the process of moving away from IPV and this competency should be acknowledged by service providers. Using a strengths-based supportive approach is also more likely to be successful in terms of engaging clients (Wilson et al., 2019; Paulin et al., 2018; Crichton-Hill, 2013). The following is also important:

A complex response system is required that incorporates safe housing; personal development and determination enhancing activities such as individual or group counselling, and assistance with gaining employment; and health, nutrition and exercise programmes. Services need to be responsive to the physical, practical, and emotional needs that women have. (Crichton-Hill, 2013, p. 15.)

Client-centred and empowering practise for victims/survivors

Wharewera-Mika & McPhillips (2016) emphasise the importance of values-based services. They state: “Fundamental premises arising from this values-based orientation to sexual violence and supported by knowledge of trauma, are client-centred and empowering practise:

- Begin from a place of respect for victims/survivors and their personal strengths and needs

- Develop relationship and rapport

- Sensitively ascertain what this victims/survivor’s needs are, with regard to who they are as an individual and how they are responding to what they are experiencing. Assist victims/survivors through their decision-making process if need be.

- Assist victims/survivors through in getting their needs met

- Advocate for respectful and informed treatment by others.” (Wharewera-Mika & McPhillips, 2016, p.17)

Children/young people

Support for children should be ‘whānau-centred, relationship-based and empowering’ (Liston-Lloyd, 2019, p. 5). A study examining what supported resilience and positive outcomes for children conducted with 50 adults who had experienced adverse childhoods identified the importance of positive supportive relationships and a ‘child-centred’ approach when working with children:

A child-centred approach is necessary, especially for child protection, justice, education and health services, which has implications for policy and workforce development to ensure that workers have the guidance and skills to implement this approach… Positive, supportive relationships are key to facilitating resilience for children, young people and adults. Therefore, the findings support the need for initiatives that fund mentors, role models and community support networks. (Carswell, Kaiwai, et al., 2017, p. 5.)

Children and young people who have been taken into care want to be helped to stay in touch with their family or whānau and the people they care about, and want to be involved with their family or whānau in decisions that affect them (Office of the Children’s Commissioner, 2018).

Enabling service access and engagement for people who use violence

Motivational strengths-based approach

Similarly, the use of strengths-based approaches to engage people who use violence are identified as important. Many studies have found that the qualities of practitioners contacting and working with clients is crucial to engagement. Positive feedback from clients about why they engage relate to the way they perceive staff and the way they are treated, for example, the authenticity of staff, their sincerity, caring, lack of judgement and informative style, offers of therapeutic and practical support. Strengths-based motivational approaches are found to encourage people to think about change, often referred to as ‘planting the seed’, and to support them to engage in programmes, counselling and pro-social activities to help them make those changes (Campbell, 2014; Carswell, Moana-o-Hinerangi, & Gray, 2014; Roguski & Gregory, 2014).

Voluntary service participation

Voluntary participation was key to initial engagement because voluntary participants were, to some extent, open to the possibility of change (Roguski & Gregory, 2014). Other studies have found that mandated programme participants can engage with non-violence programmes with the support of motivational strengths-based approaches, engaging with facilitators and other group participants, and if they relate to the programme material and delivery style (Paulin et al., 2018; Carswell et al., 2015).

Timeliness of contact

Proactive contact shortly after a family violence episode was found likely to increase engagement, as people were more open to receiving support to make changes at that point (Carswell et al., 2014).

Awareness and accessibility of services

Awareness and accessibility of services was increased by proactive contact and, in the case of ReachOut (a North Canterbury and Christchurch initiative), the use of inviting marketing material. Free services and outreach capacity enhance accessibility (Carswell, Frost, et al., 2017, p. 3; Roguski & Gregory, 2014).

Helpful components of non-violence programmes

The evaluation of Ministry of Justice-funded family violence programmes found it was helpful for users of violence in terms of ‘understanding the dynamics of family violence and their potential role in it; learning more about themselves – their triggers and early warning signs; learning how to change their thinking; and improving their communication and listening skills’ (Paulin et al., 2018, p. 48).

Family Violence Death Review Committee (2020) analysis identified the following service approaches can support men to move away from violence:

In a context where few community resources are available for men who want to stop using violence, professionals have very limited support for working with men… These men come from different cultural backgrounds, with different experiences in childhood and during their development. However, all of them do have the capacity to move away from using violence when services:

- use strategies that recognise the relationship between structural and interpersonal violence

- focus on healthy masculine norms to promote behaviour change, responsibility and accountability

- reconnect men with positive forms of social support, including cultural reconnection and restoration

- engage wider organisation structures, families, whānau and communities in the change process

- set an expectation that men as fathers can make a positive (rather than violent) contribution to the family environment. (Family Violence Death Review Committee, 2020, p. 17.)

Enabling service access and engagement for diverse populations

Enabling diverse populations to access services involves both an awareness and understanding of diverse perspectives and needs of different populations and a service system that is responsive. This includes having enough services to meet the needs of different populations as well as building capability in mainstream and specialist services to engage and respond appropriately. For example, Carswell, Donovan and Kaiwai (2019) in their review of effective recovery services for men who have been sexually abused (as children and/or adults) identify the following factors to improve service access and delivery:

- Recognising and understanding diversity both across and within broad population groups, for example iwi, Pacific cultures, diversity of rainbow communities, and the needs of people living with disabilities.

