Part 1: Introduction

1.1

In this Part, we set out:

- why we did the audit;

- what we looked at;

- our understanding of the joint venture approach; and

- how we carried out our audit.

1.2

New Zealand has high and enduring rates of family violence and sexual violence.2 These affect hundreds of thousands of New Zealanders every year. Successive governments have invested significant resources in trying to address these issues. However, those efforts have not resulted in a sustained improvement in outcomes.

1.3

The type of actions needed to address family violence and sexual violence do not fit neatly into the boundaries of government agencies. The Government has recognised that it needs to address this if efforts to improve outcomes are to be effective. In April 2018, the Cabinet Social Wellbeing Committee (the Social Wellbeing Committee) was advised that:

It will take transformational change across the system to support healthier, safer communities. This will require leadership, a collective commitment across multiple agencies to prioritise family violence and sexual violence efforts, the provision of new services that break the intergenerational cycle of violence, and stronger partnerships between government, NGOs and communities to deliver services that meet the needs of families.3

1.4

In September 2018, the Government announced that it would set up the Joint Venture for Family Violence and Sexual Violence (the joint venture) to find more effective ways of reducing family violence and sexual violence.

1.5

At the time of our audit, the joint venture consisted of 10 government agencies (the agencies). One of its aims is that reducing family violence and sexual violence becomes and remains a priority for the agencies.

1.6

The joint venture was made up of the agencies whose chief executives formed the Social Wellbeing Board in 2018, and three additional agencies. The Social Wellbeing Board is a cross-government group of chief executives. The work it oversees goes beyond the remit of a single agency. The Public Service Commissioner serves as the Board's independent chair.

1.7

During our audit, the agencies included Accident Compensation Corporation, the Department of Corrections, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Justice, the Ministry of Social Development, the New Zealand Police, Oranga Tamariki, Te Puni Kōkiri, and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.4

1.8

The joint venture is responsible for changing the whole-of-government response to family violence and sexual violence. The joint venture approach is intended to clarify the lines of accountability for reducing family violence and sexual violence, which were previously unclear.

Why we did the audit

1.9

New Zealand's high rates of family violence and sexual violence have widespread and enduring economic, cultural, and social costs.

1.10

These forms of violence disproportionately affect those facing compounding forms of disadvantage and discrimination. Māori women, Pacific women, young women, women on a low income, LGBQTI+ people, women in gang-involved families, people with disabilities, and the elderly are at a higher risk of experiencing these forms of violence than other people.

1.11

The consequences of violence are wide-ranging and often intergenerational. Children exposed to family violence and/or sexual violence can experience lifelong impacts on their development, ability to learn, and behaviour. Almost 80% of youth offenders grow up in homes with family violence. Children and young people exposed to violence attempt suicide at three times the average rate.

1.12

Responding to family violence and sexual violence involves significant public resources – of both people and money. For example:

- In 2017/18, more than 10,000 people started a sentence managed by the Department of Corrections where the lead offence was family violence. Most people in prison have witnessed or been victims of family and/or sexual violence.

- The New Zealand Police investigated more than 121,762 incidents of family violence in 2017 – about one every four minutes. This number increased to 133,022 in 2018.

- Family violence accounts for nearly half of all referrals Oranga Tamariki receives, and one in seven children report that they have been exposed to family violence.

- A 2015 analysis showed that the Government was spending $1.4 billion annually on family violence and sexual violence. The Government has committed significant spending to strengthen family violence and sexual violence services since that time.

1.13

Family violence and sexual violence are complex problems. The issues of violence are complex in themselves, and the strategies and interventions needed for those affected – and the fact that multiple agencies and individuals need to be involved in this – are also complex. The joint venture was set up to fundamentally change the way government agencies work together and with others to prevent, detect, and respond to family violence and sexual violence.

1.14

Provisions in the Public Service Act 2020 change the way that government agencies are able to work together. These changes mean that joint ventures and other cross-agency work arrangements could become an increasingly common feature of how the public service works.

