Part 2: Our observations on the 2021-31 consultation documents

2.1

In this Part, we:

- outline our views on what makes a consultation document effective;

- summarise what we saw in the 2021-31 consultation documents;

- detail some of the different approaches councils used to engage with their communities; and

- suggest it is an appropriate time to review the legislation about consultation documents.

Our views on effective consultation documents

2.2

When considering councils' 2018-28 consultation documents,4 we noted that effective consultation documents:

- highlighted issues and options and how these would affect communities, and included well-designed questions on the options facing the public;

- provided the key elements of the council's financial and infrastructure strategies as context for long-term plans;

- balanced contextual information to allow a community to participate in the consultation process with the issues being consulted on;

- were written in plain English and included tables, diagrams, and infographics in an easy-to-follow structure; and

- provided tips on how to read the information and clear indications of where to find the relevant underlying information.

2.3

Our views on what makes an effective consultation document have not changed after our review of the 2021-31 consultation documents.

What we saw in the 2021-31 consultation documents

2.4

The 2021-31 consultation documents varied significantly in their layout, length, and readability. This is to be expected, given councils have discretion over how to develop consultation documents that will resonate with their communities. The more effective consultation documents were clear about the challenges the councils were facing and written in a way that was easy to follow and in plain English.

2.5

We expand on these qualities below.

Councils were increasingly clear with their communities about the challenges they were facing

2.6

As we noted in Part 1, councils are working in circumstances that are increasingly uncertain. At the same time, councils are facing significant challenges. These include:

- responding to historical underinvestment in infrastructure;

- managing changing demographics;

- responding to increasing expectations from communities for improved services (whether these are smoother roads, improved recycling, or increased sustainability); and

- changing regulatory requirements either implemented (for example, new freshwater management standards) or to come (such as the new drinking water standards).

2.7

In our view, councils were clear in their 2021-31 consultation documents about the challenges they and their communities were facing and what approaches the council proposed to address these.5 We consider this a significant improvement from previous consultation documents.

2.8

Importantly, most councils used plain English to make it easier for their communities to understand the challenges and the proposed response. Given the complexity of the challenges, councils should be commended for this.

2.9

One of the notable examples we saw was Central Hawke's Bay District Council. The description of its most significant challenge – the historical underinvestment in its essential infrastructure – was clear and to the point. The Council also clearly set out its response, which was to significantly increase its investment in nearly every aspect of its services.

2.10

Central Hawke's Bay District Council also used graphics throughout its 2021-31 consultation document. Figure 1 shows how the Council described each of its "big challenges" using graphics.

Figure 1

How Central Hawke's Bay District Council used design to show its "big challenges" in its 2021-31 consultation document

Source: Central Hawke's Bay District Council, Facing the Facts: Consultation Document Long Term Plan 2021-31, page 7.

Addressing challenges will come at an increased cost to ratepayers

2.11

The main way councils responded to challenges was to increase their investment in their operations and infrastructure. For some councils, the increased investment was significant. For example, West Coast Regional Council proposed a 20% increase in 2021/22 operating expenditure compared to what was budgeted for in its 2020/21 annual plan. This increase was similar to that of other regional councils.

2.12

The need to invest more in core activities was the main reason many councils gave to support rates increases that were more than what had been previously signalled. Covid-19 also affected some proposed rates increases. See paragraphs 2.16 to 2.21 for more information.

2.13

Figure 2 sets out the average increase in proposed rates revenue6 that councils consulted on and compares that to what councils forecast in their 2018-28 long-term plans. The proposed rates increase is significantly higher than what councils had previously signalled, especially in 2021/22, 2022/23, and 2023/24.

Figure 2

Proposed average increase in rates revenue, as reported in 2021-31 consultation documents, compared to 2018-28 long-term plan forecasts

Source: Our analysis of the information provided by councils to support the 2021-31 consultation documents and the 2018-28 long-term plans.

2.14

Figure 3 shows the spread of increases in rates proposed by councils. Reflecting the larger average increase shown in Figure 2, most councils proposed to increase their rates by between 5% and 10% in 2021/22, 2022/23, and 2023/24. About 20% of councils proposed to increase their rates by more than 10% in 2021/22. From 2024/25, most councils' proposed rates increases were between 0% and 5%.

