Part 3: The Controller function

3.1

The Controller function is an important part of the Auditor-General's work. It supports the fundamental principle of Parliamentary control over government expenditure.

3.2

Under the country's constitutional and legal system, the Government needs Parliament's approval to:

- make laws;

- impose taxes on people to raise public funds;

- borrow money; and

- spend public money.2

3.3

Parliament's approval to incur expenditure is mainly provided through appropriations,3 which are authorised in advance through the annual Budget process and annual Acts of Parliament. When the Government wants to incur expenditure not yet authorised in an Appropriation Act, it can draw on the Parliamentary authority provided in an Imprest Supply Act. Expenditure can be authorised in advance through permanent legislation. Some expenditure can also be approved retrospectively.

3.4

In 2020/21, there was a significant decrease in the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure. The Government's financial statements report 12 instances for 2020/21, which is the lowest occurrence of unappropriated expenditure so far this century.4

3.5

In this Part, we discuss:

- why the Controller work is important;

- how much public expenditure was unappropriated in 2020/21;

- why the expenditure was unappropriated;

- how 2020/21 compared with previous years; and

- a summary of work we carried out in 2020/21 to discharge the Controller function.

Why the Controller work is important

3.6

Appropriations ensure that Parliament, on behalf of the public, has adequate control over how the Government plans to spend public money. It also ensures that the Government can be held to account for how it has used that money.

3.7

Most of the Crown's funding is obtained through taxes. The public is entitled to assurance that the Government is spending public money as authorised by Parliament.

3.8

As the Controller, the Auditor-General helps maintain the transparency and legitimacy of the public finance system. The Auditor-General provides an important check on the system on behalf of Parliament and the public by providing independent assurance that the spending is within authority. The Auditor-General also provides assurance that any government spending without authority has been identified and dealt with appropriately. As an Officer of Parliament, the Auditor-General is independent of the Government.

3.9

In the Appendix, we explain how public expenditure is authorised, who is responsible for managing it, and the Controller's role in checking it.

How much public expenditure was unappropriated in 2020/21?

3.10

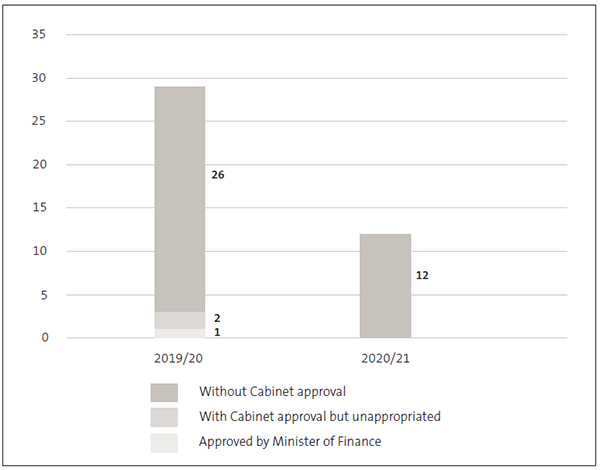

The Government's financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2021 report 12 instances of unappropriated expenditure (2019/20: 29). Expenditure incurred above or beyond appropriation for the 2020/21 year was $133 million (2019/20: $925 million). Figure 1 shows a breakdown of unappropriated expenditure categories.5

Figure 1

Unappropriated expenditure incurred for the year ended 30 June 2021

| Category | Unappropriated expenditure by category | 2020/21 Number | 2020/21 $million* | 2020/21 Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act 1989. | - | - | |

| B | With Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but in excess of appropriation prior to the end of the financial year. | - | - | |

| C | With Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but without appropriation prior to the end of the financial year. | - | - | |

| D | In excess of appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 5 | 82 | Defence Force, Internal Affairs |

| E | Outside scope of an appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 3 | 15 | Business, Science and Innovation; Education; Revenue |

| F | Without appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 4 | 36 | Arts, Culture and Heritage; Business, Science and Innovation; Housing and Urban Development; Tertiary Education |

| Total | 12 | 133 |

* Amounts are rounded to the nearest million.

3.11

The unappropriated expenditure categories shown in Figure 1 fall into three broader categories:

- Approved by the Minister of Finance (Category A): Small overruns of expenditure in the last three months of the financial year (that is, within $10,000 or 2% of the appropriation) may be approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act. Although unappropriated, expenditure approved under section 26B is lawful.

