Part 3: The Controller function

3.1

The Controller function is an important part of the Auditor-General's work. It supports the fundamental principle of Parliamentary control over government expenditure.

3.2

The importance of this function is reinforced by the current increased levels of government spending for the Covid-19 response. Since March 2020, the Controller function has focused on Covid-related expenditure because of the significant funding available for responding to Covid-19 and the long-term implications of this expenditure.

3.3

Under the country's constitutional and legal system, the Government needs Parliament's approval to:

- make laws;

- impose taxes on people to raise public funds;

- borrow money; and

- spend public money.2

3.4

Parliament's approval to incur expenditure is mainly provided through appropriations,3 which are authorised in advance through the annual Budget process and annual Acts of Parliament. When the Government wants to incur expenditure not yet authorised in an Appropriation Act, it can draw on the Parliamentary authority provided in an Imprest Supply Act. Expenditure can be authorised in advance through permanent legislation. Expenditure can also be validated retrospectively.

3.5

In 2019/20, the Government incurred a large amount of expenditure without Parliament's authority. It is disappointing that $725 million of the $915 million of unappropriated expenditure resulted from the improper management of expense transfers between years and other administrative errors. Government departments need to improve how they manage their expenditure within the authority provided by Parliament.

3.6

In this Part, we discuss:

- why the Controller work is important;

- how much public expenditure was unappropriated in 2019/20;

- whether Covid-19 affected the level of unappropriated expenditure;

- how 2019/20 compared with previous years; and

- the need for better management of expenditure requiring appropriation.

Why the Controller work is important

3.7

Appropriations ensure that Parliament, on behalf of the public, has adequate control over how the Government plans to spend public money. It also ensures that the Government can be held to account for how it has used that money.

3.8

Most of the Crown's funding is obtained through taxes. The public should expect assurance that the Government is spending public money as intended by Parliament.

3.9

As the Controller, the Auditor-General helps maintain the transparency and legitimacy of the public finance system. The Auditor-General provides an important check on the system on behalf of Parliament and the public by providing independent assurance that the Government's spending is within authority. The Auditor-General also provides assurance that any government spending without authority has been identified and dealt with appropriately. As an Officer of Parliament, the Auditor-General is independent of the Government.

3.10

In the Appendix, we explain how public expenditure is authorised, who is responsible for managing it, and the Controller's role in checking it.

How much public expenditure was unappropriated in 2019/20?

