Part 6: The Pacific Division

6.1

Many of the public concerns and allegations that prompted our inquiry related to Immigration New Zealand’s Pacific Division. These concerns were broadly about the integrity and probity of staff and compliance with systems, policy, procedures, and the law. Many particular incidents of concern involved senior staff, including the visa and permit applications for relatives of Mary Anne Thompson, which we discuss in Part 7.

6.2

Earlier Parts of this report described matters that apply to several, if not all, of the Immigration New Zealand branches that we visited. The matters discussed in this Part are specific to the Pacific Division.

6.3

When we started our inquiry, the chief executive of the Department had commissioned an external review of the Pacific Division.1 The chief executive is now responding to the recommendations of the review and the Minister of Immigration’s direction that he consider reintegrating all activities of the Pacific Division back into the core of Immigration New Zealand.

6.4

In this Part, we describe some important background material – the wider context of immigration in the Pacific, and how and why the Pacific Division was established – before discussing;

- leadership and management within the Pacific Division;

- visa and permit decisions made within the Pacific Division;

- implementation of the residual places policies; and

- our overall conclusions.

Immigration and the Pacific region

6.5

New Zealand is a member state of the Pacific region.2 Pacific Island countries are among our closest neighbours and New Zealand has long-standing historical, constitutional, political, social, and economic connections within the Pacific. For example, citizens of Niue, Tokelau, and the Cook Islands have New Zealand citizenship and there has been a special Treaty of Friendship with the Independent State of Samoa since 1962.

6.6

New Zealand’s interests in the Pacific are in regional leadership and stability, economic development, and security. New Zealand provided about $180 million in development assistance to the region in 2007/08.

6.7

Immigration policy is an integral part of New Zealand’s wider economic, security, and development policy in the Pacific.

6.8

There are usually large numbers of Pacific Islands people wanting to visit New Zealand for various reasons. The reasons include, for example, established historical, family, and community links with people living here, the generally low level of economic development and prospects in many Pacific countries, and the availability of social assistance (education and health in particular) in New Zealand.

Immigration New Zealand’s work in the Pacific

6.9

Most of Immigration New Zealand’s work in the Pacific region is in making visa and permit decisions. Policy advice and relationship management with Pacific governments and communities (onshore and offshore) are also aspects of its work.

6.10

In 2007/08, Immigration New Zealand issued 43,753 temporary permits for people from the Pacific, including permits issued under the Recognised Seasonal Employer Scheme (which we did not include as part of our inquiry).3

6.11

There are two main schemes for granting residence to applicants from the Pacific:

- Under the Samoan quota scheme, each year there are 1100 places for Samoan citizens.4

- Under the Pacific Access Category quota scheme, each year there are 250 places for citizens of Tonga, 75 for citizens of Kiribati, and 75 for citizens of Tuvalu.

6.12

These schemes recognise New Zealand’s special relationship with these countries. A residual places policy is in place to offer any unfilled places under each of these schemes to Pacific people already legally in New Zealand.

6.13

There are challenges – some of which exist in other offshore branches – in the operating environment for Immigration New Zealand’s branches in the Pacific. For example:

- Visas are commonly processed face to face because the local infrastructure is poor and there are cultural preferences for operating this way.

- The visa applications are often difficult to assess because the policy requires an assessment of the applicant’s standard of health in environments where the population health profile is generally poor, and because it can be difficult to confirm a person’s identity and background.

- There can be significant pressure on staff because of family and cultural obligations, particularly where the New Zealand public sector standards may contrast significantly with local norms.

- We understand that the public profile of Immigration New Zealand’s operations in Apia and Nuku’alofa is higher than in other offshore locations.

How and why the Pacific Division was established

6.14

The Pacific Division started operating in January 2005. Particular external pressures and concerns that led to setting up the Pacific Division were:

- a failure to fill quotas;

- an insufficient priority and focus on Pacific immigration matters; and

- uncertainty about whether offshore Pacific branches were adequately resourced and structured to address the challenges of operating in the Pacific.

6.15

Various Cabinet decisions at the time addressed some of these concerns, such as:

- setting up the residual places policies in November 2004 (described later in this Part);

- providing more settlement information to Pacific migrants;

- a communications campaign in New Zealand and in Pacific countries to improve relationships; and

- steps to better match Pacific migrants with potential employers.

6.16

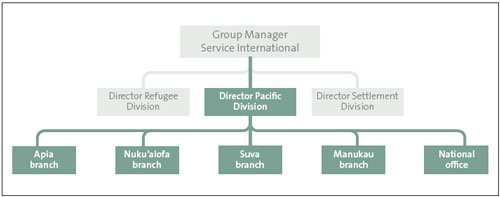

The Pacific Division formally became a part of the newly established Service International5 group in June 2005. The organisational structure of the Pacific Division is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17

Organisational structure of the Pacific Division

6.17

The purpose of the Pacific Division was to “specialise and lead our work with the Pacific, which will include our offshore offices in Apia, Nuku’alofa and Suva”.6

6.18

We were told during our interviews that the main areas of focus for the newly established Pacific Division were:

- filling the Samoan quota and Pacific Access Category quota;

- implementing the residual places policies; and

- improving relationships with other nations in the Pacific region by taking a different approach to interacting with them.

Leadership and management within the Pacific Division

In our view, the leadership and management practices within the Pacific Division contributed to our findings about visa and permit decision-making and the implementation of the residual places policies.

Lack of clarity about the role and the direction of the Pacific Division

6.19

We were given copies of presentations and speeches to help explain the vision and work of the Pacific Division. These emphasised the reason for creating the Pacific Division, the need for it to get under way quickly, and the value it would add. The Group Manager, Service International, told us that there were many attempts to explain the “value proposition” of the Pacific Division to staff in the Department. Despite these attempts, some staff (wrongly) thought that the new focus was because of the then Deputy Secretary (Workforce)’s empathy for the Pacific, rather than because the Pacific region was a strategic priority.