- Understanding the values, beliefs, world views and approaches to health and wellbeing combined with good practices, such as cultural and needs assessments.

- Supporting the implementation and continual development of good practice guidelines for all population groups.

- Supporting culturally-based organisations such as kaupapa Māori organisations to respond to the needs of men who have been sexually abused, and their whānau. (Carswell, Donovan, and Kaiwai, 2019, p. 7.)

Pacific Peoples

Enablers to accessing family violence services for the Pacific Peoples include:

- community development approaches,

- working in collaboration and inter-sectorally,

- trained and knowledgeable staff,

- caring and committed staff and volunteers,

- effective resources (translated resources), and

- leadership in the community (Church Ministers and Elders) (Allen & Clarke, 2017b, p. 102.).

People with disabilities

People with disabilities who experience family violence have the same needs as other people in the same situation. However, they may also have specific needs that are related to their disabilities. Service providers can enable people with disabilities to access their services by:

- Making it clear that people with disabilities can access their support

- Having safe accessible routes into and within service facilities

- Having access in appropriate ways to all necessary information while using services and to help the make informed decisions on appropriate referral options.

- Having appropriately trained staff who understand and can meet their needs.

- Having policies and practices that won’t impede their gaining access to support. (Robson, 2016, p. 26.)

3.4 General population experiences of the ‘family violence service system’

This section provides some recent examples from the literature of victims and perpetrators experiences of the family violence service system.

Examples of navigating service systems

Families and whānau experiences of the Integrated Safety Response

Integrated Safety Response (ISR) is an example of a good integrated practice that has dedicated specialist roles and services to work with individuals, families and whānau to support both victims and perpetrators of family violence. Through ISR, families and whānau have quicker access to the support services they need. In an evaluation, many of the ISR service providers cited this speedy access as the ‘primary strength of the model’ (Mossman, Wehipeihana & Bealing, 2019, p. 34).

Gravitas Research and Strategy Ltd (2018) Improving the Justice Response to Victims of Sexual Violence: Victims Experiences

Qualitative research with 39 victims of sexual violence who had made a Police complaint and went through the court system. This study found the justice process can cause re-victimisation and re-traumatisation for victims of sexual violence. It also found that:

- Victims described that their needs were not always considered by the justice system – e.g. feeling unsafe in and around the court because of the presence of the offender and their supporters. Victims also described how difficult it was going through the court process which could take years.

- Victims’ rights were not always upheld through the justice system, most particularly in relation to (a) access to services, (b) entitlement to a restorative justice meeting, (c) provision of information, (d) offender name suppression and bail conditions, (e) privacy, (f) return of property taken in evidence.

Law Commission (2015) The justice response to victims of sexual violence: criminal trials and alternative processes had 82 recommendations to improve victims’ experiences of courts and alternatives to criminal trials. The Government proposed to address all the recommendations. For example, the Sexual Violence Bill proposed the following law changes to improve sexual violence victims’ experiences of the justice system:

- enable sexual violence complainants to give evidence and be cross-examined in alternative ways – e.g. by audio-visual link or pre-recorded video;

- ensure that specialist assistance is available for witnesses who need help to understand and answer questions;

- tighten the rules governing disclosure about a complainant’s sexual history to better protect against unnecessary and distressing questioning;

- ensure that trial evidence is recorded to prevent complainants having to repeat their evidence at future retrials;

- better support and protect sexual violence victims giving their victim impact statements in court; and

- give judges certainty to enable them to intervene in unfair or inappropriate questioning and to address common myths and misconceptions about sexual violence.

The package of legislative changes sits alongside specialist, best practice education and training for lawyers and judges, and existing operational improvements in courts. Through improved facilities, better information for victims and training for frontline staff, the Ministry of Justice plans delivering safe and appropriate services for court users.32

Women’s experiences of the Family Court

The Backbone Collective (2017) Out of the Frying Pan and into the Fire: Women’s experiences of the New Zealand Family Court.

A survey of 496 women who had used the Family Court found that:

- All of the women taking part in the survey had experienced forms of violence and abuse and 50% told us they experienced litigation/legal-abuse.

- Wāhine Māori are more likely to experience racism and find that cultural beliefs and practices are not comprehended in the FC.

- 417 women said their experience of violence and abuse was not believed or responded to, was minimised, or was not accepted into evidence.

- 83% of women told us the FC treated their abuser as safe.

- 58% of women attending FC-related appointments, fixtures, or hearings have been threatened, intimidated, or physically assaulted by their abuser.

- 93% of women do not feel psychologically or physically safe when the FC forces or coerces them into joint activities with their abuser.

- 155 women said the FC had forced their child/ren to spend time with the abuser. All of these women were worried about their child’s safety while in the abuser’s care.

The Backbone Collective believes the only way to safely and robustly determine whether the failures in the Family Court that are highlighted in their report are accurate and as widespread as the report suggests is to conduct a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the New Zealand Family Court.