3.11

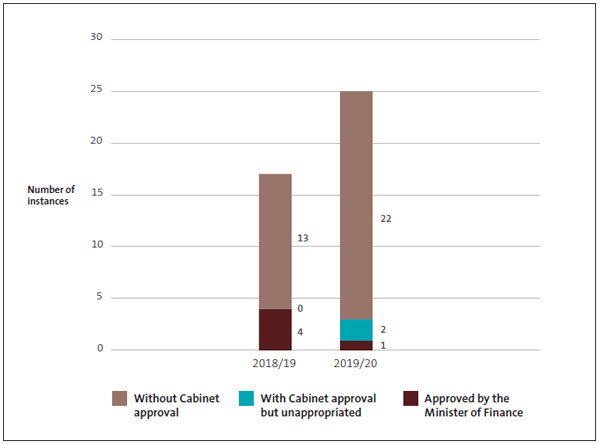

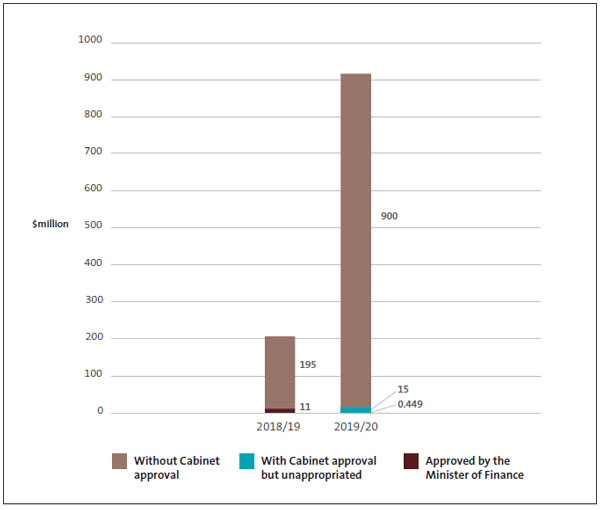

The Government's financial statements report 25 instances of unappropriated expenditure (2018/19: 17). Expenditure incurred above or beyond appropriation in 2019/20 was $915 million (2018/19: $206 million). Figure 4 shows a breakdown of unappropriated expenditure categories.4

Figure 4

Unappropriated expenditure incurred during the year ended 30 June 2020

| Category | Unappropriated expenditure by category | 2019/20 Number | 2019/20 $million* | 2019/20 Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act 1989. | 1 | 0 | Attorney-General |

| B | With Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but in excess of appropriation prior to the end of the financial year. | 2 | 15 | Conservation; Revenue |

| C | With Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but without appropriation prior to the end of the financial year. | 0 | 0 | Not applicable |

| D | In excess of appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 13 | 701 | Arts, Culture and Heritage; Building and Construction; Customs; Conservation; Defence Force; Environment; Justice; Prime Minister and Cabinet; Revenue |

| E | Outside scope of an appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 2 | 1 | Arts, Culture and Heritage; Environment |

| F | Without appropriation and without prior Cabinet authority to use imprest supply. | 7 | 198 | Business, Science and Innovation; Corrections; Defence; Foreign Affairs; Housing and Urban Development; Prime Minister and Cabinet; Tertiary Education |

| Total | 25 | 915 |

* Amounts are rounded to the nearest million. The amount in Category A was $449,000.

3.12

Unappropriated expenditure shown in Figure 4 was in three broad categories:

- Approved by the Minister of Finance (Category A): Small overruns of expenditure in the last three months of the financial year, which were within $10,000 or 2% of the appropriation, and were approved by the Minister of Finance under section 26B of the Public Finance Act.

- With Cabinet approval (Categories B and C): Expenditure incurred above or beyond the appropriation limits, with Cabinet authority to use imprest supply but not authorised by Parliament in an Appropriation Act before the end of the financial year.

- Without prior Cabinet approval (Categories D, E, and F): Expenditure incurred above or beyond the appropriation limits without any authority at the time it was incurred.

3.13

Figure 5 shows the number of instances of unappropriated expenditure for 2019/20 compared with 2018/19.

Figure 5

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure for the year ended 30 June 2020

Some unappropriated expenditure is lawful (Category A)

3.14

Section 26B of the Public Finance Act provides some flexibility for small expenditure overruns in the last three months of the financial year when it is generally too late to have additional expenditure (incurred under imprest supply) in the Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Act. It allows the Minister of Finance to approve excess spending of up to the greater of $10,000 or 2% of the appropriation if it is incurred between April and June (inclusive).

3.15

Although unappropriated, authorisation under section 26B makes this expenditure lawful. It then remains to be "confirmed" (rather than "validated") in the next Appropriation (Confirmation and Validation) Act. There are usually no more than a few items approved by the Minister of Finance each year.

3.16

During 2019/20, the Minister of Finance authorised one instance of unappropriated expenditure of $449,000 (2018/19: four instances amounting to $11 million). The Crown Law Office received approval to exceed its appropriation (under Vote Attorney-General) for legal advice. Activity increased more than anticipated due to the need to support the Government's response to Covid-19. Expenses exceeded the $23 million limit by $449,000.