6.20

It was clear to us that the role and the strategic direction of the Pacific Division were never clearly understood by all staff, particularly those outside the Pacific Division.7

6.21

Crucially, this lack of clarity led to a low level of understanding and even misunderstanding of the role, mandate, and objectives of the Pacific Division. The lack of clarity contributed to some of the specific management and immigration decision-making issues we discuss in this Part. These include the isolation of the Pacific Division, the lack of co-operation between the Pacific Division and other parts of Immigration New Zealand and the wider Department, and a “facilitation” approach taken to approving visa and permit applications.

Inadequate operational planning for establishing the Division

6.22

The speed with which the Pacific Division was set up was mentioned often in our interviews with current and former staff. The Group Manager, Service International, told us that he was asked to bring forward the establishment date by seven months because of concerns raised in 2004 about immigration issues, such as not meeting immigration quotas.

6.23

The Pacific Division started operating without any establishment or implementation plans. The former Director of the Pacific Division told us that the immediate focus of the Pacific Division was on filling quota places and meeting targets under extreme urgency, and the necessary early planning work was never done. The Group Manager, Service International, told us that an internal review carried out in mid-2005 (see Figure 19) considered the nature and scope of the Pacific Division’s activities against what was already in place, and the changes required to meet deliverables. He considered that this was, effectively, the first establishment plan.

6.24

In our view, there was inadequate operational planning to ensure that the Pacific Division had sufficient resources and capabilities to carry out its functions effectively before it started operating. The shambolic way in which the residual places policies were implemented in 2004/05 also clearly illustrates the lack of planning – see paragraphs 6.61-6.99.

Once established, the Pacific Division often operated in isolation

6.25

Another view often expressed during our interviews was that the Pacific Division, during its early years, operated in isolation from the rest of Immigration New Zealand.

6.26

There was a lack of information-sharing and co-operation between the Pacific Division and the other parts of Immigration New Zealand. Tensions in the working relationships between the groups were clearly evident. The Group Manager, Service International, told us that the Pacific Division needed to carry out aspects of its work in a different way from the other parts of Immigration New Zealand to achieve its objectives.

6.27

An internal audit report in 2007 of the Pacific Division’s Manukau branch found that the Pacific Division had put considerable effort into designing systems and processes that were already being used in other parts of Immigration New Zealand. The Pacific Division operated some of these systems without the support of the Service Delivery and Service Design groups.

6.28

We were often told that a lack of immigration experience among key managers in the Service International group and Pacific Division was the reason for many of the Pacific Division’s operational problems. In our view, however, the more critical concern was the way in which the Division operated in isolation from the rest of Immigration New Zealand, without adequate co-operation, co-ordination, support, and resources.

6.29

We note that from early 2008, steps started to be taken to integrate the Pacific Division with the rest of Immigration New Zealand.

Poor managerial practices

6.30

We noted examples of poor managerial practices in the Service International group and its Pacific Division. These practices were identified in external and internal reports and reviews. Some of them suggested an “ends justifies the means” approach that meant poor adherence to proper public sector processes. The practices included poor budgetary practices and a lack of financial accountability, examples of questionable discretionary expenditure, and poor procurement and contracting practices. We discuss one example in detail because we considered it particularly concerning.

Contracting and recruiting to fill the position of Director of the Pacific Division

6.31

We looked at the Department’s contracting and recruiting practices to fill the position of Director of the Pacific Division. Concerns about this appointment have been raised publicly. The matter was the subject of an investigation in 2005, but we have found further problems. We do not comment on the suitability or performance of Mai Malaulau, the person who filled the position. Rather, our focus was on the actions of the Department in managing the contracting and recruiting arrangements.

6.32

The details of our findings are set out in Figure 18. Overall, Immigration New Zealand did not use a competitive process to fill the position of Director of the Pacific Division. Contracts, and later short-term employment agreements, were successively rolled over for more than 3 years, with no reviews of Ms Malaulau’s performance. Attempts to fill the position permanently were belated, few, and inadequate. There was a conflict of interest involved at the outset. Although the conflict was known about, it was not adequately managed until after an investigation was carried out. The Department’s answers to select committee and parliamentary questions about the contracting and employment arrangements were inaccurate and incomplete.

Figure 18

Our findings on the contracting and recruiting practices to fill the position of Director of the Pacific Division

