Part 1: How councils responded to forecast infrastructure investment

1.1

In this Part, we discuss how well councils reinvested in their assets, built assets needed for growth, and delivered on their 2018/19 capital expenditure budgets.

1.2

The main trend we identified in councils' financial forecasts in their 2018-28 long-term plans (LTPs)1 was that councils were planning to invest in their assets at levels not seen before. To have a realistic chance of achieving their capital expenditure programme budgets, we said that councils needed to carefully plan, prioritise, and monitor their budgets.

1.3

Councils are required to disclose their capital expenditure in three categories:

- replacing or renewing assets;

- building new assets to meet additional demand; and

- improving service levels.

1.4

Most of the planned capital expenditure in councils' 2018-28 LTPs was to replace or renew council assets. However, this expenditure was less than the forecast depreciation charge for the 10-year period. This indicated to us that, as a whole, councils did not appear to be forecasting to adequately reinvest in their assets. We said that this could result in the quality of their assets deteriorating.

1.5

If councils continue to underinvest in their assets, the cost of reinvestment to reinstate the service potential of existing assets might fall on future generations. We have been concerned about this for some time.

1.6

We also identified that "high-growth"2 councils had challenges to address, including how they would fund the planned capital expenditure.

1.7

Therefore, we analysed councils' financial information to see what happened in 2018/19, the first year of the 2018-28 LTP period. Specifically, we asked:

- How well are councils reinvesting in their assets?

- How well did councils build the assets they need for ongoing growth?

- How well are councils delivering on their capital expenditure budgets?

How we carried out our analysis

1.8

To carry out our analysis, we considered the local government sector both as a whole and as five sub-sectors. The sub-sectors were:

- metropolitan councils;

- Auckland Council (considered separately from other metropolitan councils because of its size);

- provincial councils;

- regional councils; and

- rural councils.

1.9

See Appendix 2 for more information on the sub-sectors.

How well are councils reinvesting in their assets?

1.10

To consider how well councils are reinvesting in their assets, we compared capital expenditure on renewals with depreciation. We consider depreciation to be the best estimate of the portion of the asset that was "used up" during the financial year.

1.11

Overall, we remain concerned that councils might not be adequately reinvesting in critical assets. If councils continue to underinvest in their assets, there is a risk of reduced service levels, which will negatively affect community well-being.

1.12

In 2018/19, all councils' renewal capital expenditure was 79% of depreciation. This means that, for every $1 of assets used up, councils were reinvesting only 79 cents. This percentage was less than the 91% that all councils planned for in their 2018-28 LTPs. For 29 councils, renewal capital expenditure was more than 100% of depreciation, which is the highest number in the last seven years. The majority of these councils had budgeted to spend more than 100% of depreciation on renewal capital expenditure.

1.13

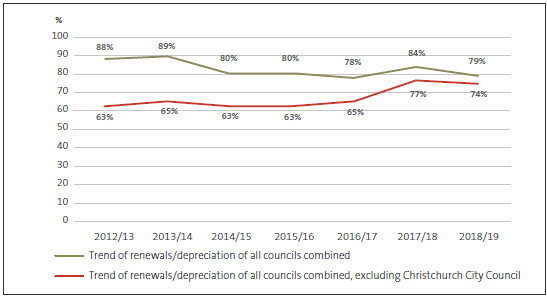

Figure 1 compares renewal capital expenditure with depreciation for all councils, from 2012/13 to 2018/19. There are two lines on the graph. The green line includes all councils. The red line excludes Christchurch City Council.

1.14

Christchurch City Council's renewal capital expenditure is proportionately higher than other councils because of the rebuilding work it has done since the 2011 Canterbury earthquakes.

1.15

During the past seven years, renewals ranged between 78% and 89% of depreciation for all councils. The effect of Christchurch City Council's rebuild effort after the Canterbury earthquakes did not give a true picture of how much all councils were investing in renewals, mainly from 2012/13 to 2016/17. We have seen a significant improvement in other councils' renewal investment from 2016/17.

Figure 1

Renewal capital expenditure compared with depreciation for all councils, 2012/13 to 2018/19

There are two lines on the graph. The green line includes all councils, and the red line excludes Christchurch City Council. Both lines show that renewal capital expenditure is less than depreciation for the period from 2012/13 to 2018/19, although there has been a significant improvement in councils' renewal efforts since 2016/17.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

1.16

When considering council sub-sectors, and excluding Christchurch City Council, two sub-sectors have a different trend to the red line in Figure 1:

- Regional councils' renewals as a percentage of depreciation ranged from 74% (in 2012/13) to 170% (in 2018/19). Greater Wellington Regional Council replacing a significant amount of public passenger vehicles during 2018/19 heavily influenced that year's figure.

- Rural councils' renewals as a percentage of depreciation ranged from 75% (in 2016/17) to 98% (in 2018/19). Rural councils' roading assets are rural councils' largest asset category. A central government subsidy through the New Zealand Transport Agency (NZTA) partly funds these assets. The funding from NZTA gives councils an incentive to replace their roading assets. This funding relationship might explain why they have a different trend to other councils.