Unappropriated expenditure incurred without Parliament's authority (Categories B-F)

3.17

Of the 25 instances of unappropriated expenditure in 2019/20, 24 were unlawful because the expenditure had not been authorised by an Act of Parliament (2018/19: 13 instances). This expenditure remains unappropriated and unlawful until it is validated by Parliament in an Appropriation Act, which is ordinarily enacted during May.5

3.18

The second Imprest Supply Act for the year provides interim authority for expenditure additional to that authorised in the Budget, within a specified spending limit. Expenditure under imprest supply must receive Cabinet approval before it is incurred. Because the authority is temporary, this expenditure must also be included in the Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Bill for the year in order to be appropriated before the end of the year, when the Bill is enacted. However, if such expenditure is not included in the Bill, then it is unappropriated and remains so until Parliament validates it.

3.19

In two of the 24 instances, government departments sought and received Cabinet's approval to increase their appropriations through the Supplementary Estimates6 and to incur expenditure under imprest supply in the meantime (see Figure 5). Although they received Cabinet approval for the expenditure, the government departments did not submit the figures for the Supplementary Estimates Bill and so Parliament was unable to authorise the expenditure before the end of the financial year.

3.20

Most instances of unappropriated expenditure are incurred without any prior authority. In rare instances, these result from unseen events (for example, costs of immediate responses to natural disasters or other emergencies). But in most instances, these can be avoided with better planning and management.

3.21

The remaining 22 instances of unappropriated expenditure are those in which government departments incurred expenditure that was unauthorised by Parliament and not approved by Cabinet under the requirements for using imprest supply. This is a significant increase on non-Cabinet approved expenditure from the previous year (2018/19: 13 instances).

3.22

Although the number of occurrences of unappropriated expenditure increased by nearly 50% in 2019/20, the value of unappropriated expenditure more than quadrupled. In 2018/19, the value of unappropriated expenditure was $206 million. In 2019/20, it was $915 million.

3.23

Figure 6 compares the dollar amounts of unappropriated expenditure for 2018/19 and 2019/20. The amount of unappropriated expenditure incurred without prior Cabinet approval to use imprest supply increased from $195 million in 2018/19 to $900 million in 2019/20.

Figure 6

Amount of unappropriated expenditure incurred without prior Cabinet approval for the year ended 30 June 2020

Why was the expenditure unappropriated?

3.24

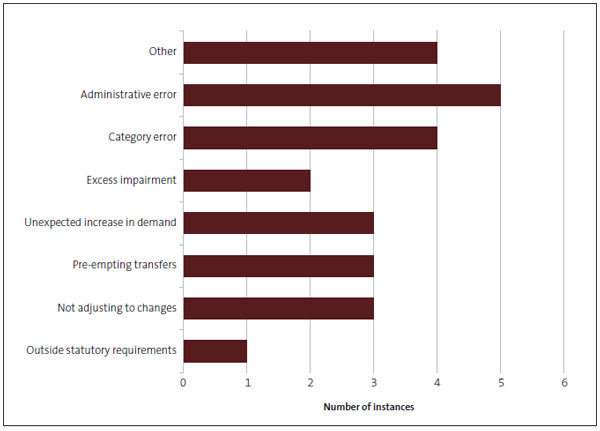

From the explanations provided in the 2019/20 Government's financial statements, we have put the 25 instances into eight categories that describe why the unappropriated expenditure came about:

- Expenditure was outside statutory requirements.

- Not adjusting to changes (that is, the government department did not seek to increase its spending authority to adjust to changes in its operating environment).

- Pre-empting transfers (that is, the government department incurred expenditure based on "in principle" funding transfers from the previous year before the transfers were confirmed and authorised).

- An unexpected increase in demand for services.

- Excess impairment expense for some assets (for example, loan write-downs).

- Category error (that is, applying an incorrect appropriation category to the expenditure).

- Administrative error.

- Other.

Figure 7

Reasons for unappropriated expenditure in 2019/20, by number of instances

3.25

Figure 7 shows that the most common reason for unappropriated expenditure was because of administrative errors. The second most common reason was because the government department did not have the type of appropriation required to authorise the type of expenditure incurred (category error).