| Initial contracting for the position Ms Malaulau was appointed as the Pacific Division’s Establishment Director in January 2005. Initially, she was appointed as an independent contractor, for a period of three months. She was paid a daily rate. Ms Thompson and Mr Tavita (Group Manager, Service International) had held a number of discussions about the need to appoint a Director of the Pacific Division. The position reported to Mr Tavita. During their discussions, Ms Malaulau’s name kept coming up as someone who had the right credentials and capabilities. Mr Tavita, at the request of Ms Thompson, was asked to provide a list of some suitable candidates for the position of Director of the Pacific Division. Ms Malaulau was included in this list. Mr Tavita contacted Ms Malaulau to see whether she might be interested in the role. Mr Tavita and Ms Thompson did not talk to any other potential candidates. The position was not advertised, and a competitive process for the contract, or formal proposals or applications, did not occur. Instead, Mr Tavita and Ms Thompson started discussions with Ms Malaulau based on their knowledge of people who might be suitable for the role. Ms Thompson made the appointment. Mr Tavita had a personal connection to Ms Malaulau. His wife and Ms Malaulau together owned and ran a consultancy business. Mr Tavita had previously been involved in that business. Concerns were raised by a staff member about the appointment soon afterwards. The Department commissioned an investigation by an external lawyer into that and other matters. The investigator reported in August 2005. He found that there were various discussions between the parties leading up to the signing of the contract. These discussions focused on details, including the rate Ms Malaulau would be paid. Most of the discussions appear to have taken place between Mr Tavita and Ms Malaulau, with Mr Tavita then reporting progress to Ms Thompson, who was the decision-maker. The investigator concluded that, overall, he had “not found anything improper or untoward”. He noted that the personal connection had never been hidden, but he indicated that it “would have been more prudent and appropriate had Mr Tavita played no, or a lesser role in the negotiations”. In our view, Mr Tavita had a conflict of interest and it was inappropriate for him to have been involved in the negotiations. There was a risk of an appearance of cronyism or favouritism in the appointment, and the informal and non-competitive selection process significantly increased that risk. Mr Tavita was excluded from later dealings about Ms Malaulau’s contract and Ms Thompson managed it. The investigation noted that Ms Malaulau’s initial contract had been extended for reasons that were sensible and appropriate. However, the extension had been handled informally and was not properly documented. The investigator noted that that was being addressed, and that in any case “steps are being taken to appoint a fulltime employee”. Subsequent issues with the contractual arrangements At that time, Ms Malaulau had been working for the Department for about seven months. The investigator had appropriately looked at the arrangements based on it being a short-term contract that was about to end. However, Ms Malaulau ended up staying in her role for more than 3½ years. There were several other problems with the way the Department handled the contractual arrangements. A further lengthy extension of the contract was not documented. Despite the adverse comment made in the investigation report about documentation, there were no records kept about extending the contract for the 15 months from September 2005 to December 2006. Ms Malaulau continued as an independent contractor for two years, which cost the Department about $400,000. Her daily rate would not have been out of the ordinary for a consultancy contract to deliver a very specific service, project, or outcome in a defined period of time, but that is not what she was doing. In effect, she was acting as a long-term fourth-tier manager within the Department. Recruiting for the position In December 2006, Ms Malaulau’s status was changed to an employee, under a fixed-term employment agreement. The substance of her role carried on largely as before. The term was extended a further three times, and she remained with the Department until September 2008. We were told that the series of short terms was because Ms Malaulau had made it clear that she did not want to work for the Department permanently. The Department made two attempts, in 2005 and 2006, to recruit for the position, without success. One of those attempts was an internal advertisement only. We understand that matters like this are sometimes overlooked for a while when there are more urgent operational issues to deal with. However, in our view, the Department did not try hard enough to fill the position permanently – especially during the two-year period when the position was being paid at consultancy rates. In 2007 and 2008 it seems that no recruitment efforts were made at all, even though the incumbent was continuing on a series of fixed-term arrangements (and even though the appointing letters indicated that attempts would be made to find a permanent employee for the role). There were no formal contract reviews at the end of each successive consultancy contract or fixed-term employment agreement. There were no formal performance reviews during Ms Malaulau’s time as an employee. We were told that the position was always intended to be permanent, and was focused on running the operations of the Pacific Division. Department’s answers to parliamentary and official information requests At times, the Department was not as open as it could have been in answers to select committee and parliamentary questions and official information requests about the arrangements. Answers in 2007 did not provide the full costs of the consultancy contract, and wrongly suggested that the contract had begun in May 2006. The Department’s answers to other questions indicated that the contract had come to an end because an employee had been appointed to the position. Those answers were correct but incomplete. They did not explain that the contractor had become that employee. |

Visa and permit decisions made within the Pacific Division

We found no evidence of widespread problems with integrity or probity in the Pacific Division. Staff were well aware of, and careful with, potential conflicts of interest. Visa and permit decision-making in the Pacific Division was of a significantly lower quality than it was in the rest of Immigration New Zealand. Concerns identified about the quality of decision-making were not acted on early or effectively enough.

Integrity and probity within the Pacific Division

6.33

As with our overall findings for Immigration New Zealand, we have not found any evidence of widespread problems with the integrity and conduct of staff in the Pacific Division. Operating in the Pacific does pose particular challenges and it is inevitable that integrity issues sometimes arise. This makes it important for the Department to have effective systems and processes in place to manage the risks.

6.34

Staff in the Pacific Division recognised that conflict of interest risks could be more acute because of pressure on staff from family, community, or cultural obligations.8 Staff were generally aware of the need to identify and manage conflicts of interest, both actual and perceived.

6.35

Staff in the Pacific branches we visited often took a broad interpretation of what constituted a conflict of interest. For example, if an applicant lived on their street or their neighbourhood, or had the same family name, they would declare it as a conflict of interest even if they did not know the person. In other situations, visa and permit applications would not be allocated to an Immigration Officer for processing if the applicant and Immigration Officer were of the same nationality. While these situations do not constitute conflicts of interest, we consider such an approach has been beneficial. It has reinforced the importance of managing conflicts of interest, and also protected staff who may feel pressure from their family or the community.

6.36

Some branches also took steps to manage potential conflicts of interest that could arise because of local customs and norms. For example, we were told that the Tongan branch office has signs advising applicants that gifts would not be accepted by Immigration Officers. This is a useful initiative that other branches could adopt.

6.37

We did find one area of concern. The former Director of the Pacific Division told us that the former Deputy Secretary (Workforce) received many direct and informal requests from people she knew (or who knew of her as the head of Immigration New Zealand) to help with their application or to answer enquiries. These informal enquiries were usually referred to the Director for action, who would pass it to the branch concerned. We were told that such direct approaches became known within the Pacific Division as “the express service”. We were also told that some staff were annoyed about receiving queries from people who used Ms Thompson’s name. Ms Thompson told us that she did not encourage these approaches. She told us that an email was sent to all staff telling them to be cautious about people using Ms Thompson’s name, and asking staff to follow the correct process.