No instances of unappropriated expenditure were recorded under this section for 2020/21 (2019/20: one instance). - With Cabinet approval (Categories B and C): When it is anticipated that expenditure will be incurred above or beyond the appropriation limits, departments should seek prior Cabinet approval to use imprest supply for the spending not covered by appropriations. Sometimes Cabinet's approval to use imprest supply is obtained, but the extra spending is not included in an Appropriation Act before the end of the financial year, so the spending remains unappropriated.

There was no expenditure in this category in 2020/21, meaning that every dollar of expenditure authorised under imprest supply in 2020/21 was subsequently appropriated through the Supplementary Estimates Act (2019/20: two instances). - Without prior Cabinet approval (Categories D, E, and F): For 2020/21, the Government's financial statements report 12 instances of expenditure incurred above or beyond the appropriation limits without any authority at the time it was incurred, that is, without Parliamentary appropriation and without Cabinet's prior approval to use imprest supply (2019/20: 26 instances).

3.12

Figure 2 shows the considerable decrease in the reported instances of unappropriated expenditure in 2020/21 compared with 2019/20. Instances of expenditure without prior Cabinet approval were less than half that for the previous year.6

Figure 2

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2021

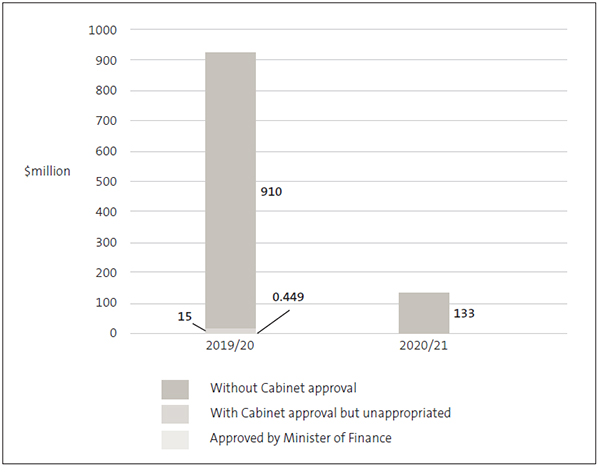

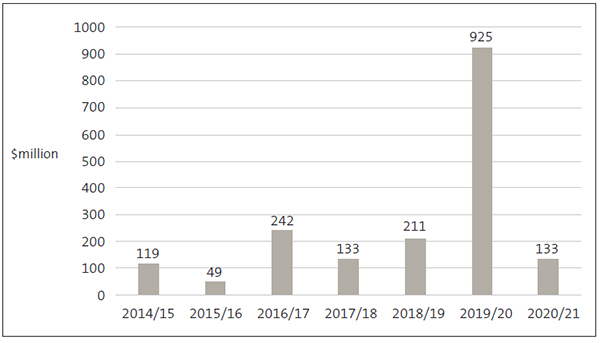

3.13

Figure 3 compares the dollar amounts of unappropriated expenditure for 2019/20 and 2020/21. The amount of unappropriated expenditure decreased from just over $925 million for 2019/20 to $133 million for 2020/21 although, as shown in Figure 6, 2019/20 was an outlier compared with recent years.7

Figure 3

Amount of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2021

3.14

Expenditure outside the bounds of the appropriations tends to be relatively low. Unappropriated expenditure of $133 million for 2020/21 was 0.09% of the Government's final budgeted amount for that year, compared with 0.61% in 2019/20.

Why was the expenditure unappropriated?

3.15

Of the $133 million of expenditure unappropriated in 2020/21, almost all was due to the following reasons:

- 61% by value was because of departments not adjusting to changes in customer entitlements;

- 23% by value was because of administrative errors; and

- 10% by value was because a public organisation changed its operations to an activity not covered by its appropriation.