3.26

Outside statutory requirements: The Ministry for the Environment incurred expenditure outside statutory requirements. The Ministry pays territorial local authorities 50% of the value of the Waste Disposal Levy collected by the authorities to fund their waste management and minimisation plans. To be eligible for this funding from the Ministry, the territorial local authorities must review their plans according to statutory requirements (including time frames). The Ministry made payments to some territorial authorities that had not met some of the statutory requirements. Therefore, these payments, which amounted to $1.3 million, were unauthorised and unlawful.

3.27

Not adjusting to changes: In three cases, government departments did not ensure that their spending authority kept pace with increases in costs. The Department of Conservation had insufficient appropriation to cover increased rates costs for the year. The New Zealand Defence Force exceeded two appropriations: Veterans Support Entitlement costs were higher than forecast as were Assessment, Treatments, and Rehabilitation costs due to a change in accounting standards.

3.28

Pre-empting transfers: We have previously urged government departments to better manage the transfer of funding authority between years. In 2019/20, three government departments7 received "in principle expense transfers" from 2018/19 but incurred $9.8 million of expenditure in anticipation of those transfers before they had been approved.

3.29

Unexpected increase in demand: Crown Law (see paragraph 3.46), the Ministry for the Environment, and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC) (see paragraph 3.47) all experienced an unexpected increase in demand for services, which led to unappropriated expenditure.

3.30

Excess impairment: Impairment to the book value of the National War Memorial resulted in an expense that exceeded the Ministry for Culture and Heritage's appropriation for the depreciation of Crown-owned assets. An actuarial valuation of legal aid debt resulted in an impairment expense that exceeded the Ministry of Justice's appropriation for it.

3.31

Category error: Four government departments incurred unappropriated expenditure because they did not have the right type of appropriation to authorise the expenditure. The government departments were the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (see paragraph 3.40), Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (see paragraph 3.49), Ministry for Culture and Heritage (see paragraph 3.50), and Ministry of Defence (see paragraph 3.52).

3.32

Administrative error: Three government departments were responsible for five instances of unappropriated expenditure as a result of administrative error when seeking additional authority from Cabinet and, subsequently, Parliament. The government departments included Inland Revenue (see paragraphs 3.35 and 3.39) and DPMC (see paragraph 3.38). Most of the unappropriated expenditure for 2019/20 ($715.7 million) came about through such errors.

3.33

Other reasons for unappropriated expenditure include:

- an unavoidable $151.8 million expense to the Crown resulting from a constructive obligation to decommission the Tui Oil Field (see paragraph 3.36);

- excess maintenance costs for the seismic strengthening of the National War Memorial's Carillon Tower ($6.7 million under Vote Arts, Culture and Heritage);

- the cost of facilitating asset transfers as part of a Treaty of Waitangi settlement, which exceeded appropriation by $2 million under Vote Conservation; and

- work needed under the Management of Historic Heritage appropriation (also through Vote Conservation) resulted in excess expenditure of $344,000.

Five instances account for almost all unappropriated expenditure

Two instances account for 90% of the unappropriated expenditure

3.34

Two instances make up 90% of the unappropriated expenditure:

- Inland Revenue's impairment of debt and debt write-offs ($676.8 million); and

- the costs to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment of decommissioning the Tui Oil Field ($151.8 million).

3.35

As a result of Covid-19's effect on the economy, Inland Revenue increased the amount of taxpayer debt written off and further impaired the value of taxpayer debt. It sought and gained Cabinet's approval to increase the relevant appropriation to cover the expense but, in an administrative oversight, did not seek Cabinet's express approval to use imprest supply in the meantime. Impairments and write-offs totalling $1,356.8 million were therefore incurred against an authority of $680 million, resulting in $676.8 million in unappropriated expenditure.