6.38

It is important that senior managers recognise the risks that can arise from staff perceptions in such situations. Senior managers need to manage the risks carefully with clear communication and behaviour consistent with that communication.

“Facilitation” approach to handling visa and permit applications

6.39

A particular focus for the newly established Pacific Division was to fill quotas and improve relationships with external stakeholders, including Pacific governments and communities.

6.40

The former Deputy Secretary (Workforce), Ms Thompson, established a change in approach in Immigration New Zealand. Her expectation was that staff would be facilitative, transparent, and customer-focused in how they approached their work. This was commonly called “facilitation” within Immigration New Zealand.9 While this approach was adopted throughout Immigration New Zealand, it was particularly evident in the Pacific Division.

6.41

Ms Thompson told us that facilitation meant a customer-service approach that tried to help the public identify which particular policy had requirements they might meet, rather than simply telling them they did not meet the policy requirements. Facilitation was described to us as being helpful rather than obstructive. Ms Thompson also said that internal communications were clear that the facilitation approach was to be based on lawfulness and integrity – it was not about favouritism, and it was not about breaking the law.

6.42

It was clear from our interviews and reviews of files that the Pacific Division placed a great deal of emphasis on communicating and helping people to apply and meet immigration policy. It was seen as a tangible way in which the Department could demonstrate to Pacific governments and communities that it was addressing their concerns about immigration. Some examples of facilitative activity were:

- providing advice and settlement information to migrants under the Samoan quota scheme and the Pacific Access Category quota scheme;

- holding community meetings to give information to Pacific communities about the new residual places policies; and

- building relationships with employers to help people successful in the Samoan quota and Pacific Access Category quota ballot10 find jobs.

6.43

The facilitation approach helped to fill the quotas. However, the approach was sometimes interpreted by Immigration Officers too broadly. For example:

- An Immigration Officer who was presented with evidence that a job offer was fraudulent allowed the applicant to resubmit another job offer, without adequately considering what the initial fraudulent job offer indicated about the applicant’s character (another policy requirement).

- An application was being considered for a long time and the Pacific Division was “facilitative” on many aspects of the policy requirements – including the job offer, and acceptable standard of health and character. While the final decision was not technically outside policy, we did not see a similar approach being taken in other parts of Immigration New Zealand, meaning that Immigration New Zealand was inconsistent in its dealings with the public on immigration applications.

6.44

The 2006 post-establishment review of the Pacific Division found that there were risks, particularly in the Auckland branch, in the appropriate balance between facilitation and making visa and permit decisions. The review found that branch staff were “highly facilitative in their approach to filling the various Pacific quotas despite the fact that they are solely responsible for related decisions”. Separating the two functions was considered best practice and desirable, and we agree with these views.

6.45

Immigration New Zealand did not act to mitigate the risks identified by the post-establishment review. In our view, Immigration New Zealand did not recognise the full extent of the risks involved in the facilitation approach, and did not provide staff with adequate guidance and training about using the approach. As a result, the risks were not adequately managed.

Quality of visa and permit decisions made in the Pacific Division

6.46

There have been various reviews of the Pacific Division in its short life. The nature of these reviews is summarised in Figure 19.

Figure 19

Various reviews of the Pacific Division commissioned by the Department

| 2005 internal review An internal review was carried out in mid-2005, to determine the nature and scope of Immigration New Zealand’s presence and service in the Pacific. The review recommended two phases of changes. Phase one of the changes was implemented from January 2006, and centralised residence decisions for the Pacific region in the Manukau branch. The branch was made permanent and increased its staff numbers. Other changes included sending New Zealand staff to offshore branches to support branch managers, using a regional verification and liaison officer to enhance border security, and the enhancement of functions in offshore branches (such as community outreach and employer engagement). Phase two of the changes was never implemented because of funding constraints. 2006 post-establishment external review An external consultant carried out a post-establishment review of the Pacific Division in October 2006. The review looked at, among other aspects, the purpose of the Pacific Division, the funding for activities (existing and planned) and the processes for customer services and ensuring the quality and consistency of decision-making. Various areas for improvement were identified, including the need to more precisely define the role, responsibilities, and desired outcomes of the Pacific Division, and to balance the risk between facilitation and decision-making. 2008 external review An external review, commissioned in February 2008, occurred in two phases. The first phase established the terms of reference and was completed in July 2008. The second phase reviewed the operation and structure of the Pacific Division. The final report on the second phase was completed in December 2008. The review made several non-structural recommendations covering strategic and operational matters. It also recommended that the Department should, in the long term, consider the organisational structure that would best deliver Pacific immigration services, and presented options for structural change. |

6.47

There were some concerns being identified as early as January 2006 about aspects of the visa and permit decisions made in the Pacific Division. The 2005 internal review (completed in 2006) of the Pacific Division identified “concern about processing and decision-making carried out in overseas locations by locally engaged staff who may not have a strong and informed appreciation of New Zealand’s interests”. These concerns would have pre-dated the establishment of the Pacific Division because the overseas locations became part of the Pacific Division only in mid-2005. Changes were made after this review, as described in Figure 19.

6.48

The 2006 post-establishment external review commented on the verification practices in the Pacific Division. It found that:

- the requirement that applicants under the Samoan quota scheme, and Pacific Access Category quota scheme, and residual places policies, have a minimum level of earnings led to significant risks with fraudulent job offers; and

- the absence of sufficiently qualified verification officers (1.5 full-time equivalent staff in the Pacific Division’s Manukau branch, managing a workload of 160 files at that time) was cause for concern.

6.49

There were no additional verification officers in the Pacific Division’s Manukau branch when we carried out our fieldwork in late 2008.