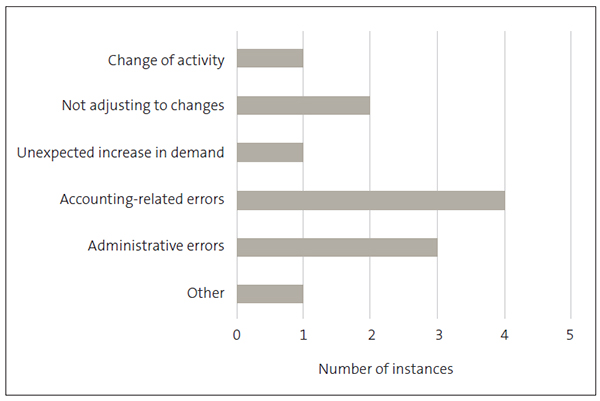

3.16

Figure 4 assigns the instances of unappropriated expenditure into six categories that describe why the unappropriated expenditure came about. The most common reasons were accounting-related errors (four instances) and administrative errors (three instances).

Figure 4

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure in 2020/21, by number of instances

Change of activity

3.17

During the first Covid-19 lockdown, the Minister of Tourism endorsed Tourism New Zealand redirecting its efforts from marketing New Zealand overseas to promoting tourism to the domestic market. This was in response to the effect of the pandemic on global tourism and, specifically, the sudden halt in overseas tourists visiting New Zealand. Tourism New Zealand used its resources to promote New Zealand to New Zealanders through a "Do Something New, New Zealand" campaign. The campaign's intention was to stimulate tourism and therefore support the domestic tourism industry.

3.18

Parliament had authorised the funding of Tourism New Zealand's activities through an appropriation in Vote Business, Science and Innovation that is "limited to the promotion of New Zealand as a visitor destination in key overseas markets". Promoting tourism to the domestic market was outside the scope of what Parliament had approved.

3.19

Approval to change the scope of the appropriation was not sought before Tourism New Zealand embarked on its domestic marketing. As a result, a little over $2 million of spending was unappropriated in 2019/20 and a further $13.5 million was unappropriated in 2020/21, before the correct authority was put in place in December 2020.8

Not adjusting to changes

3.20

In two instances, government departments did not seek adjustments to their appropriations in time for implementing changes to customer entitlements.

3.21

In 2020/21, the Defence veterans' entitlement for qualifying service was widened. The Government's decision and announcement led to an increase in the Veterans' Entitlements obligation and a commensurate expense increase. This resulted in expenses exceeding appropriation in Vote Defence Force by $78.9 million.

3.22

The Parental Leave and Employment Protect Act 1987 was amended during 2016. Amendments included changes to the entitlement criteria for recipients who had more than one employer. From April 2016 to February 2021, the calculations for some recipients were incorrect and, accordingly, some payments were incorrectly made. This resulted in $1.5 million of unappropriated expenditure for Vote Revenue in 2020/21. We have also confirmed the amount of unappropriated expenditure for each year from 2015/16. The Government will seek validation for each year's unappropriated expenditure through the next Appropriation (Confirmation and Validation) Act.

Unexpected increase in demand

3.23

The Department of Internal Affairs administers rates rebates for low-income ratepayers, under the Rates Rebates Act 1973. The demand for rebates under the scheme exceeded the Department's forecast for 2020/21, resulting in expenses exceeding the appropriation in Vote Internal Affairs by $1.6 million.

Accounting-related errors

3.24

Two departments had not sought appropriation to authorise the expenses that arose from writing down their loan values.

3.25

During 2019/20, in response to the economic effects of Covid-19, the Government decided to pay local media businesses in advance to run advertisements in 2020/21. Because the advanced payments were interest free, they needed to be accounted for as concessionary loans. As a result, the carrying value of the loans had to be written down to reflect their fair value. The Ministry for Culture and Heritage charged the expense ($121,000 for 2019/20 and $47,000 for 2020/21) against the Grants and Subsidies appropriation category, the scope of which does not authorise this type of expense.

3.26

In a similar case, the Energy Efficiency & Conservation Authority (EECA) administers the Crown Energy Efficiency Loan Scheme, which assists public organisations to implement energy efficiency and carbon emission reducing projects. The loans are funded through Vote Business, Science and Innovation, which is administered by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. The loan principal is repaid by third parties through EECA to the Ministry.

3.27

Because the loans are provided at below market interest rates, they need to be accounted for as concessionary loans. As such, the carrying value of the loans needed to be written down to reflect their fair value. The Ministry did not have an appropriation against which to charge the write-down expense of $37,000 for 2020/21.