3.36

In late December 2019, Tamarind Taranaki Limited was placed in liquidation. This company was the operator of the Tui Oil Field, off the coast of Taranaki. It is usual for the operator to carry the liability to decommission an oil field in a way that ensures no harm to the marine and coastal environment. However, with the company liquidated, a constructive obligation for decommissioning the oil field fell to the Crown. The obligation created an immediate expense to the Crown, which, because this was an unanticipated event, was not authorised in advance through an appropriation. Although Cabinet approved a new appropriation in February 2020 under Vote Business, Science and Innovation for oil field decommissioning, the estimated decommissioning cost of $151.8 million had been incurred in December 2019 without appropriation.

Other items of unappropriated expenditure

3.37

Three instances make up 5% of the unappropriated expenditure:

- The Government's "Unite Against Covid-19" media campaign ($18 million).

- Inland Revenue's write-down of the value of student loans ($15.1 million).

- Expenditure for deferred payments for land sales administered by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development ($14.8 million).

3.38

In response to Covid-19, DPMC established an all-of-government response co-ordination team. This team was responsible for leading the "Unite Against Covid-19" publicity campaign. Cabinet had approved the expenditure, but an administrative oversight meant that DPMC did not have an appropriation that would authorise the expenditure. As a result, the $18 million spent on the campaign in 2019/20 was unappropriated.

3.39

When the Crown provides loans, they must be recorded in the financial statements at their "fair value". This often means that the initial carrying amount of the loan asset needs to be written down to its fair value, with the amount of write-down constituting an impairment expense. For Covid-19, Inland Revenue knew that it would need to increase the write-downs for student loans. It secured Cabinet's approval to increase the appropriation that authorises the impairment expense. Although the increase in expenses was initially authorised under imprest supply, it was not included in the Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Bill and therefore was not appropriated by Parliament before the end of the financial year. This resulted in an unappropriated expense of $15.1 million.

3.40

When the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) sold land on behalf of the Crown to developers under the Land for Housing Programme, it offered them deferred settlement terms of up to 360 days from the date of the title transfer. HUD considered it had an operating expenditure appropriation to authorise this activity. The developers are a type of trade debtor to the Crown, and the Ministry considered it was extending a form of trade credit to the purchasers. Under the Public Finance Act, trade credit can be extended for up to 90 days, but a deferred settlement for a longer period constitutes a loan. This loan requires the Minister of Finance's approval, and the expenditure must be authorised under a capital expenditure appropriation. Although HUD had the necessary approval from the Minister of Finance, its Vote had appropriations only for operating expenditure. Because the Vote did not include a capital expenditure appropriation for the lending, it resulted in $14.8 million of capital expenditure being unappropriated in 2019/20.

3.41

The amount of unappropriated expenditure in 2019/20 ($915 million) is historically high (see paragraph 3.54 and Figure 9). However, about 95% of the unappropriated expenditure (in the five cases mentioned above) resulted from:

- the cost to the Crown of an unavoidable constructive obligation;

- a misunderstanding about the appropriation category required; and

- administrative errors (that is, errors in the paperwork supporting the approval of the expenditure).

3.42

In some of those cases more careful management was needed.

Did Covid-19 affect the level of unappropriated expenditure?

The Government's Covid-19 response

3.43

We have been monitoring the expenditure authorised and incurred as part of the Government's response to Covid-19. During 2020, we published regular Controller updates (and other reports related to Covid-19) on our website. We consider it necessary to focus on Covid-related expenditure, given the substantial funding available for responding to Covid-19, the long-term implications for government debt, the speed of the Government's emergency response, and the extraordinary conditions under which the public sector has operated, particularly in the early stages of the Covid-19 lockdown.

3.44

Based on data received from the Treasury earlier in 2020, we determined that Cabinet approved about $26 billion for new appropriations created exclusively for the Covid-19 response and, of that, an estimated $15 billion was incurred by 30 June 2020. About $3.3 billion was authorised to top up existing appropriations to help with the Covid-19 response.

3.45

In our view, little of the unappropriated expenditure in 2019/20 was related to the Government's Covid-19 response. According to our analysis, five of the 25 instances of unappropriated expenditure related to the Covid-19 response, constituting $24.5 million of the $915 million unappropriated.