Figure 3

How many councils proposed to increase their rates for 2021/22 to 2030/31 and the percentage increase proposed

Source: Our analysis of the information provided by councils to support the 2021-31 consultation documents.

2.15

Our report on the audits of the 2021-31 long-term plans will further explore the effect of rates revenue forecast in the adopted long-term plans.

Explaining rates increases in the consultation documents

2.16

Information about rates and the increase faced by ratepayers is always of high public interest. These matters were discussed in several ways in the 2021-31 consultation documents. We considered that there were generally good links between the average rates increase and the reasons for those increases in the consultation documents.

2.17

However, some councils could improve how they explain what is causing the rates increase. One way could be to provide clear disclosure on increases to both the general rate and targeted rates in the consultation document. We saw instances where councils focused only on the general rate increase, and there was little or no discussion of the change in targeted rates proposed. Targeted rates can disproportionally affect some ratepayers. Without a clear explanation in the consultation document about how the targeted rates change, some ratepayers could be disadvantaged in their ability to engage with the council.

2.18

Most councils use the "sample rates information"7 contained in the consultation document to give individual ratepayers an indication of the size of the increase they will face in their rates. For this to work well, councils need to include all rates a ratepayer might face. We recognise that this can be challenging, particularly where councils have many different rates. Online rates calculators can be used to address this challenge (see paragraph 2.42).

Therefore, we encourage councils, when they are preparing their consultation documents, to take due care in ensuring that the proposed rates increases disclosed are accurate.

2.19

After South Wairarapa District Council adopted its 2021-31 long-term plan, the Council and our Office received correspondence from members of the community asking about the size of the 2021/22 rates increase. The rates being charged in rates invoices were significantly higher than what had been indicated in the South Wairarapa District Council's consultation document.

2.20

Like some other councils, South Wairarapa District Council provided rates relief by reducing the proposed increase in the 2020/21 rates because of concerns about the economic impact of Covid-19. This rates relief ended in 2021/22. However, the Council's consultation document did not clearly outline how the 2021/22 rates would be affected by the required catch-up. This was also not something that was identified as part of the audit. In response to the concerns raised, the Council published a statement to explain to its community what had happened and what it planned to do in response.

2.21

There is a high public interest in rates and rates increases. Therefore, we encourage councils, when they are preparing their consultation documents, to take due care in ensuring that the proposed rates increases disclosed are accurate.

The ongoing impact of Covid-19 on councils was limited

2.22

As outlined in paragraphs 1.24 to 1.25, Covid-19 indirectly affected many councils in developing their 2021-31 long-term plans. The 2021-31 consultation documents discussed the extended impact of Covid-19 on council operations and communities. We expected these types of disclosures as many communities would want to know how their council planned to support them in the recovery from Covid-19. We also expected interest in how councils planned to respond to long-term issues such as climate change, freshwater quality, and changing health standards. Communities will expect solutions that balance the recovery from Covid-19 with these long-term issues.

2.23

Most councils identified that, although the impact of Covid-19 on their wider community could be significant, the impact on the council operations was less significant. This was because the councils assumed there would be no further long-running lockdowns, and the borders would progressively open, signalling a return to more normal economic activity. These assumptions were consistent with forecasts from the Treasury that had been released as councils were developing their forecasts.

2.24

There were exceptions. Auckland Council described the challenges in achieving its objectives because it would receive $450 million less revenue in 2021 and cumulative reductions in revenue projected to reach about $1 billion by 2023/24. This reduced revenue meant the Council proposed to reprioritise some of its planned works.

2.25

In Rotorua Lakes Council's consultation document, one of the key priorities was economic development. Immediately after the March 2020 lockdown, Rotorua experienced the third largest economic drop in gross domestic product. Revenue within the tourism sector dropped by 40%. This compounded existing challenges like limited employment, low wages, undeveloped land, and a lack of appropriate infrastructure needed for commercial and industrial growth. The Council proposed several responses, including providing $29 million to support economic development and economic recovery projects.

2.26

As noted in paragraph 1.23, many councils reduced proposed rates increases to provide relief to those affected by Covid-19 lockdowns and restrictions. Where affected councils were unable to sustain the rates relief, their proposed higher rates increase in 2021/22 effectively reflected two years of rates increases.