3.28

We have also confirmed unappropriated expenses relating to write-downs for the five previous years for loans under this Loan Scheme. The Government will seek validation for each year's unappropriated expenditure through the next Appropriation (Confirmation and Validation) Act.

3.29

The Department of Internal Affairs incurred expenditure of $28,000 on a grant in 2019/20 but accounted for it in 2020/21, when the amount was not covered by the appropriation.

3.30

Unappropriated expenditure was confirmed in earlier years under Vote Education. The School Support Project appropriation authorises (non-property related) capital expenditure on school support and improvement projects. The Ministry of Education identified that some historical expenditure was recognised as being operating in nature, as opposed to capital, and was therefore outside the scope of the appropriation. We have confirmed unappropriated expenditure between 2016 to 2019, which will require validation through the next Appropriation (Confirmation and Validation) Act. There was no operating expenditure recorded against this appropriation in 2019/20 or 2020/21.

Administrative errors

3.31

Two departments incurred unappropriated expenditure because they did not properly manage the arrangements needed to seek additional authority for expenditure that was nonetheless anticipated.

3.32

The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Historical Abuse in State Care and in the Care of Faith-based Institutions required additional funding under Vote Internal Affairs to continue its work in 2020/21. The risk of costs exceeding appropriation was identified, but the Department of Internal Affairs did not secure the approvals for increased funding early enough. This led to expenses exceeding appropriation on two occasions during 2020/21: $638,000 in late 2020 and $331,000 in early 2021.

3.33

On 17 February 2021, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development purchased land at Te Puke Tāpapatanga a Hape (commonly referred to as Ihumātao). To ensure that there was correct authority for the expenditure, the Ministry asked the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Housing to approve setting up a new appropriation, Te Puke Tāpapatanga a Hape (Ihumātao), within Vote Housing and Urban Development. This was agreed on 9 February 2021.

3.34

Newly set up appropriations do not have any legal authority until they are appropriated by Parliament through inclusion in an Appropriation Act. The soonest opportunity was provided through the Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates 2020/21) Act 2021, scheduled for June 2021. In the interim, the only authority available to the Ministry on 17 February 2021 was under the Imprest Supply Act.9 Due to an administrative oversight, the Ministry did not request Joint Ministers to approve the use of imprest supply for the purchase, in advance of receiving the appropriation through the Supplementary Estimates Act. As a result, the purchase price of $29.9 million was unappropriated expenditure.

Other

3.35

Tertiary education institutions (TEIs) can effectively own land and buildings, although the title to the land is with the Crown (this is known as "beneficial ownership"). On disposal, the standard arrangement is that the sale proceeds are repaid to the Crown and, under some circumstances, some or all of the sale proceeds may be returned to the TEI .

3.36

When a TEI retains the sale proceeds, it amounts to an equity injection from the Crown to the TEI, and that must be authorised through a capital expenditure appropriation in Vote Tertiary Education. Historically, some TEIs have retained the proceeds without the Ministry of Education having secured appropriation authority for the equity injection. This has resulted in unappropriated expenditure of $6.1 million for 2020/21. The Ministry identified the problem during 2020/21 and changed its approach to managing such sale proceeds to help prevent a recurrence. In March 2021 it gained approval under imprest supply to correctly authorise further expenditure of this nature in the 2020/21 year, as well as approval to establish a new appropriation to cover such expenditure in future. We have also confirmed unappropriated expenditure back to 2016/17.

How does 2020/21 compare with previous years?

3.37

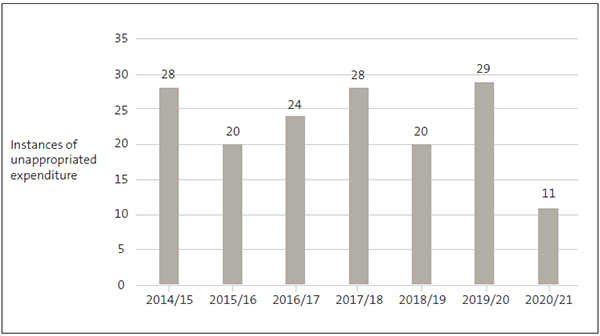

There was a significant decrease in the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure in 2020/21. The Government's financial statements for the year ended 30 June 2021 report 12 instances of unappropriated expenditure, and 11 of them were incurred during 2020/21 – the lowest number of occurrences at least as far back as the year ended 30 June 2000.