Effectiveness of Ministry of Justice funded Domestic Violence Programmes for victims and offenders

An evaluation of Ministry of Justice (MoJ) funded domestic violence programmes (non-violence, adult safety, and Kaupapa Māori) conducted in 2017-2018 found some positive findings for victims and offenders (Paulin, Mossman, Wehipeihana, Lennan, Kaiwai, Carswell 2018). The evaluation design was a partnership between tauiwi and kaupapa Māori researchers. The evaluation involved interviews with 64 adult users of DV programmes and 21 stakeholders (including four mainstream service providers and three Kaupapa Māori service providers); online survey of providers of programmes; analysis of client evaluations of programme from 488 clients; literature review; and review of administrative data; and a re-offending study conducted by MoJ.

There is reasonably strong evidence from the reoffending study that Ministry-funded non-violence programmes are effective for those who attend a programme (whether offered through a Kaupapa Māori or mainstream service) following a non-mandated referral through the criminal court.

The key findings of this study are that those in the ‘active treatment’ group (compared with matched ‘controls’):

- were significantly less likely to commit a further family violence offence or a non-family violence offence in the following 12 months

- committed up to 46% fewer family violence offences and 49% fewer non-family violence offences in the following 12 months.

The findings from the MoJ re-offending study are further supported by the evaluation interviews with 40 participants of non-violence programmes; and findings from the 488 clients who provided feedback via their provider in 2017.

Nearly all the 40 non-violence programme participants reported some positive changes they attributed to programme participation including: reductions in their use of violence; improved relationships; a greater self-awareness of their triggers and improved skills for self-control. A small number described the programme as ‘life changing’, with one crediting a programme facilitator with saving his life. Many also thought the programme was not the full answer and would like continued support such as counselling and follow-up programmes (Paulin et al., 2018).

The evaluators interviewed 24 women who had participated an adult safety programme and most reported increased feelings of safety following programme completion, although one third still reported some fear for themselves and/or their children from their partner or ex-partner. Most of the women who had completed an adult safety programme and had separated reported improvements in their mental health - including increased self-confidence or feelings of self-worth.

Mechanisms for participants successful engagement and learning related to the skill of programme facilitators – especially those with a shared experience of family violence. This reinforces findings from many other studies about the importance of the relational aspects of programme engagement and feedback from participants often relates to facilitators qualities such as authenticity, relatability, and skills of practitioners. The preferred learning style was more conversational and interactive, and a warm physical environment and access to hot drinks and kai, were also identified as more conducive to learning.

Cultural knowledge, values, tools, and practice models produce positive outcomes for Māori participants in Ministry of Justice-funded domestic violence programmes to achieve safe and healthy whānau.

What differentiates Kaupapa Māori services from mainstream services is the weaving of tikanga Māori (cultural principles, practices, and values) and mātauranga Māori (traditional knowledge) throughout all aspects of the Ministry of Justice funded domestic violence programmes.

Māori cultural concepts are foundational; traditional values such as whakapapa, whanaungatanga, mana wāhine and mana tāne are used as the foundation to bring about positive change. Kaupapa Māori programmes reconnect participants to tikanga, affirm their cultural identify as Māori, and emphasise the contemporary relevance of tikanga as providing a cultural compass to guide their engagement with whānau.

Participants of programmes delivered by Kaupapa Māori providers connected with and valued the sharing of mātauranga Māori and tikanga Māori. They liked how tikanga was shown to be applicable and relevant for how they lived their lives today. This included the roles of men and women (mana tāne, mana wāhine); reiterating the sanctity of wāhine (te wharetangata) and re-establishing the roles of men as protectors and nurturers. Violence was depicted as a transgressing tikanga (mana, tapu and whakapapa).

3.5 Māori whānau experiences of the ‘family violence service system’

In the literature reviewed for this report, there were several common themes for Māori, including the need for:

- genuine partnership between Māori and government based on Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi);

- understanding family violence (and sexual violence) for Māori within the broader socio-political context, including the causal risk factors that increase Māori exposure and/or vulnerability to violence, the impacts of colonisation and institutional racism;

- reorientation to a service system (i.e. ecosystem) that supports holistic, whānau-centred and equitable responses to violence;

- a focus on primary prevention, with stronger investment in a ‘service continuum’ that builds social and cultural capital (i.e. Whānau Ora) alongside education, therapy and rehabilitative supports, programmes and services;

- increased resourcing for tikanga and kaupapa Māori-based supports, services and programmes; and

- the devolution of decision-making and investment to whānau, hapū, iwi and communities impacted by violence and that account for diversity and tailored solutions relevant to Māori needs, aspirations and rangatiratanga (i.e. Māori-led solutions for Māori).

