Part 5: Managing collection information

5.1

In this Part, we discuss how museums gather, store, and use information about their collections (collection information). Our objective was to assess how well each museum was doing this in order to account for objects in its care (as part of its permanent collection, on long-term loan, in its custody, borrowed, or on loan) and to support its wider activities such as research, exhibitions, education, and other public programmes.1

5.2

We summarise our key findings, and raise issues for consideration, from our assessment of:

- why museums need a collection information system;

- what a collection information system should contain;

- the use of registration documentation to account for collection objects;

- the administration of loans to and from museums;

- ways to gather and store collection information;

- access to and use of collection information systems;

- retrospective documentation to improve collection information;

- the use of collection inventories; and

- converting collection information into a digital format.

Key findings

5.3

The system for recording information about objects a museum holds in its collection fulfils vital accountability and management functions. A collection information system enables the museum to not only account for what it holds, but also to interpret collections in their social and historical context by delivering a variety of services to its community and the wider public. With a thorough knowledge of its holdings and their significance, a museum is better able to draw up an active strategy to develop its collection, build on the collection’s strengths, and take steps to strategically add to its holdings.

5.4

The museums we audited were using the necessary administrative documentation to record and account for their permanent collections through the processes of registration and cataloguing. However, some had substantial undocumented holdings.

5.5

Museums frequently lend or borrow objects that can be of considerable artistic, cultural, or financial value. This movement of objects between museums imposes important accountability obligations on the lending and borrowing institutions. Loan documentation was generally comprehensive, and museums were keeping appropriate records of objects on inwards or outwards loan. In the few cases where practices were inappropriate or needed to be improved, we raised those matters with the museums concerned.

5.6

For a variety of historical and other reasons, some collection records were incomplete or unreliable, and information about objects needed to be consolidated and verified. As a consequence, most museums were facing a backlog of cataloguing work to build up a body of complete and accurate object information for some parts of their collections. Although most museums have work under way to address this backlog, only limited progress is being made. Many museums are likely to face years of work to complete the task. It involves describing possibly tens of thousands of objects, including information about their origin and significance.

5.7

Museums were recording collection information in electronic databases, or were intending to do so. However, most were not using the databases for the full range of museum applications, and lacked the staff – and sometimes the necessary museum processes – to make better use of electronic tools. This was limiting the potential for more effective management of their collections through access to information about object-related activities. Only one museum had a comprehensive plan setting out how it would use documentation for managing and developing its collection.

5.8

Electronic databases offer significant capability to integrate object data and search through the collection. However, a significant number of museums had no manual to standardise documentation procedures. Our checks of museum documentation identified some errors in data. This highlights the importance of accurate and consistent data entry and maintenance.

5.9

The quality of collection information generally is variable. Incomplete or incorrect data undermine confidence in the information system and make searching and retrieval unreliable.

5.10

Museums were setting up useful initiatives to make their collections more accessible to the public, including providing electronic information about collections.

5.11

Most museums had carried out inventories of parts of their collections. However, with limited staff resources, they were often making slow progress, and work to follow up on identified problems was unfinished. Museums had not drawn up a systematic programme of collection inventories to provide ongoing oversight of the collection and associated records.

5.12

Most museums had programmes to create digital images of objects in their collections. However, few had a plan for their digitisation projects, and the different approach each was taking lacked the necessary consideration of objectives, resources, quality specifications, priorities, and timetables.

Issues for consideration

5.13

Museums recognise the benefits from improving the quality of information about their collections to provide a comprehensive and reliable resource for staff and the public. However, tackling the backlog of fully documenting their collections is time-consuming. In our view, museums lack the necessary staff to make significant short-term progress.

5.14

With more staff, museums would be able to make better use of their electronic collection databases. Building up a comprehensive body of accurate object information that was available electronically would give users greater confidence in the reliability of collection information. There is also scope to link processes within the museum – such as exhibition design, curatorial research, condition reporting, and loan documentation – to make electronic databases a more valuable management tool for consolidating object-related information.

5.15

Improvements to the quality of collection information also need to be supported by standard procedures for data entry and maintenance, through documentation manuals.

5.16

Inventories are an important component of sound collection management. Priority should be given to carrying out periodic inventories. These should follow a cycle appropriate to the nature of the collection and the resources available, and establish action plans to follow up on the results. Many museums will need additional staff to carry out this work.

5.17

Many museums are facing significant work to create full catalogue records of their collections, but they are making limited progress. We identified 2 obstacles – insufficient staff to assign to the task, and the lack of strategic project plans with realistic targets and timetables. More than half the museums we audited use volunteers or other temporary staff for this work. While these people make a valuable contribution to the work of museums, we consider that some museums need more permanent staff to make measurable and consistent progress.

5.18

Effective and efficient digitisation demands careful planning to ensure the quality and suitability of images for different purposes, with a defined scope, specific standards for image quality, assigned resources, and a realistic timetable.

Why museums need a collection information system

5.19

Museums record information about objects so they can interpret the significance of their collections and account for what they hold.

5.20

A collection information system containing accurate, relevant, and comprehensive information about a collection serves 4 broad purposes. It:

- enables the museum to account for objects in its care;

- defines the significance of the object in the collection;

- provides a resource for museum staff and the public; and

- enables the museum to make the best use of what it holds, and establish a framework for developing the collection.

5.21

A museum must know at any time what objects it is legally responsible for (permanent collections and inwards or outwards loans). Object records define the legal status of objects in the museum’s ownership or custody, tell the museum where to find an object, and record transactions or activities involving the object (such as conservation treatment or display).