1.17

Several factors could be contributing to the gap between renewals and depreciation, which might partially explain the apparent underinvestment in assets. For example, depreciation could be overestimated (because councils have not reviewed and adjusted the remaining useful lives of assets), or there could be changes in prices associated with asset renewal work over time. We discuss the importance of accurate depreciation expense estimates below.

1.18

In our view, each council needs to consider the robustness of the renewals gap in its context and the funding implications arising to ensure that there is adequate financial provision for renewing assets in the future.

1.19

To do this well, councils need to improve their asset management information. In particular, they need:

- good data about their critical assets in order to value, depreciate, and plan renewals;

- good processes and sufficient resources to maintain and update their critical asset data;

- effective working relationships between asset management, finance, and strategic planning staff, all of whom have an important role to play in supporting a council's asset management function; and

- timely engagement with, and involvement by, elected members.

1.20

We provide a good practice example of a council that prioritised collecting better condition and performance information for their assets in Part 2.

1.21

We will continue to encourage councils to prioritise reinvesting in their assets and being transparent with their communities about the condition of council assets and reinvestment strategies.

How councils can improve the reasonableness of the depreciation expense

1.22

Depreciation is a major expense for all councils. It reflects the progressive using up of an asset during its useful life. In 2018/19, depreciation across the local government sector amounted to $2.52 billion.

1.23

Although depreciation is a non-cash cost, it has economic substance. It reflects that assets deteriorate through use and need to be periodically replaced. It is important for councils to ask whether the assessed depreciation charges are reasonable, given the age and condition of their assets.

1.24

Not having a reasonable depreciation expense has some significant risks for a council. For example, the amount of revenue a council collects to renew its assets might exceed or fall short of what is required. Because many councils use rates revenue to fund the renewal of assets, this could mean that councils are collecting too much rates revenue or not enough.

1.25

The reasonableness of depreciation relates to the assumptions used and how they compare to industry expectations, councils' understanding of their assets data (including the condition and performance of critical assets), and the strength of the asset valuation process. Good assumptions to support the depreciation expense is needed for councils to make good decisions about the renewal of their assets.

1.26

We are aware that some valuers are becoming concerned about the quality of councils' asset valuations. In our view, the main valuation challenges that need to be addressed are:

- understanding what an asset's "useful life" is;

- regularly reviewing asset useful lives;

- being over-reliant on asset useful lives that have not been properly assessed for the council's situation;

- collecting enough asset condition and performance data;

- weak records about the cost of asset renewals;

- actively considering new asset replacement techniques;

- ensuring that council staff who rely on valuation information are involved early in the valuation process so the valuation meets everyone's needs; and

- the industry guidance developed by the Institute of Public Works Engineering Australasia that councils use to inform asset valuations is updated.

1.27

We discuss these valuation challenges in Appendix 4. We encourage councils' audit and risk committees to discuss with council staff how their council is considering and addressing these challenges.

1.28

Using their financial strategies and revenue and financing policies, councils will need to assess the extent to which they will fund depreciation through revenue sources such as rates. The Local Government Act 2002 requires councils to be financially prudent. It is far more difficult for a council to demonstrate financial prudence if it does not fully fund its depreciation expense through revenue sources.

1.29

We are concerned that councils are not paying enough attention to assessing the appropriate depreciation expense in conjunction with its periodic valuation of its assets. Some useful steps a council could take to improve the quality of its asset valuations, and therefore the reasonableness of its depreciation expense, are:

- having better processes to identify and plan for when a valuation is required – all relevant parties, including the valuer and the council's finance and asset management staff, should be involved in this process to ensure that all aspects are considered;

- treating the valuation process as a project and using good project management principles;

- incorporating the valuer's suggestions for improvement into work programmes; and

- appropriately measuring work on the improvement areas identified in a valuation process and formally reporting progress to its audit and risk committee.

1.30

Having a more accurate depreciation expense will help inform councils of the right amount of reinvestment their assets need over the medium to long term to continue to deliver services to the community. It will also give councils a better understanding of the current costs of delivering those services.

How well did councils build assets needed for ongoing growth?

1.31

This is the first year we have examined how well councils experiencing population growth have achieved their growth-related capital budgets. We found that most councils did not build all the assets they budgeted for in 2018/19. These councils will need to reassess their future planned budgets to accommodate what was not achieved in 2018/19. We will continue to keep an eye on their performance.

1.32

Some councils are experiencing significant population growth. These councils have been defined as "high-growth" councils under the National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity.3 In their 2018-28 LTPs, high-growth councils forecast making significant investments to meet the additional demand on their infrastructure.

1.33

In 2018/19, high-growth councils spent about $0.93 billion on capital expenditure intended to meet additional demand. This was about 64% of the $1.46 billion budgeted for this purpose. Two councils, Christchurch and Tauranga City Councils, spent more than their growth-related capital expenditure budgets. In contrast, Selwyn and Western Bay of Plenty District Councils spent less than 40% of their budgets.