The literature reviewed also highlighted that government engagement with Māori needed improvement and that Māori views within final reports, for example, were often indiscernible from non-Māori. This is consistent with the findings from other studies and reports that Māori ‘have noted their knowledge and interests were devalued and they experienced racism and tokenistic engagement. Some indicated it took considerable effort to establish credibility, be heard, have impact, and navigate advisory meetings, but even then their inputs were marginalised’ (Came et al, 2019, p 1).33 Even when Māori views or recommendations were taken up, it was often ‘piecemeal’ and implemented without understanding of the wider tikanga connected to them.34

As stated in a previous chapter, Māori are four times more likely than non-Māori to be killed by family violence (He Waka Roimata, 2019). This is a critical issue for whānau because of the very low levels of reporting and the high rate of recidivism, particularly within Māori communities, with only 20% of family violence and only 9% of sexual violence reported to the Police.35 The Oranga Tangata, Oranga Whānau inquiry into mental health and addiction also noted that whānau in a family violence situation tended to ‘refuge’ each other rather than reach out for help.

Whānau experiences of current services and the system were that it was fragmented, difficult to navigate, culturally inaccessible and punitive, and that it didn’t account for the multidimensional and broader social, cultural, political and historical context of Māori and the causes and impacts of family violence. Whānau, in particular, spoke of shame and fear of engaging in the system, disparaging attitudes, racism, victim blaming, punitive sanctions, inconsistent and inequitable treatment when engaging with agencies and services or the frustration they felt of having to repeat (or defend) their story to multiple agencies and services.

Wāhine Māori and their tamariki were identified in the literature as particularly vulnerable to family and sexual violence. Wāhine Māori were also more likely to carry the burden of whānau alone.36 This vulnerability was compounded by structural disadvantages (i.e. institutional racism) in which wāhine Māori were likely to be retraumatised by the state system.37 Hence, strengthening of the whānau structure alongside programmes and interventions that built whānau capability and capacity to better support each other were seen as key (Dobbs & Eruera, 2014; Kaiwai et al., 2020).

Two recent reports (Kaiwai et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2019) highlight the need for significant changes to mainstream approaches to supporting Māori whānau experiencing family violence and child maltreatment.

Whānau experiences of Oranga Tamariki practices around the removal of Māori children

Kaiwai, H., Allport, T., Herd, R., Mane, J., Ford, K., Leahy, H., Kipa, M. (2020). Ko Te Wā Whakawhiti, It’s Time For Change: A Māori Inquiry into Oranga Tamariki – Report. Commissioned by Whānau Ora. Wellington.

To make participation as accessible as possible, the Inquiry devised several pathways for submission and 1100 people throughout Aotearoa New Zealand engaged in the Inquiry process. The Inquiry found that:

The overwhelming and consistent message that the current State care and protection system simply does not work for any of the stakeholders involved – tamariki, whānau, care-givers, social workers or other kaimahi – was reinforced throughout the submissions, and pointed to a complex systemic mix of inadequate political representation, political bias, and adverse policies. The effects of service fragmentation and sectoral competition, inadequate and siloed funding systems, faulty sub-contracting and one-dimensional deliverables, was underpinned by the reliance of Western knowledge systems over Mātauranga Māori understanding, and Kaupapa Māori practice. (Kaiwai et al., 2020.)

The Inquiry recommended a suite of actions for the way forward based on a whānau-centred, systems-focused, kaupapa Māori-aligned, mātauranga Māori-informed approach. For example, issues with navigating the Oranga Tamariki system were raised throughout submissions, interviews and hui. Whānau spoke of their sense of powerlessness within a system that seemed to have no clear, consistent procedures and that made it virtually impossible to ‘jump through the hoops’ of getting tamariki back with whānau.

Significantly, these statements from whānau were largely consistent with findings from previous research, which found that Māori whānau lacked knowledge about Oranga Tamariki and the Family Court system. The research concluded that this lack of knowledge was a significant barrier to meaningful whānau involvement in the process concerning the welfare of their children. Combined with the lack of access to resources and relevant support to help Māori whānau understand the system, Māori whānau had little influence on decisions about their tamariki.

Kaiwai and colleagues (2020) made the following recommendation to government to better support whānau to access and navigate services for their tamariki:

Action point 1: Supporting whānau – strengthen whānau capability and capacity

A) Develop supports and resources that empower whānau Māori who are involved with Oranga Tamariki, including legal resources and resourcing for whānau, clear and coherent communication and complaints pathways, high quality navigation services, as well as other needed wrap-around supports and services, particularly for wāhine Māori. These supports need to be localised and targeted for maximum efficiency.

B) Establishment of a nationally funded helpdesk for whānau who need immediate help with care and protection of tamariki. An 0800 number and contacts for people/providers in the community that can help, including legal advice and resourcing for whānau; navigational services to include a wrap-around support system for whānau. 24/7 ‘By Māori – For Māori – With Māori’ crisis centres for whānau need to be established in all regions, with easy to access follow-up in kaupapa Māori organisations.

Wāhine Māori experiences of family violence and service support

Wilson, D., Mikahere-Hall, A., Sherwood, J., Cootes, K., & Jackson, D. (2019). E Tū Wāhine, E Tū Whānau: Wāhine Māori keeping safe in unsafe relationships. Taupua Waiora Māori Research Centre, AUT, Auckland, NZ. Funded by Marsden Fund.