6.50

The external review of the Pacific Division in 2008 found that the withdrawal of the Central Verification Unit’s services in 2005/06 (because it was not funded for Pacific Division activity) had a significant effect on workloads and quality.

6.51

In May 2007, a meeting of senior managers of the Pacific Division acknowledged that there had been a pattern of errors or omissions in practices, identified from complaints to the Deputy Secretary (Workforce), and that there was a need to improve systems, processes, tools, and skills in the Pacific Division.

6.52

In July 2007, the Residence Review Board11 provided Immigration New Zealand with an analysis of residence applications decided by the Pacific Division’s Manukau branch that had been appealed to the Board in the six-month period from 1 January to 30 June 2007. This report showed that 74% of the appealed decisions had been reversed or sent back to the Pacific Division for reconsideration because the assessment was incorrect. This compared unfavourably with the overall Immigration New Zealand figure (which included the Pacific Division) of 30%. Common errors included a failure to put potentially prejudicial information to applicants, or flaws in the way in which they were put, and inadequate reasons provided for the decision to decline residence.

6.53

The Residence Review Board report confirmed that urgent action was needed to remedy systemic errors. Immigration New Zealand’s response to the Residence Review Board analysis noted that one of the reasons for the errors was the challenging transition to having all residence decision-making moved onshore to the Manukau branch from 1 January 2006.

6.54

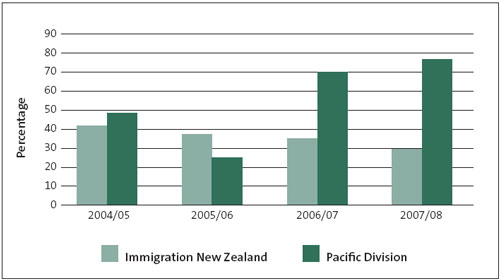

Figure 20 shows some statistics of the Residence Review Board decisions for Immigration New Zealand and the Pacific Division for the four years ending 2007/08. It shows that an extremely high proportion of Pacific Division decisions appealed to the Residence Review Board were incorrect in 2006/07 and 2007/08, compared to Immigration New Zealand as a whole.

Figure 20

Decisions reversed or sent back to Immigration New Zealand or the Pacific Division by the Residence Review Board, as a percentage of the residence decisions appealed to the Residence Review Board

6.55

An August 2007 internal audit report of the Pacific Division’s Manukau branch found “overall systems, procedures and controls at the branch were operating inconsistently” and the “documentation and disclosure of decision making was inadequate in many of the applications” reviewed. The review also raised concerns about verification, timeliness of decision-making, and poor workflow management.

6.56

The Deputy Secretary (Legal) also reviewed particular complaints in late 2007 and found serious systemic deficiencies such as inconsistent and low-quality decision-making, a lack of adequate supervision and quality control, and a lack of training.

6.57

A Pacific Quality Training programme was delivered in the Pacific Division branches between May and July 2008.12 The programme was aimed at addressing the skill and procedural shortcomings identified in how visa and permit decisions were made. Staff in the branches we visited told us that this training was long overdue and welcomed. Many staff expressed the view that they now understood what they had to do and felt better equipped to do their job.

Our review of visa and permit decisions

6.58

The overall results of our review of visa and permit decisions (across all the branches that we visited) are discussed in Part 5. The Pacific Division had a much higher proportion of decisions (compared to Service Delivery branches) that we categorised as questionable or poor, compared to the Service Delivery branches.13 We found:

- inadequate verification;

- a failure to put potentially prejudicial information to applicants;

- a lack of clarity about how core policy requirements, such as the eligibility or health of applicants, was assessed (in some cases, it was difficult to understand how these requirements were met given the information on files); and

- a greater than acceptable level of inconsistency between Immigration Officers in how applications were assessed and documented.

6.59

There were many early indicators of concern about how visa and permit decisions were made in the Pacific Division. We would have expected action much earlier to address the concerns.

6.60

We acknowledge that we reviewed decisions made in the two-year period ending 30 June 2008. Therefore, it was too early for us to assess what effect the Pacific Quality Training programme might have had.

Implementing the residual places policies

The residual places policies were poorly implemented. There was inadequate planning and resources for the implementation, which led to disorganised systems for processing applications. An oversight in the policy led to lengthy delays for some applicants in gaining residence. Guidance for staff on how section 35A processes related to the residual places policies was late and unclear, which meant that people were likely to have been given inconsistent information. Some decisions were made that seemed to contradict the intent of the residual places policies.

6.61

Implementing the residual places policies was a significant focus for the newly established Pacific Division. The residual places policies, however, were not prepared by the Pacific Division. The SSC noted in an investigation it completed into Immigration New Zealand in 2008 (discussed in Part 7) that it had difficulty establishing simple facts about how the residual places policies were administered, and that there was much confusion among staff about how the policies were intended to apply in practice.14 Some of the submissions we received from members of the public when we started our inquiry also raised concerns about the residual places policies. For these reasons, we decided to examine in detail how these policies were implemented.

Background

6.62

In 2004, the Government asked the Department to review the operation of the Samoan quota and Pacific Access Category quota schemes, after the quotas were not filled in previous years. The review resulted in the creation of the residual places policies, allowing some places to be filled from within New Zealand by citizens of the Independent State of Samoa or Pacific Access Category countries who were lawfully in New Zealand and had a job offer. The Residual Quota Places Policy for Samoan citizens and the Residual Pacific Access Category Places Policy for citizens from the Pacific Access Category countries came into effect on 15 November 2004 and became part of the official government policy for residence in New Zealand. The specific intent of the residual places policies was to make sure that the Samoan quota and Pacific Access Category quota were full.