3.38

Figure 5 shows that the frequency of instances fluctuated between 20 and 29 for six of the last seven years, with a major dip in 2020/21.10

Figure 5

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure, from 2014/15 to 2020/21

3.39

Figure 6 shows the dollar amount of unappropriated expenditure incurred during the last seven years. Last year, 2019/20, was an outlier, mostly attributable to one instance of excess expenditure ($676.8 million) incurred due to an administrative error. The value of unappropriated expenditure returned to the familiar, fluctuating pattern in 2020/21.

Figure 6

Amount of unappropriated expenditure, from 2014/15 to 2020/21

Work carried out to discharge the Controller function

3.40

During the year, we carried out our core Controller work through our regular monitoring (with the Treasury) of expenditure against appropriations.11 Other core Controller activity involves our audits of appropriations and audits of the Government's financial statements and of individual government departments.12

3.41

We periodically published website reports on observations and findings from our monitoring of government expenditure, including a half-year report on expenditure against appropriations and three reports during 2020/21 on the Government's Covid-19 expenditure. Since 30 June 2021, we have published a website report on how changes are made and approved to the Government's budget between the annual Budgets, how they are scrutinised and authorised through the Supplementary Estimates, and the Controller and Auditor-General's role in monitoring these approvals.

3.42

One of the major objectives of the Controller function is to support Parliament in its exercising of control over the public purse. As part of this, we have continued to monitor the Government's "consolidation" of appropriations in Budget 2021, whereby it sought to combine separate appropriations into fewer, larger appropriations. We have observed that these changes have introduced more efficiency and flexibility in the authorising of public expenditure. We are supportive of such reforms so long as the transparency of, and accountability for, public spending is not unduly diminished, and Parliament's control of the public purse is not eroded.

3.43

During 2020/21, we worked with the Treasury on the question of whether the salary costs of seconded employees are properly authorised when the salary costs continue to be paid by the employee's home department. The question arises because all expenses incurred by a government department must be authorised by an appropriation that covers the activity undertaken. This important principle needs to be upheld to ensure that public money is not redirected away from the purposes that Parliament has authorised.

3.44

Covid-19 has highlighted this issue because many staff have been redeployed to support the Government's response. A potential problem arises when the home department continues to pay the salary of the secondee because the secondee's activities are likely to be outside the scope of the home department appropriations. This creates a risk of the home department incurring unappropriated expenditure.

3.45

We supported the Treasury in its development of guidance to government departments on the accounting and appropriation treatment of the salary costs of seconded staff. The Treasury guidance was issued in May 2021.

3.46

Through the Treasury's Finance Development Programme, we were given the opportunity to discuss with government department finance professionals the importance of Parliamentary control of Crown spending and how the Controller function supports New Zealand's constitutional arrangements. We highlighted:

- why it is important to avoid incurring public expenditure without the proper authority;

- what some of the more common pitfalls are that lead to unappropriated expenditure; and

- how government departments can avoid it.

2: Section 22 of the Constitution Act 1986.

3: Appropriations are authorities from Parliament that specify what the Crown may incur expenditure on (specific areas of expenditure). Most appropriations specify limits in terms of the type of expenditure (the nature of the spending), scope (what the money can be used for), dollar amount (the maximum that can be spent), and period (the time frame for which the authority is given).

4: We have surveyed the Government's financial statements for each year, as far back as the statements for the year ended 30 June 2000.

5: New Zealand Government (2021), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2021, Wellington, pages 143-149.

6: New Zealand Government (2021), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2021, Wellington. One of the 12 instances recorded for 2020/21 relates to unappropriated expenditure incurred in earlier years that was identified, but not incurred, in 2020/21.

7: New Zealand Government (2021), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2021, Wellington.

8: We first reported on this matter in March 2021, in our half-year Controller Update, Controller update: July to December 2020.

9: Imprest Supply (Second for 2020/21) Act 2020.

10: Figure 5 shows instances of unappropriated expenditure allocated to the financial year to which they relate.

11: Under section 65Y of the Public Finance Act 1989.

12: Under section 15 of the Public Audit Act 2001.