To examine Wāhine Māori experiences of IPV, this study used a kaupapa Māori research methodology that privileged a Māori worldview to conduct in-depth interviews with 36 participants from throughout Aotearoa: 28 wāhine Māori who had lived in an abusive or violent relationship and were currently living violence-free; eight tāne, seven of whom had used violence; and one facilitator of a kaupapa Māori men’s group.

This study highlighted the intersectionality of multiple forms of oppression that led to them becoming entrapped:

… contexts are layered with multiple and compounding forms of oppression; Māori ethnicity, welfare dependency, contemporary and historical trauma, colonisation, education, unpaid or no employment, health and socioeconomic disparities, racism, and gender.

Wāhine encountered the following ‘unseen fences’ while keeping themselves and their tamariki safe:

- their own fears and capabilities at specific times;

- their partners’ increasing psychological abuse and controlling behaviours;

- the people in services they need; and

- the accessibility and availability of services.

Findings related to the FV service system highlighted that mainstream services were usually unhelpful, which reinforced their thoughts about no real help being available, and sometimes compromised their safety. Fear of their tamariki being taken also acted as a barrier to seeking help.

Whānau experiences of the Integrated Safety Response pilot

Wehipeihana, N.(2019). What’s working for Māori? A Kaupapa Māori perspective on the responsiveness of the Integrated Safety Response pilot to Māori Synthesis Evaluation Report. Commissioned by Ministry of Justice – Joint Venture Business Unit, Wellington.

The kaupapa Māori evaluation of ISR reported overall, there is ‘good’ evidence that ISR is responsive to Māori when assessed against the whānau-centred delivery model. The evaluation also found:

- ISR is highly responsive to whānau;

- Whānau-centred practice has increasingly become a core feature of ISR; and

- ISR has become more responsive to Kaupapa Māori partners.

3.6 Other population-based groups experiences of the ‘family violence service system’

In this section, we examine research focused on the experience of the family violence service system among specific populations – Pacific peoples, those of other ethnicities (non-Māori, non-Pacific, non-Pākehā), male victims/survivors, LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community, people with disabilities, and older people.

Twenty-four reports included in this review focused on other population-based groups. Of those, eight focused on Pacific people, six on people of other ethnicities, two on male victims/survivors, two on LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community, two on people with disabilities and four on older people.

3.6.1 Pacific Peoples

Family violence is a significant issue for Pacific Peoples living in New Zealand. According to the New Zealand Crime and Victims Survey, 6.17% of adults in New Zealand who experience family violence identify as ‘Pacific Peoples’. This compares with 4.29% of NZ European and 7.3% of Māori (Ministry of Justice, 2019). Additionally, the average annual mortality rates for Pacific Peoples from family violence were 1.5 per 100,000 between 2002 and 2006, compared with a rate of 0.7 per 100,000 for the whole NZ population.

A paper discussing Pacific perspectives on family violence by Fa’alau & Wilson (2020) critically analyses and interprets information available about family violence using a Pacific lens. Their key messages include:

- ‘Mainstream’ family violence initiatives and programmes are not usually effective for Pacific Peoples. Using Western tools and ideologies for interventions is not ideal for addressing issues of family violence for Pacific families and communities, given the differences between common Pacific perceptions and meanings of issues of violence.

- There is a need to accommodate Pacific worldviews to deliver meaning and information about violence into policies, funding allocation and strategies developed by the government. Funding criteria should allow each provider to develop a service that reflects their organisation’s philosophical base, incorporating the Pacific cultural norms and culture within which it works.

- Interventions and therapies for Pacific communities that acknowledge cultural diversity should be used where appropriate. A ‘one size fits all’ approach provides limited ability to consider the diversity of Pacific families' cultural backgrounds, paths to violence and required interventions. Family violence is complex, which requires practitioners to match interventions to a wide range of people and different types of family structures.

- Holistic approaches to intervention and prevention for Pacific communities need to be used to address the complexities of cultural, communal and church issues when working with survivors of violent abuse and perpetrators of violence.

- Currently, access to culturally safe therapy is limited. Selected therapists, many who are not trained to work with Pacific communities, are appointed as part of many funded initiatives and programmes targeting violence.

- ‘Family’ in Pacific culture is central to people’s being. Therefore, individuals usually identify themselves within the context and relational connection to their families or communities. Working from a holistic approach means working with the whole Pacific family to address and prevent family violence and monitor the progress after the intervention (Fa’alau & Wilson, 2020, p. 1).

A qualitative research report using a ‘talanoa’ approach explored Pacific Peoples’ experiences of the sexual violence service system, ‘Working with Pacific survivors of sexual violence’ by Va’afusuaga McRobie (2016), which is part of the TOAH-NNEST suite of studies. The authors note that mainstream sexual violence support providers report that ‘Pacific women want to stay in mainstream for anonymity’ (Va’afusuaga McRobie, 2016, p. 4). This reinforces the need for workforce development in relation to cultural competency for mainstream service providers. Dickson’s (2016a) research on experiences of intimate partner violence and sexual violence within the LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community, ‘Māori and Pacifica participants reported culturally inappropriate responses when trying to get help which assumed violence was “normal” for them’ (2016a, p. 13).