6.63

Initially, there were 1297 residence places available for the Residual Quota Places Policy for Samoan citizens and 684 for Residual Pacific Access Category Places Policy for citizens from the Pacific Access Category countries.15 Applications had to be submitted between 1 December 2004 and 31 January 2005. The deadline for applications was later extended to 31 March 2005.

6.64

The Pacific Division promoted the residual places policies extensively to Pacific communities in New Zealand. The Pacific Division held several community meetings in major cities, particularly Auckland, and had regular advertising slots on Pacific radio networks. Senior managers, including Ms Thompson, attended some of these meetings.

6.65

The Palmerston North Service Delivery branch was responsible for processing the first 370 applications received. It stopped processing applications after 30 June 2005. The Pacific Division’s Manukau branch was responsible for processing the remaining applications when it was established in January 2005. We examined the systems in place for the applications processed by the Pacific Division’s Manukau branch, because this was the area in which concerns were raised.

6.66

The critical requirements of the residual places policies were that applicants were lawfully in New Zealand at the time of their application for residence, and had an acceptable offer of employment (or had a partner who had an acceptable offer of employment). The health (medical certificate) and character (police checks) requirements did not have to be submitted at the time of the application.

6.67

The residual places policies stated that “applications that are lodged in the prescribed manner (that meet all mandatory lodgement requirements) will be processed in the order in which they have been received”.

6.68

A ballot system is used for the Samoan quota and Pacific Access Category quota schemes. Registration is required, and if a registrant is successful in the ballot then they are invited to apply for residence. The ballot system is used to manage the fairness and equity for each registrant and also to enable the Department to manage the numbers of applications. We were told that a ballot system was not used for the residual places policies because of the longer timeframes involved in a ballot system.

Implications of the lack of a lapsing provision

6.69

The residual places policies did not have a lapsing or declining provision. In other words, applications could not be turned down because there were no places available. Both policies said:

If more applications are received than there are places to fill, the additional applications will be accepted and processed first if there are further places to fill.

6.70

There was considerable interest in Pacific communities about the residual places policies and the Department’s communication campaign was very successful. Because of this, the number of applicants greatly exceeded the initial number of places available under the Pacific Access Category residual places policy (see Figure 21).

Figure 21

Residual places policies: total applicants and applicants who met policy requirements, compared to places initially available

| Total applicants* | Number of residual places available (A) | Applicants who met residual places policy requirements (B) | (Shortfall of places available) / Places left over (A – B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific Access Category quota | 3471 | 684 | 2418 | (1734) |

| Samoan quota | 1320 | 1297 | 1034 | 263 |

| Total | 4791 | 1981 | 3452 | (1471) |

* For applications submitted between 1 December 2004 and 31 March 2005.

6.71

Because the places in the Pacific Access Category residual places policy were over-subscribed, the Government approved a further 1800 places under the Pacific Access Category residual places policy during the three-year period from 1 July 2005 to 30 June 2008.

6.72

We were told that the lack of a lapsing provision in each residual places policy was an oversight. That oversight was corrected in November 2005, well after the application closing date of 31 March 2005. It is unclear why the deadline for applications was extended for both policies from the original end date of 31 January 2005 to 31 March 2005.16 Before the extension, it was evident that demand for places was high.

6.73

Because of the lack of a lapsing provision, a large number of applicants have had to wait a number of years to gain residence, even though their applications met the policy requirements. In the meantime, they have had to apply to have their temporary permits renewed (sometimes more than once). Also, applications under residual places policies have not been opened since March 2005 because of the need to first deal with the backlog of applications.

6.74

This has been an unsatisfactory situation for the Department, applicants, and would-be applicants. We make no comment on the residual places policies but, in our view, this situation is a reminder of the need for policy to be carefully prepared, so there are no unintended consequences that can adversely affect people and public resources.

Some Cabinet decisions were not certified as Government policy for residence

6.75

The Act requires Government policy for residence (Government Residence Policy, or GRP) to be in writing and certified by the Minister of Immigration. Decisions made by Cabinet have to be certified before they become GRP.

6.76

After an internal review of Pacific residence policies in 2008, Immigration New Zealand found five instances where Cabinet decisions transferring or re-allocating residence places under the Samoan quota and Pacific Access Category quota and their respective residual places policies had not been certified as GRP.

6.77

This oversight affected two groups of people – those already granted residence permits outside the GRP, and those applicants whose applications had been put on hold until further residence places became available.

6.78

Action has been taken to ensure that the affected applicants are not disadvantaged by the departmental oversight.

6.79

We are pleased that Immigration New Zealand has made changes to its systems and processes to ensure that all Cabinet decisions involving changes to GRP receive the appropriate certification.

| Recommendation 17 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Department of Labour embed the changes it has made to the systems and processes for certification of amendments to Government Residence Policy, and regularly confirm that certifications are complete. |

Systems for processing residual places applications were inadequate

6.80

When responsibility for processing applications under the residual places policies was transferred to the Pacific Division in January 2005, the Pacific Division:

- did not have any implementation plans in place setting out how it would carry out its new responsibility;

- did not have adequate processes in place to deal with applications;

- had insufficient resources, both staff and physical; and

- had not received any particular training to ensure that staff knew what to do, and to ensure that the policies would be consistently interpreted.

6.81

Staff involved with processing these applications described the situation as chaotic.

6.82

Each policy required the applications to be processed “in the order in which they were received”. Staff told us that they tried to process applications in date order as best they could. However, they were not always able to do so:

- Applications were not always date-stamped when they were received. Some applications were sent to another Immigration New Zealand branch without being date-stamped, and were then forwarded in bulk to the Pacific Division. Staff had to look at parts of the application (such as the date of signing) to see if they could reasonably approximate the date of receipt.