1.15

We carried out a performance audit to look at the joint venture early in its development because of the:

- importance of reducing family violence and sexual violence;

- significant amount of public resources involved;

- joint venture's focus on transforming how government agencies work to address family violence and sexual violence; and

- likelihood that arrangements of this kind will become more common.

1.16

We want to provide an independent perspective on the progress of the joint venture that can support its development.

What we looked at

1.17

We set out to establish how effectively the joint venture has been set up to support efforts to significantly reduce family violence and sexual violence.

1.18

Our work focused on three main points:

- the context in which the joint venture was set up;

- whether the way the joint venture is organised supports the agencies to work effectively together and with Māori, communities, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in the family violence and sexual violence sector; and

- the extent to which the joint venture is creating a shared vision, joint delivery outcomes, and an ethos of shared responsibility and accountability.

1.19

When looking at how the joint venture is organised, we considered:

- whether the joint venture has effective leadership, governance, and capability in the right places, including ministerial oversight, governance arrangements, the role and functioning of the Deputy Chief Executive group, the role of the joint venture's business unit, and the involvement of Māori and the wider social services sector;

- the effectiveness of the joint venture in sharing and using knowledge and practice, and monitoring and measuring performance; and

- how well the joint venture has delivered the Social Wellbeing Committee's expectations to date.

1.20

We did not look at policy decisions about setting up the joint venture.

1.21

We have not looked at the work programmes and interventions of the individual agencies as part of this audit. We might carry out work on these aspects of the joint venture in the future.

Understanding the joint venture approach

1.22

The joint venture approach is about transforming the way government agencies work to address family violence and sexual violence.

1.23

The advice to the Social Wellbeing Committee (see paragraph 1.3) was that several factors indicated need for this fundamental change. A significant factor is that no single agency has been responsible for reducing family violence and sexual violence. No agency has been responsible for overall stewardship of the Government's system for preventing, detecting, and responding to family violence and sexual violence, strategy, and family- or whānau-centred responses. Accountability for working with families experiencing violence is fragmented. Different agencies work with children, victims, and perpetrators.

1.24

Other significant factors in the advice included:

- No agency has had the primary mandate, and therefore the interest, to make a case for the significant level of investment needed for integrated primary prevention and early intervention efforts.

- The issues had not been the collective priority of the relevant agencies. Each agency faces strong competing demands on its time and resources.

- Policy changes in one area can hinder improvements made in another, as well as the wider system response. For example, changes to one agency's funding criteria can affect the security of providers that rely on multiple funding streams.

- Government agencies have not always listened to the expertise of the sector, the communities, Māori, and others. Also, service providers are often not compensated for their efforts when they are asked for input. Engagement with the sector is not co-ordinated and sequenced to achieve collective objectives. Instead, individual agencies lead engagement on their separate responsibilities.

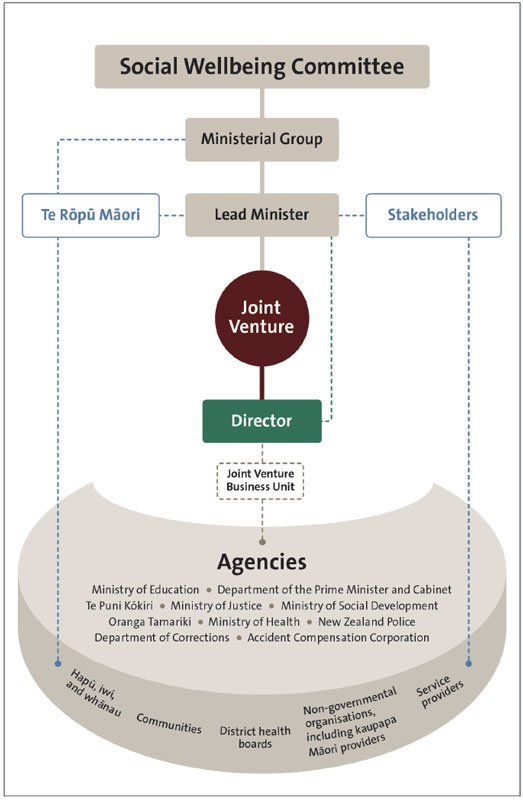

1.25

The joint venture has been designed to address these issues. Figure 1 sets out the joint venture's structure and relationships.