Research has shown that Pacific Peoples are more likely to access informal rather than formal support systems. However, there is a demand for information on Pacific-based services delivered by Pacific people who speak the same language and have a deep understanding of their culture (Wharewera-Mika and McPhillips, 2016, p. 48).

A ‘culture of silence’ among Pacific communities in terms of family violence has been identified by researchers (e.g. Pasefika Proud, 2012; Ministry for Women, 2015), in terms of how violence and threats of violence are regularly ignored and go unchallenged in the community. When such behaviour ‘is not effectively addressed it can be perceived as community endorsement of violent behaviour and attitudes’ (Ministry for Women, 2015, p. 15). This, in turn, contributes to a reluctance to disclose family violence to avoid the associated stigma and shame (Ministry for Women, 2015).

High reported IPV prevalence rates (22.9%) were found in a New Zealand study of new Pacific mothers, two-thirds of whom were born outside of NZ (Paterson et al., in Boutros et al., 2011, p. 9). Additionally, Pacific children have high rates of hospitalisation in New Zealand from assault, neglect and maltreatment – 24.36 Pacific children per 100,000, as compared with 11.71 European/Other children per 100,000 (Pasefika Proud & Ministry of Social Development, 2016).

In 2012, a major issue was highlighted regarding the lack of research on specific Pacific ethnicities in relation to family violence, e.g. the cultures of Cook Islands, Fiji, Niue, Samoa, Tokelau, Tonga and Tuvalu, in conjunction with the assumption that Pacific Islanders are a homogeneous group as mediated by Western perceptions and interpretations (Pasefika Proud, 2012). The lack of research prompted the Pacific Advisory Group to set up a research committee, the Pasefika Proud Research Komiti (PPRAK), and develop a research agenda, with funding from the Ministry of Social Development. Three areas of priority were highlighted:

- generation of Pasefika knowledge(s) where the focus is on social and kin relationships;

- service delivery where the focus is provider–funder responsibilities and service quality; and

- workforce development where the focus is the design, development, delivery and evaluation of Pasefika nations training programmes and the creation of databases to identify Pasefika needs and workforce targets (Crichton-Hill, 2018).

The Pasefika Proud research committee has undertaken several studies on specific cultures, including:

- a 2018 literature review of family violence initiatives from the United States of America, Canada, Australia, Hawaii, the South Pacific region and Aotearoa New Zealand with a view to adapting them for Pacific men in Aotearoa New Zealand;

- a 2015 study to explore current New Zealand-based Samoan people’s understandings of primary prevention of violence against women; and

- a 2019 Tuvalu Family Violence Prevention Plan.

In addition, TOAH-NNEST updated their Good Practice Responding to Sexual Violence Guidelines for ‘mainstream’ crisis support services for survivors in 2016 to include mainstream support service guidelines for specific populations including Pacific Peoples.

3.6.2 Other ethnic groups

There is a lack of research about the experience of people from various ethnic communities of the family violence service system in Aotearoa. Our review includes six reports, two were part of the 2016 TOAH-NNEST Good Practice Responding to Sexual Violence Guidelines for ‘mainstream’ crisis support services for survivors, one report focused on Muslim women experiencing sexual violence (Begum & Rahman, 2016) and the other focused on Asian survivors (Hauraki & Feng, 2016). Another report was a family violence statistical analysis to disaggregate data by ethnicity (Paulin & Edgar, 2013) and two reports focused on family violence in refugee and migrant communities (Levine & Benkert, 2011; Boutros et al., 2011).

Simon-Kumar’sliterature review, Ethnic perspectives on family violence in Aotearoa New Zealand (2019), for the New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghousefound that:

Help-seeking behaviours, along with reporting, are relatively infrequent in ethnic communities. In part, this silence may reflect shame and fear of the stigma from and towards their communities that may be associated with disclosing violence. Low levels of help-seeking may also reflect the limited formal and informal avenues available to ethnic and migrant women where they can safely disclose their experiences. (Simon-Kumar, 2019, p. 1.)

The other key messages from Simon-Kumar’s (2019) literature review are:

- Violence directed against women in ethnic and migrant communities is prevalent in different age, sexuality and identity groups, but is underreported.

- Although there are similarities between violence against ethnic and non-ethnic women, violence in ethnic communities can take particular cultural forms, have distinct profiles of presentation and arise from a specific constellation of risk factors.

- Risk factors for interpersonal violence against ethnic women are layered and encompass individual (e.g. language barriers, isolation), household (e.g. migration factors, employment conditions), community (gender norms, patriarchal values) and systemic (racism, colonisation, capitalist structures) factors.

- Current interventions for violence against ethnic and migrant women take varied forms. Community-based specialist services alongside responsive ‘mainstream’ services have the potential to form an effective integrated intervention approach to addressing impacts of violence. Increasingly, there is recognition that services cannot be ‘one size fits all’ for ethnic and non-ethnic communities. Specific culturally sensitive approaches and techniques need to address the unique profiles of violence against ethnic and migrant women.