- Applicants were not required to submit health and character documentation with their application, but were asked to do so at a later stage. It took longer to get these documents for some applicants, so staff had to put the processing of such applications on hold and move onto the next application. From a workflow management perspective, this was clearly necessary. However, there was confusion among staff about how the policy was to be interpreted – did “processed in the order in which they have been received” mean fully processing until the application was decided, or did it just mean lodging the application?

- Until the end of June 2005, the Palmerston North branch was processing applications at the same time as the Pacific Division. This added further complication to the processing, and in identifying when the residual places were filled.

6.83

Immigration New Zealand had an obligation to put basic processing controls in place to ensure that these applications were processed in keeping with government policy. It failed to do so.

6.84

We cannot give any assurance that residual places policy applications were processed in the order in which they were received. However, because of the lack of a lapsing provision in each policy, it is unlikely that applicants would have been improperly denied residence. At worst, they would have had to wait until further places became available before gaining residence. It is hard to be definite about the numbers of applicants who may have been affected in this manner because of the poor systems in place.

6.85

We note that the Department’s internal audit group did some work to provide assurance that the closing date for the residual places policies was implemented correctly. This audit identified the decisions involving Ms Thompson’s relatives, discussed in Part 7.

Section 35A decisions and the residual places policies

6.86

In Part 5, we described Immigration New Zealand’s ability to grant permits of any type under section 35A of the Act to restore lawful immigration status to individuals in certain circumstances.

6.87

The Pacific Division had widely promoted the residual places policies to Pacific communities in New Zealand. Staff told us that it was evident from an early stage that people unlawfully in New Zealand became interested in whether the residual places policies provided an opportunity to rectify their unlawful status. This increased the interest in the policies.

6.88

Immigration New Zealand had not anticipated the interest in the residual places policies from people unlawfully in New Zealand. There was no policy guidance in place before the residual places policies were introduced on how to deal with section 35A requests from people wanting to apply for a residual place.

6.89

We were told that senior managers presenting at the community meetings encouraged people unlawfully in New Zealand to come forward to rectify their status. Although the residual places policies were not meant to be an opportunity for those unlawfully in the country to change their status, it was clear that many people in the community perceived it this way.

6.90

On 1 March 2005, a guideline entitled Section 35A Customised Service Process was issued to the Immigration New Zealand senior management team, service managers, and the Pacific Division to provide some guidance. The guideline noted that the aim was to:

- encourage genuinely well-settled people who may be unlawfully in New Zealand to come forward (with an outcome of reducing the “deep seated overstayer situation”); and

- ensure that the integrity of section 35A requirements and procedures as set out in the internal administration circular was preserved.

6.91

The guideline went on to note that:

- The instruction was not to be misconstrued as providing a “defacto [sic] source of candidates” for the quotas. The facilitative approach was not to be seen as a way of bypassing the Government’s decision that only people lawfully in New Zealand were eligible for the quotas and the residual places policies.

- The Pacific Division would act as advisors to delegated officers by conveying insights on individual cases and linking with Pacific communities.

- Clients had to demonstrate genuine commitment to lodging a section 35A request – if they did they would be allowed a two-month grace period to prepare their section 35A submission.

6.92

A further memorandum was issued on 24 May 2005 to provide more guidance and to ensure consistency in the application of section 35A. It was issued to answer questions that had arisen since the 1 March guideline. This memorandum – intended to guide staff in making their decisions – stated that:

The applicant did not need to indicate they wanted to apply for residence nor should they otherwise expect to qualify for residence in deciding to grant a section 35A permit. The residence policy under which the applicant would be expected to apply did not have to be open.

6.93

The Office of the Ombudsmen received a number of complaints about how section 35A requests were considered by the Pacific Division when the residual places policies were involved. The Ombudsmen noted that a common theme in the complaints was a lack of understanding or certainty among complainants about the relationship between the section 35A processes and the residual places policies. Complainants had gained the impression that there were inconsistencies in Immigration New Zealand’s decision-making.

6.94

Based on our discussions with staff and review of the relevant guidance documentation, we can understand why people dealing with the Pacific Division formed this view. We expected guidance to have been prepared at an early stage to ensure that clear messages were given to staff and to the people making section 35A requests about how section 35A processes related to the residual places policies. Although guidance was developed later, it did not resolve the uncertainties.

6.95

During the period that the residual places policies were open, the Pacific Division received many requests for permits under section 35A. About 32217 temporary permits were granted under section 35A to allow 812 people to test their eligibility under the residual places policies. About 642 of the 812 people obtained residence. This represents about 19% of all the applicants who met policy requirements and obtained residence.

6.96

A staff member told us that priority was given to section 35A requests because of the deadline for the residual places policies. One staff member told us that they spent “three minutes” on each request during this peak time. We had concerns about some section 35A decisions we examined. Figure 22 summarises one particularly problematic example. The example highlights problems both in the section 35A temporary permit decision and the subsequent residence decision.

Figure 22

Example of a problematic section 35A and residual places policy decision

| A person had been in New Zealand unlawfully for about eight years. Two previous requests to the Associate Minister of Immigration to intervene and grant residence had been declined. A section 35A request was declined on 22 March 2005. A second section 35A request was accepted and the person was granted a temporary work permit on 29 March 2005. The notes in the AMS show that the decision-maker knew that previous Ministerial requests had been declined but decided that the applicant was well settled, had a genuine job offer, and was likely to qualify under the residual places policy. The person applied for residence under the applicable residual places policy on 30 March 2005. While the residence application was being considered the person was convicted on two counts of serious assault and one count of drink-driving. The person had also had two earlier convictions for drink-driving when not on a lawful permit. These convictions were not identified as part of the section 35A work permit decision, which requires the decision-maker to consider the applicant’s character. The decision-maker approved a character waiver to the residence application and granted a residence permit on 12 December 2006. The reasons given for the character waiver were the person’s clean police record in their home country, completion of reparation and community work hours and an anger management course, the job being on the skills shortage list, and the person being well settled. Letters of support were received from the family, employer, and community leaders. While the decision-maker had the delegation to approve the character waiver and make the decisions, we had significant concerns with both decisions because it was hard to understand how the decision could be reached given the information on the files. This case also illustrates how different judgements can be reached by different decision-makers. |

6.97

We were also told that there were tensions in Immigration New Zealand about what was seen as the Pacific Division’s facilitative approach to section 35A requests and how other branches approached the same requests. This added to the misunderstanding about the role and mandate of the Pacific Division and may have added to the Pacific Division’s isolation from the rest of Immigration New Zealand.