Consultation documents are getting longer

2.27

A main challenge for councils preparing consultation documents is to present information in a concise and readable way. To do this well, councils need to achieve a balance between context and the issues being consulted on.

2.28

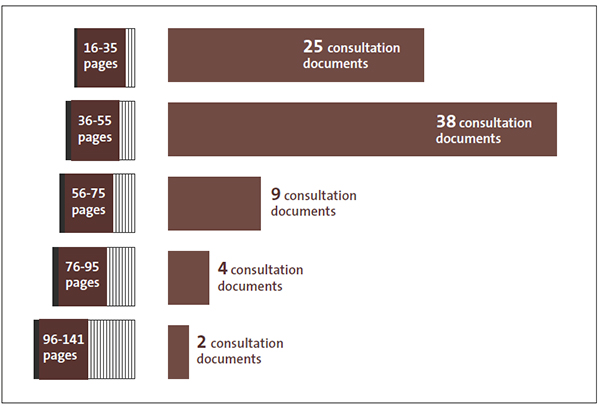

One factor we have considered in each of the last three long-term plan rounds is the length of consultation documents. The 2021-31 consultation documents ranged from 16 pages (Clutha and South Wairarapa District Councils) to 141 pages (Tauranga City Council). The average length of all consultation documents was 46 pages. Figure 4 gives more information on the length of consultation documents.

2.29

The 2018-28 consultation documents ranged from 16 pages to 90 pages, with an average length of 37 pages. For the 2015-25 consultation documents, the average length was 32 pages.

Figure 4

The length of councils' 2021-31 consultation documents

Source: Our analysis of the 2021-31 consultation documents.

2.30

Consultation documents are getting longer with each iteration. We are not surprised by this. We observed that councils were clearer in their consultation documents about the main challenges they and their communities were facing (see paragraphs 2.6 to 2.10). To do this well will generally mean a longer consultation document.

2.31

However, there is a risk that a longer consultation document will not be read or not read in full. A longer document only works well if the consultation documents are written in plain English and presented in a way that keeps the reader in mind. This is what we generally observed in the 2021-31 consultation documents.

We encourage councils to carefully consider the content and, where possible, remove less important material if they are developing a longer consultation document.

2.32

At 141 pages, Tauranga City Council had the longest consultation document. The Council used white space throughout the document, which made it uncluttered and easy to read. It also included what we considered were effective graphics, particularly in the early part of the document. There was also a lot of information about the six matters the Council was seeking community feedback on.

2.33

Despite that, the size of the Tauranga City Council's consultation document might have been daunting for some in the community to engage with. We encourage councils to carefully consider the content and, where possible, remove less important material if they are developing a longer consultation document.

2.34

In our view, clear messages, and the ability of the community to engage with them, are more important than the number of pages. Using infographics and a mix of text, tables, and diagrams can effectively convey key messages to the reader. A long document is also easier to read if it is structured logically, with a clear hierarchy of headings.

Different approaches councils took to encourage public participation

2.35

Councils are increasingly trying different approaches to better engage with their communities. By offering a range of ways for people to engage, it allows people to select the right tools for them to engage with the issues and carry out meaningful and responsive engagement with their Council. We discuss some notable examples in paragraphs 2.37 to 2.49.

We encourage other councils to consider whether they could also make use of these different approaches to create more public participation.

2.36

Few of the approaches below are new to this consultation document round.8 However, some are only being used by a small number of councils. We encourage other councils to consider whether they could also make use of these different approaches to create more public participation.

Early engagement

Early engagement

2.37

An increasing number of councils are engaging with their communities early. This approach helps a council to understand what is important to their community, which then informs the development of the consultation document and long-term plan.

2.38

Northland Regional Council had a series of pop-up stalls at various community events and used an online feedback portal to gather responses in 2020, ahead of developing proposals for its long-term plan.

Dedicated webpages

Dedicated webpages

2.39

Many councils make use of dedicated webpages when consulting with their communities. This approach means that people have a "one-stop shop" to obtain further information.

2.40

In our view, Wellington City Council had an effective consultation website. Videos explained the Council's priorities and the process. Each of the Council's "big decisions"9 was set up as a separate webpage. As well as including almost all relevant information about each decision, the Council also allowed members of the community to ask questions through these webpages. The Council included both the questions and the answers on the webpage for others to view.