The statistical analysis commissioned by the Office of Ethnic Affairs confirmed that, although ‘there are significant gaps and limitations in the statistics relating to family violence in New Zealand, there is sufficient data to be certain that it remains one of our most pressing social problems, with a high prevalence in the population as a whole’ (Paulin & Edgar, 2013, p. 4). Unfortunately, many of the data sources only distinguish Māori, Pacific and Asian in terms of ethnicities. The others tend to be categorised as ‘other’, which is a combination of people in New Zealand ‘who identify their ethnic heritage as Asian, Continental European, Middle Eastern, Latin American[,] … African … [and] New Zealand European’ (Paulin & Edgar, 2013, p. 4).

Levine and Benkert (2011) undertook exploratory case study research on two community initiatives addressing family violence in refugee and migrant communities. They found several systemic issues that may prevent women from accessing support services, including:

- Refugee and migrant women were often isolated, both from the family support systems left behind in their country of origin and from mainstream New Zealand culture and its formal support systems. Isolation was identified as a risk factor for family violence in the research literature.

- Women who are dependent on their partners to meet immigration policy requirements for a temporary or residence visa may stay in abusive relationships to maintain their current immigration status.

- Although the Victims of Domestic Violence immigration policy was introduced in 2001, not all refugee and migrant women can use it. This may be because they are unaware of the policy, they are not eligible because their partner is not a New Zealand resident or citizen (that is, the partner may be on a student or work visa) or they may not be willing to go to the people or organisations competent to make a statutory declaration that domestic violence has occurred (Levine & Benkert, 2011, p. 4).

Boutros and colleagues (2011) highlighted ‘an interplay of disempowering factors [which] constrain the self-protective actions of refugee and migrant women and the effectiveness of external interventions’ (2011, p. 2). As well as language barriers, these factors included pressure to maintain traditional group cultural norms, fear of ostracism from their family and cultural community, a lack of awareness of their legal rights or of services available to them, the unsuitable nature of some support services and fear of poverty associated with reduced family and social support.

Family stressors that ‘can exacerbate family violence’ identified by Levine and Benkert (2011) included poverty and unemployment, and the influence of the host culture on young people. They also found that ‘some men used their culture and religion, and their standing in the community, to rationalise their coercive behaviour’ (Levine and Benkert, 2011, p. 5).

Boutros and colleagues (2011) summarise the outcomes for the women involved succinctly:

The consequence of having fewer options is that refugee and migrant women can be subject to a lifetime of continued abuse with its resultant mental and physical health consequences. Their abusive relationship may seem preferable to a life without family or status in the community and a life of poverty and isolation. (Boutros et al., 2011, p. 2.)

We note that the updated Family Violence Act includes dowry abuse, which recognises that this form of violence occurs in New Zealand.

3.6.3 Male victims/survivors

Our search of the literature found no New Zealand-based research on heterosexual men as victims of family violence or evaluations of strategies working with these men. We know that some services are working with male victims of family violence and that this area requires further attention. Some research on gay, transgender and gender diverse experiences of family violence, sexual violence and child abuse is examined in the next section.

There were two reports on male survivors of sexual abuse that are included in this review. The first is a literature review about effective recovery services for men who have been sexually abused as children and/or as adults (Carswell, Donovan & Kaiwai, 2019a & b). The second report, TOAH-NNEST Good Practice Responding to Sexual Violence Guidelines for ‘mainstream’ crisis support services for survivors (Mitchell, 2016), includes a section related to good practices working with men. However, not included in the annotated bibliography are the good practice guidelines developed by the Male Survivors Aotearoa (MSA) and the co-developed guidelines by MSA and Ministry of Social Development in 2018.38

Carswell, Donovan and Kaiwai (2019a) emphasise the importance of debunking myths (or ‘cultural delusions’) about the sexual abuse of males, given that the evidence shows that this is a significant and serious issue with severe impacts for boys and men. The New Zealand Crime and Victims Survey (NZCVS) 2018 surveyed 8030 people and found 12 percent of men experienced one or more incidents of sexual violence at some point during their lives (Ministry of Justice, 2019b, p. 82). Males can have difficulties disclosing their experience as ‘abuse’ because of myths such as ‘males cannot be abused’.

Mitchell’s (2016, pp. 4–9) qualitative research with male survivors of sexual abuse identified seven areas of importance to men when interacting with the sexual violence service system in terms of both disclosure and support through the recovery process. The findings have implications for workforce development, referral and interagency processes and communication, and the need for specialised education for professionals.

A summary of barriers for men seeking support for sexual abuse are:

- Men disclose sexual abuse at lower rates than women and often delay disclosing for years or even decades. The reasons for this include not knowing where to get support and fear of how they will be perceived and treated.

- Gender norms that promote an image of masculinity as dominant and tough make it harder for men to disclose abuse and lead to them being more likely to be viewed as a perpetrator than a survivor/victim.

- For Māori and Pacific men, barriers may include a lack of culturally responsive services and concerns about being treated in a discriminatory or culturally inappropriate way.

- Harmful myths exist about sexual harm against men and prevent men seeking support. These myths include ideas that men who have been abused ‘must be gay’ and that men who have been abused go on to be abusers themselves. These myths, although untrue, persist. They can cause distress to male survivors and affect how others respond to them if they disclose their abuse.