1.26

The chief executives of the 10 agencies form the joint venture's Board. They are collectively responsible for the performance of the whole-of-government response to family violence and sexual violence. Each chief executive is also individually accountable for their agency's contribution to the joint venture's work.

1.27

The joint venture involves new ministerial arrangements. The Social Wellbeing Committee oversees the joint venture, and a Lead Minister is responsible for day-to-day oversight.

1.28

The Lead Minister is also part of a Ministerial Group that was formed to, where possible, resolve issues affecting the joint venture and to develop and co-ordinate advice to the Social Wellbeing Committee. The Ministerial Group is a sub-group of the Social Wellbeing Committee and at the time of our audit included the Minister of Justice, the Minister for Social Development, the Minister for Children, the Minister for Seniors, and the Minister for Māori Development.

1.29

A Director supports the joint venture's Board in its role. The Director reports to the Board and has a day-to-day relationship with, and reports directly to, the Lead Minister. In addition, a joint venture business unit (the business unit) has been set up to support the Board and Director in carrying out their roles and functions.

1.30

The joint venture is tasked with working in partnership with Māori. To do this, the joint venture approach includes an independent Māori body (Te Rōpū Māori). The advice to the Social Wellbeing Committee stated that Te Rōpū Māori would:

… give effect to a partnership between Māori and the Crown (and especially for wahine Māori) to transform the whole-of-government response to family violence, sexual violence and violence within whānau. The interim Te Rōpū will work in partnership with the Crown, Ministers and the dedicated agent to deliver these shared goals, underpinned by the Treaty of Waitangi and the Crown's obligations to uphold mana motuhake.5

Figure 1

The joint venture's structure and relationships at the time of our audit

Source: Adapted from Cabinet paper (August 2018), Leadership of Government's collective efforts to reduce family violence and sexual violence.

1.31

In addition, the joint venture is expected to work with NGOs in the family violence and sexual violence sector, drawing on the knowledge and expertise of people working in those NGOs. To achieve this, the joint venture approach includes a commitment to working with stakeholder groups.

1.32

The joint venture was set up before the Public Service Act 2020 was passed. Because of this, it is not a joint venture as defined in that Act. The joint venture is also not a joint venture in the commercial sense, where the parties involved combine their collective resources in a new and independent entity that takes on responsibility for the work.

1.33

The joint venture is a new working arrangement that relies on the commitment of the agencies to navigate the tension between their individual and collective interests.6

How we carried out our audit

1.34

To carry out our audit, we:

- reviewed and analysed relevant documents from the joint venture;

- conducted more than 45 interviews with staff from the joint venture, including all Board members, the Director, all members of the Deputy Chief Executive group, staff from the business unit, and senior leaders and staff from the agencies; and

- spoke with representatives from the interim Te Rōpū, and NGOs in the family violence and sexual violence sector who have been involved in the joint venture's work.

2: Although there is no agreed definition of family violence, the Family Violence Act 2018 defines family violence as violence inflicted against a person by any other person with whom that person is, or has been, in a family relationship. Under this definition, family violence includes, for example, intimate partner violence, child abuse and neglect, sexual violence, elder abuse, parental abuse, and sibling abuse. It also includes psychological abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, financial or economic abuse, harm to pets or animals, dowry-related violence, and property damage.

3: Cabinet paper (April 2018), Breaking the inter-generational cycle of family violence and sexual violence, available at www.justice.govt.nz.

4: Changes were made to the membership of the joint venture in early 2021. We understand that the Ministry for Women and the Ministry for Pacific Peoples are now associate members of the joint venture. We also understand that the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet is now also considered an associate member. Associate members receive the papers produced for the Board of the joint venture and can attend meetings of the Board.

5: Cabinet paper (August 2018), Leadership of Government's collective efforts to reduce family violence and sexual violence, available at www.justice.govt.nz.

6: Cabinet paper (August 2018), Leadership of Government's collective efforts to reduce family violence and sexual violence, available at www.justice.govt.nz.