2.41

Although we can see the benefits of Wellington City Council's approach, we also saw some drawbacks. Someone could submit on the long-term plan through the webpages without reading the full consultation document. As well as not considering the whole document, they might have also missed that our audit report included qualifications where we disagreed with the quality of the information and assumptions that the Council used to inform the consultation document (see paragraphs 5.44, 5.48, and 5.49). We recognise that an individual would have to read 72 pages of the full consultation document before coming to the audit report.

Online rates calculators

Online rates calculators

2.42

Some councils had an online rates calculator that ratepayers could use to assess how key proposals would affect their rates before giving feedback on proposals. This complemented the sample rates information we describe in paragraph 2.18.

2.43

This approach meant that ratepayers had specific information on how a council's proposal would affect them. Some councils – including Auckland Council, Hamilton City Council, and Tauranga City Council – also offered an online rates calculator when preparing their 2018-28 long-term plans.

Social media

Social media

2.44

Some councils used social media to engage with their communities. For example, Napier City Council and Rangitīkei District Council used Facebook's "live sessions" to connect with those in their communities that prefer to engage online.

2.45

Auckland Council and Hamilton City Council were among the councils that asked for feedback through comments on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

2.46

Generally, councils made it clear that feedback received through social media channels would not be considered a formal submission. This might discourage people from engaging.

Accessibility considerations

Accessibility considerations

2.47

As with preparing its 2018-28 long-term plan, Auckland Council ensured that its diverse communities could engage with its 2021-31 consultation document. The Council provided videos, documents, and feedback forms that were translated into te reo Māori, simplified Chinese, Korean, Fa'asamoa, Faka-Tonga, and New Zealand Sign Language.

2.48

Dunedin City Council posted a video of someone reading the consultation document in its entirety for someone to listen to. Northland Regional Council advised that if members of the community wanted to provide feedback in te reo Māori or New Zealand Sign Language, they could do so at its scheduled events.

2.49

Environment Canterbury accepted video feedback, which could be uploaded through the online submission process.

A time to review the legislative requirements

2.50

In Part 1, we discussed the legislative requirement of consultation documents in the Local Government Act 2002. The intent of introducing consultation documents was to improve council engagement with communities over the content of long-term plans. Councils have now produced audited consultation documents for three long-term plan cycles.

2.51

In our view, councils are producing consultation documents that are more engaging than the summary of the draft long-term plans that councils produced before 2015.

2.52

Although councils are free to decide what to put in their consultation documents to meet the Act's requirements, there are some mandatory requirements (as outlined in section 93C of the Act). We have heard from some councils that including the mandatory requirements can often be a compliance exercise and these are not considered to add value to the consultation document. Including additional information can also add to the length of the document, which increases the risk that the document will not be read.

2.53

There has also been a lot of change in the ways that councils choose to engage with their communities. Increasingly, councils are not using the document to engage with their communities but are instead increasingly using online channels. As we noted in paragraph 2.41, people can submit on the long-term plan without reading the full consultation document that is meant to be the basis of that engagement. This indicates that the legislation might be starting to fall behind current engagement practices.

| Recommendation |

|---|

| We recommend that the Department of Internal Affairs and the local government sector review the consultation requirements for long-term plans to ensure that the engagement process and content requirements of a consultation document remain fit for purpose. |

4: See Office of the Auditor-General (2018), Long-term plans: Our audits of councils' Consultation documents, Part 2.

5: We note we issued an adverse audit opinion on Palmerston North City Council's consultation document. We comment on this further in paragraphs 5.15 to 5.20.

6: In this paragraph and in Figure 2, the average increase in rates revenue has been calculated as the average of all the councils' individual increase in rates revenue.

7: Councils are required to disclose in their consultation document examples of the impact of the proposals on the rates. This disclosure should cover different categories of rateable land (for example, residential, industrial, commercial, or rural properties) and with a range of property values.

8: See Office of the Auditor-General (2018), Long-term plans: Our audits of councils' Consultation documents, Part 3.

9: This is how Wellington City Council defined the consultation issues it wanted specific feedback on.