- A negative response to initial disclosure may be distressing and discourage men from seeking further help. Getting an appropriate response when first disclosing, even to non-specialist services, is essential to men seeking ongoing support. Professionals in the health and social sectors should be able to respond empathetically to disclosures of sexual abuse from men, in a way that is culturally appropriate, supportive and non-judgemental (Carswell, Donovan and Kaiwai, 2019b, p. 4).

Carswell, Donovan and Kaiwai (2019b, p. 4) provided a suite of recommendations to the government to support men who have been sexually abused, including:

… service developments should consider diversity, acknowledging and adapting services to meet the differences in men’s cultural and sexual identities. Support of existing population-based organisations and the development of new organisations may be needed to offer effective support for Māori, Pacific, ethnic communities, Rainbow/Takatāpui communities, and for men with disabilities.

The findings reinforce the importance of a range of service delivery options including outreach services, collaborative services, and online services, as well as accessible and available service locations.

Advocates are required to help clients navigate services and the justice system, brokerage of specialist services, and offer practical support – particularly for men with complex needs such as mental health issues, intellectual disabilities, addictions, poverty, and homelessness.

3.6.4 LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community

There are two reports on LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community, both authored by Sandra Dickson in 2016. One is part of the TOAH-NNEST research programme on guidelines for mainstream support services and the other, which was commissioned by an NGO called Hohou Te Rongo Kahukura – Outing Violence, examines the experiences of intimate partner and sexual violence in the LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community through an online survey and a series of hui held throughout the country. The report for TOAH-NNEST also drew on research findings from the Hohou Te Rongo Kahukura – Outing Violence study.

IPV and family violence are significant issues for the LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents had experienced unwanted sexual acts from partners, and one in five identified a family member as a perpetrator (this is likely to refer to child sexual abuse). In addition, more than half of them had experienced multiple incidents of emotional, verbal and psychological abuse, and, in terms of physical abuse, half had experienced being pushed or shoved by a partner and a third had experienced being slapped, punched or slammed into something hard (Dickson, 2016a).

In relation to their experience with the support service system, most of the survey respondents stated that they did not seek help at all because they considered their experience minor. This is despite the serious impacts that were reported earlier in the survey, which included feeling numb and detached, continued fear of their partner and concern for their safety, experiencing nightmares or hypervigilance and physical injuries (Dickson, 2016a).

Dickson (2016a) explains that ‘minimising violence by survivors is not uncommon … for people from Rainbow communities, the additional challenges in recognising partner and sexual violence are structured by the heteronormativity of dominant images of partner and sexual violence’ (2016a, p. 32). Other reasons for not seeking help include:

- not knowing where to go for help;

- not believing that they would be treated fairly;

- the fear of further violence or discrimination;

- having been warned not to by the perpetrator or friends and whānau;

- concerns about the support organisation being homophobic, biphobic or transphobic; and

- fear of being ‘outed’ by the organisation.

The LGBTQIA+/Rainbow community also faces challenges from mainstream violence support services who operate within a binary sex/gender framework and are ‘predominantly set up to respond to men’s violence towards women’ (Dickson, 2016a, p. 13).

For those who stated that they needed help, they required ‘specialist help’ for either IPV or sexual violence. Partner violence (sexual and other forms of IPV) also created greater needs for housing, income and financial support and healthcare. In terms of who was actually approached for help, help was more likely to be sought from friends and counsellors than specialist IPV/sexual violence agencies. Unfortunately:

… domestic violence agencies and New Zealand Police … were more likely to be not supportive or helpful … For domestic violence agencies, some respondents reported supportive and helpful experiences as well – for New Zealand Police these were in the minority, with poor experiences significantly more likely. (Dickson, 2016a, p. 36).

3.6.5 People with disabilities

There is a general lack of research on family violence as experienced by people with disabilities in Aotearoa. We have included two reports, one is part of the 2016 TOAH-NNEST Good Practice Responding to Sexual Violence Guidelines for ‘mainstream’ crisis support services for survivors (Robson, 2016). The other was an exploratory study commissioned by an NGO – Tairawhiti Community Voice – to increase understanding of the multidimensional nature abuse manifests in for disabled people and to identify individual and structural barriers that prevent disabled people from voicing and extracting themselves from abusive environments (Roguski, 2013).

Robson’s (2016) report largely recommends the need for support services to be accessible to people with disabilities. The requirements could apply to providers of any service rather than being specifically those related to violence. However, Carswell, Donovan and Kaiwai (2019) found that ‘people with intellectual disabilities are more vulnerable to sexual assault and face more barriers than other survivors in terms of reporting the abuse, including; not being able to fully recognise what has happened to them; and needing assistance or someone to report on their behalf’ (2019, p. 36).

In addition to a literature review, Robson (2016) draws largely on Roguski’s (2013) research to discuss the experience of abuse among disabled people. Robson (2016) asserts that recognising ‘violence as being not just physical, but also carried out through control, coercion and intimidation’ is particularly pertinent for people with disabilities (2016, p. 10). Roguski (2013) explores all types of violence of which disabled people are victims, including family violence and intimate partner violence.