3.46

The increased demand for legal advice in response to Covid-19 in the last quarter of the financial year led to Crown Law exceeding its Legal Advice and Representation appropriation by $449,000. The Minister of Finance authorised this unappropriated expenditure under section 26B of the Public Finance Act.

3.47

In another instance of increased demand, the Government established a $25 million appropriation for 2019/20 to support local authorities and Civil Defence Emergency Management groups for costs they incurred in providing urgent community support. Support payments exceeded the appropriation in Vote Prime Minister and Cabinet by $3.8 million.

3.48

In two instances, expenditure on the Covid-19 response was applied as intended but the appropriations that were presumed to provide authority for the expenditure were the wrong category of appropriation.

3.49

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT) has for many years provided financial assistance by advancing money to New Zealanders in distress overseas. The terms of the advances have required them to be repaid promptly, usually within 30 days. This activity increased considerably in 2019/20 to help New Zealanders stuck overseas because of Covid-19. The advances were charged against MFAT's "Consular Services" expense appropriation but, because of the repayment terms, they constituted short-term loans, which instead required a capital expenditure authority. There was no non-departmental capital expenditure appropriation in Vote Foreign Affairs to cover the loans and, therefore, the expenditure of nearly $2.2 million was unappropriated. After realising the problem, MFAT immediately arranged for Cabinet to establish the required appropriation and an additional appropriation for expenses, such as foregone interest and any loan write-offs.

3.50

During 2019/20, in response to the economic effects of Covid-19, the Government decided to pay local media businesses in advance to run advertisements in 2020/21. However, because the advanced payments were interest free, they needed to be accounted for as concessionary loans. As a result, the carrying value of the loans had to be written down to reflect their fair value. The Ministry for Culture and Heritage charged the expense ($121,000) against the Grants and Subsidies appropriation, the scope of which does not authorise this type of expense.

3.51

The fifth, and largest, instance of unappropriated expenditure because of Covid-19 was the $18 million of expenditure for the "Unite Against Covid-19" publicity campaign. This was unappropriated because of an administrative error.

Consequences of Covid-19

3.52

As well as the five instances where the response to Covid-19 resulted in unappropriated expenditure, we have identified three instances related indirectly to the effect of Covid-19 on the economy and society:

- During the lockdown, the Ministry of Defence had to compensate a construction contracting firm that was unable to work. The normal construction costs were, as expected, authorised under a capital expenditure appropriation. However, the compensation costs ($1.4 million) could not be capitalised, and the Ministry had no operating expense appropriation to cover this sort of abnormal expenditure caused by the response to Covid-19.

- The other two instances relate to the economic effect of Covid-19 on the value of the Crown debtors. Inland Revenue needed to reduce the book value of debt owed to the Crown (that is, increase the expense of impairing the book value) for tax debt and student loans. Administrative oversights resulted in $692 million of unappropriated expenditure (see paragraphs 3.35 and 3.39).

How does 2019/20 compare with previous years?

3.53

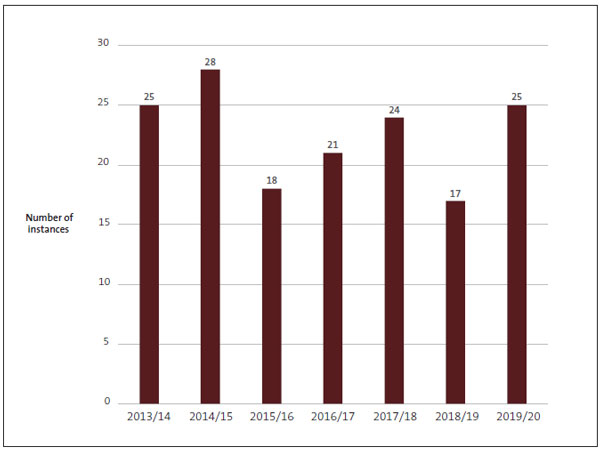

Figure 8 shows that the frequency of instances of unappropriated expenditure had fluctuated during the last seven years. Since 2014/15, when there was a peak of 28 cases of unappropriated expenditure, there have been notably fewer instances until the 25 cases in 2019/20.