1.34

In their annual reports, high-growth councils said that delays and "timing differences" in projects were the main reasons why they did not meet their growth-related capital expenditure budgets. The main reason Christchurch and Tauranga City Councils spent more than their budgets was because they brought growth-related projects forward and completed them earlier in 2018/19.

1.35

High-growth councils did not cite funding concerns as a reason why they did not complete their growth-related capital expenditure. High-growth councils received capital subsidies or grant revenue of $0.46 billion – 26% less than the $0.62 billion budgeted. This decrease appears to be because councils had not started projects, rather than the funding not being available to allow projects to begin.

1.36

Non-council development still occurs in high-growth council areas. In 2018/19, third parties (mainly developers) gifted4 $0.76 billion of assets to high-growth councils to manage and maintain in the future. This was about 46% more than the $0.52 billion budgeted.

How well are councils delivering on their capital expenditure budgets?

1.37

Most councils did not deliver on their capital expenditure budgets.

1.38

Councils' total capital expenditure in 2018/19 was $4.66 billion, which was the highest amount councils spent on their assets in the last seven years. However, the amount spent was only about 82% of the $5.70 billion budgeted.5 This is a smaller percentage than in 2017/18, when councils spent 84% of their capital expenditure budgets.

1.39

Project delays or deferrals were the most common reasons given by councils that spent significantly below their capital expenditure budgets. These delays were caused by several matters, including reprioritisation of council projects, internal delays (such as consenting issues), and contractual delays (such as tender processes taking longer than expected).

1.40

On average, all council sub-sectors spent less than 100% of their capital expenditure budgets. The regional council sub-sector was the lowest, spending $175 million or, on average, 66% of their budget. By comparison, Auckland Council spent $1.90 billion or 89% of its budget.

1.41

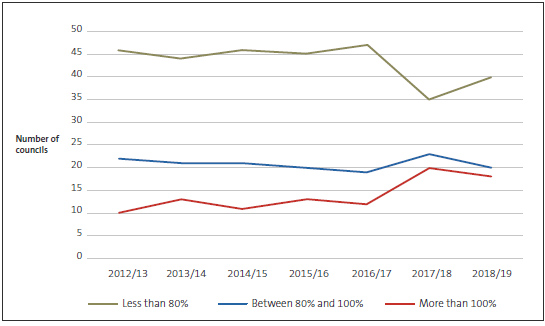

Looking at individual councils, 40 councils spent less than 80% of their capital expenditure budgets. This continues a trend we have observed over time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

How much councils spent of their budgeted capital expenditure, 2012/13 to 2018/19

In 2018/19, 40 councils spent less than 80% of their capital expenditure budgets. This was five more councils than in 2017/18, although it was less than in the other years. Councils spending more than 100% of their budget remained the smallest category.

Source: Analysed from information collected from councils' annual reports.

1.42

Most councils fund some of their capital expenditure through debt. As at 30 June 2019, councils' total debt was $17.1 billion, which was $1.0 billion more than at 30 June 2018. Councils had budgeted to have $17.7 billion of debt at 30 June 2019. However, councils did not need all of this debt because they did not spend all of their capital expenditure budgets.

1.43

In our report on councils' 2018-28 LTPs, we considered that councils would need to carefully plan, prioritise, and monitor their capital programme budgets to have a realistic chance of achieving them.6 After looking at their 2018/19 performance, our views have not changed.

1.44

Councils will soon be preparing their 2021-31 LTPs. During this process, councils should consider how achievable their capital expenditure forecasts are. We encourage councils to consider:

- their previous delivery of capital expenditure budgets;

- their, and the local contracting industry's, capability and capacity to deliver the proposed capital expenditure budgets; and

- other planning needs, such as consent requirements.

1.45

Recently, the Government set up the New Zealand Infrastructure Commission – Te Waihanga. The Commission seeks to improve infrastructure planning and delivery. By doing so, it hopes to improve New Zealanders' long-term economic performance and social well-being.

1.46

One area of focus for the Commission is creating an infrastructure "pipeline"7 that will be built up over time. The pipeline will give the market more visibility and more certainty about future projects to help suppliers plan and prepare. We encourage all councils to engage with the Commission so that it can begin including their future projects in the pipeline.

1.47

The Commission also provides procurement and delivery advice and support. We encourage councils to investigate how the Commission can support them.

1: Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans, Wellington.

2: High-growth councils are defined under the National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity. See also Appendix 2.

3: See Appendix 2 for more information about which councils are defined as high-growth.

4: Gifted assets are called "vested assets" in councils' statement of comprehensive revenue and expense statements. They are a type of non-cash revenue. Typically they are roads or pipes connecting properties to the council's networks.

5: This information is from the statement of cash flows of councils. It includes only the cash that councils spent on purchasing property, plant, and equipment and intangible assets.

6: Office of the Auditor-General (2019), Matters arising from our audits of the 2018-28 long-term plans, Wellington, paragraph 3.29.

7: The pipeline is a list of intended infrastructure projects provided by central and local government organisations and the private sector.