6.98

The policy guidance was clear that section 35A requests were not to be used to bypass the residual places policies’ requirement for applicants to be lawfully in New Zealand. However, the end result was that many people unlawfully in New Zealand were granted residence under the residual places policies by first restoring their lawful status through section 35A. This outcome seems to contradict the intent of the residual places policies.

6.99

We have no comment on the residual places policies, but we consider that inadequate thought was given to the practical matters that would arise when they were implemented, which would need policy guidance. The Pacific Division was not adequately prepared to deal with section 35A requests in a consistent and effective manner that met the intent of the residual places policies.

| Recommendation 18 |

|---|

| We recommend that the Department of Labour identify the lessons learned from the matters of concern that we have identified in the development, promulgation, and implementation of the residual places policies, consider what changes need to be made to systems, processes, and practices, and implement the necessary changes. |

Overall conclusions

6.100

We have found many leadership, management, and decision-making issues that have severely affected the operation of the Pacific Division since it was established in 2005. The lack of any proper planning for setting up the Pacific Division meant that staff in the Manukau branch in particular had to cope with the difficult and challenging task of implementing new residual places policies without adequate planning, resources, guidance, or support.

6.101

Many of these concerns were identified in internal audit reports or other reviews of the Pacific Division and were known to the management of the Department. It was clear that there was a level of concern about the Pacific Division’s performance among the wider Department and these concerns were brought to the attention of the former Deputy Secretary (Workforce) and the chief executive. However, we consider that the cumulative picture of concern that was building was not recognised and dealt with early enough. While there were some attempts by the Department to take action and ensure that the managers were held to account for changes needed, it was not sufficient or effective. We acknowledge that some action has been taken recently by the Department to remedy some of these issues, such as the lack of training.

6.102

It is important to note that the Pacific Division did achieve some of the outcomes it was seeking to achieve, in particular meeting targets for the Samoan quota and the Pacific Access Category quota schemes. The external review of the Pacific Division in 2008 also found that the Pacific Division had helped improve external stakeholder relationships, and played a significant role in developing and implementing the Recognised Seasonal Employer scheme.

6.103

The chief executive is considering the options for change in the Pacific Division now that the review he commissioned in 2008 is complete.

1: This external review was commissioned in February 2008 and occurred in two phases. The first phase established the terms of reference for the review of the Pacific Division and was completed in July 2008. The second phase reviewed the operation and structure of the Division to make an assessment of achievements, issues, and areas requiring attention. The final report on the second phase was completed in December 2008 and released publicly in March 2009.

2: The Pacific region includes 22 Pacific Island countries and territories.

3: The Recognised Seasonal Employer Scheme has operated since 2007, allowing the temporary entry of overseas workers to work in the horticulture and viticulture industries to meet labour shortages. The scheme is geared towards Pacific countries. Workers must apply for limited purpose work visas, meet health and character requirements, and show that they will leave New Zealand at the end of their stay.

4: The Samoan quota scheme was established in 1970 under the Treaty of Friendship.

5: We did not look at the Refugee and Settlement Divisions as part of our audit.

6: Consultation document produced by the Department of Labour (October 2004), Making Workforce Work – Proposing a Way Forward, Wellington.

7: Both the 2006 post-establishment review and the December 2008 review of the Pacific Division identified similar concerns (see Figure 19 following paragraph 6.46).

8: These issues are not uncommon, and are faced in varying degrees by staff in other regions and countries.

9: We were told that the notion of “facilitation” was first introduced to Immigration New Zealand in 2002, for dealing with applications for the skilled migrant scheme of the New Zealand Residence Programme.

10: See paragraph 6.68 for a description of how the ballot system operates.

11: The Residence Review Board is an independent judicial appeal body established under the Immigration Act 1987 that hears appeals by unsuccessful applicants for New Zealand residence visas or permits.

12: A small amount of training was provided in the Pacific Division from late 2007. It identified the need for further training, and led to the Pacific Quality Training initiative.

13: We examined both temporary entry and permanent residence decisions. Permit categories we examined included the residual places policies and decisions made under section 35A of the Immigration Act. We did not examine decisions made under the Recognised Seasonal Employer scheme.

14: State Services Commission (2008), Investigation of the Handling by the Department of Labour of Immigration Matters Involving Family Members of the Head of the New Zealand Immigration Service, State Services Commission, Wellington, Appendix J.

15: There was some uncertainty at the time about the numbers of places available under the residual places policies, because the numbers depended on the results of the 2004 ballot process for the Samoan quota scheme and Pacific Access Category quota scheme.

16: The time limit was not specified in Cabinet papers or Government residence policy. It was specified in Internal Administration Circulars, which have the status of an instruction to Immigration Officers. No Immigration Officer had the authority to accept applications received after the closing date.

17: We cannot be exact about the numbers because section 35A requests are not directly linked in the AMS system to the later residual places policy application. We have estimated the numbers by identifying how many requests for section 35A decisions were made within two months of a residual places policy application.