Figure 8

Number of instances of unappropriated expenditure, from 2013/14 to 2019/20

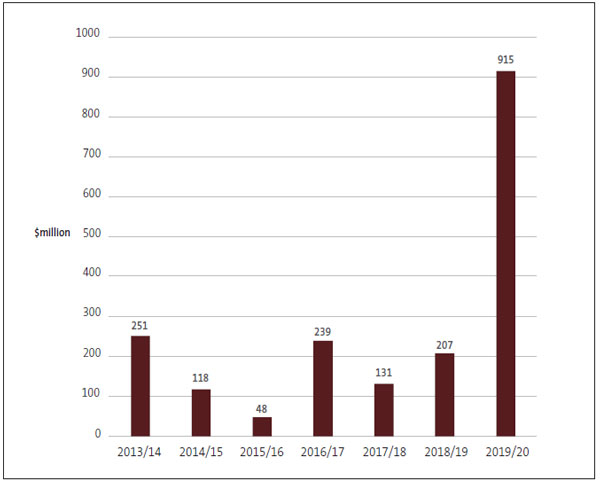

3.54

Figure 9 shows the dollar amount of unappropriated expenditure incurred during the last seven years.

Figure 9

Amount of unappropriated expenditure, from 2013/14 to 2019/20

Better management is needed

3.55

When the Government wishes to incur expenditure not yet authorised in an Appropriation Act, it can use Parliamentary authority provided in an Imprest Supply Act. Whereas Appropriation Acts specify public expenditure by way of the limits attached to appropriations, Imprest Supply Acts do not include these limits.

3.56

Recently, the amount of public expenditure Parliament has authorised through Imprest Supply Acts has increased considerably. In 2018/19, the second Imprest Supply Act8 authorised up to $16.3 billion. In 2019/20, the second Imprest Supply Act authorised up to $17.3 billion, which was boosted by a further $52 billion through a third Imprest Supply Act in March 2020. This was mainly in response to Covid-19. For 2020/21, Parliament has authorised $56.5 billion under the second Imprest Supply Act.

3.57

Expenditure incurred under imprest supply is authorised by Parliament after the fact, in the Appropriation (Supplementary Estimates) Bill, which is normally passed each June. The expenditure is reported to Parliament as a fait accompli and receives only limited attention. As such, with imprest supply Parliament has given the Government considerable scope to incur large sums of expenditure without prior scrutiny or specification.

3.58

In return for this freedom, we expect government departments to manage their expenditure in strict accordance with Cabinet's rules. It is therefore disappointing that $725 million of the $915 million of unappropriated expenditure resulted from not adhering to the requirements for managing expenditure under imprest supply.

2: Section 22 of the Constitution Act 1986.

3: Appropriations are authorities from Parliament that specify what the Crown may incur expenditure on (specific areas of expenditure). Most appropriations specify limits in terms of the type of expenditure (the nature of the spending), scope (what the money can be used for), dollar amount (the maximum that can be spent), and period (the time frame for which the authority is given).

4: New Zealand Government (2020), Financial Statements of the Government of New Zealand for the year ended 30 June 2020, pages 148 to 156.

5: The Confirmation and Validation Bill to verify the unappropriated expenditure from 2019/20 is expected to be passed in May 2021.

6: The Appropriation (2019/20 Supplementary Estimates) Act was enacted in June 2020.

7: The three departments were the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment; the Department of Corrections; and the New Zealand Customs Service.

8: We have not referred to the first Imprest Supply Acts for each year because those Acts are primarily to enable the Government to incur expenditure in lieu of Budget legislation being enacted.