5.22

In the event of loss of, or damage to, the collection, the collection information system also provides an authoritative record of what the museum holds.

5.23

A museum also records a range of descriptive information about each object to define its place in the collection: its provenance, condition, history, and other related details. Associating objects with their histories or “stories” through this information enables the museum to authenticate objects and define their significance in the collection.

5.24

All museum activities draw on information about the collection: exhibitions, research, and educational programmes. Museum staff use this information to plan exhibitions, find suitable objects to make up displays and compile catalogues, arrange education programmes, and answer enquiries from the public, students, or researchers. It is through the museum’s collection information system that it provides public access to its collections – by indexes, by references, or on the Internet.

5.25

In addition, comprehensive and reliable information about what it holds enables the museum to exploit its collection to the full, and serves as a framework for managing and developing that collection through planned acquisitions and rationalisation.

What a museum’s collection information system should contain

5.26

National Services Te Paerangi has prepared a list of typical collection management activities or functions to be incorporated in a collection information system (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Typical activities or functions to include in a collection information system

| Database/item entry | Item name, description, ownership, provenance, history, research details, images |

| Acquisition | Date acquired, acquisition method, report, source, cost, transfer of title, accession details |

| Location and movement | Collection locations, item’s current location, item’s previous location, movement history, items in specified location |

| Conservation management | Examinations, condition report, treatment, conservation history, cost |

| Licences and rights | Copyright ownership, permission requests, licences granted |

| Insurance and valuation | Valuations, insurance details, risk management |

| Loans | Loans in, loans out, loan number, location, date, period, agreements, overdue |

| De-accession and disposal | Reason for de-accessioning, method of disposal, approval, date |

| Multimedia capabilities | Imaging, video, audio |

| Public access | Physically on site, through website |

| Data management | Data entry standards, vocabulary control, searching, indexing, thesaurus, bilingual capacity (including Māori language) and classification systems |

Use of documentation plans

5.27

The challenge for any museum is to integrate, or create relationships between, object-related information that is in different formats and has been prepared in different parts of the museum for different purposes and functions.

5.28

A documentation plan can provide a valuable framework for defining how the museum will address its documentation needs in an integrated way. This ensures that efforts to expand and improve object records are closely aligned with collection management objectives. This plan should:

- specify what the documentation system is designed to achieve;

- describe existing documentation procedures (who is responsible for what activity, for what purpose, and what records are created);

- analyse documentation flows and procedures against the aims and objectives of the museum’s documentation system to identify gaps and duplication of effort, and assess how easily records can be used and information cross-referenced and retrieved; and

- determine what staff, equipment (such as computers, cameras, or scanners), or facilities are needed to address any needs arising from this analysis, how long this project will take, and what resources will be needed.

5.29

A documentation plan should also serve as a framework for managing, and for developing, a museum’s collection. It should also set out actions, including the timetable, for dealing with any documentation backlogs. A guide to writing a documentation plan is outlined on the website of the Museum Documentation Association.2

5.30

Only one museum that we audited had such a documentation plan. The plan encompassed all aspects of collection development and care, and set out clearly the purpose and functions of documentation activities and of different records. It explained how the museum intended to use object information to improve preservation, aid understanding and interpretation, improve accountability, and promote access and use.

Use of registration documentation to account for collection objects

5.31

Museums account for what they acquire and hold, and the status of objects in their collections, through descriptive information known as registration documentation.

5.32

Registration documentation records the legal status of an object within the museum or on loan, that object’s movement, and its care by the museum. Good registration records will provide clear evidence of legal ownership or possession, identification of objects by a unique number that allows object information and physical location to be easily retrieved, history of ownership, and status (for example, on loan, in storage, on display, or under treatment).

5.33

Documentation for the registration function should commonly include:

- Object entry documentation, for recording and monitoring new objects entering the museum until they are formally accepted into the collection (through accessioning) or returned. This documentation commonly consists of a temporary custody receipt, recording that the object is in the custody of the museum.

- An accessions register, which records all objects formally accepted into the custody of the museum, assigns a unique and permanent identification number to the object, and may contain some descriptive information about the object.

- A certificate of title that records the legal transfer of ownership to the museum from the donor, seller, or other source. In other circumstances, the ownership of objects may be defined by a loan agreement, trust deed, or other document.

- An index of donors that provides a record of members of the community who have given objects or art works to the institution.

- Records that show the location and movement of objects in the museum’s collection, or of objects on loan or borrowed.3

Completeness and reliability of registration documentation

5.34

Museums were using registration documentation to account for what they held in their collections, although some past records were incomplete or unreliable. All museums were using documentation to support accessioning and cataloguing tasks, although not all recorded the full range of information about object status. This documentation included object receipts, donor agreements and indexes, certificates of title, condition reports, and loan agreements.

5.35

Object receipts and other legal agreements with the donor or vendor should clearly record the legal conditions associated with the transaction. A good example of one such agreement was the form used by one art gallery to record the acceptance of gifts or bequests. The form records the transfer of title to the art gallery, and the art gallery’s associated obligations and rights to care for, preserve, display, store, reproduce, and lend the object. It also records the art gallery’s commitment to acknowledging the gift, and recognises the obligation to offer the work back to the donor should the art gallery seek to dispose of it.

5.36

All museums maintained an accession register that recorded the formal acceptance of an object into the permanent collection and allocated it a unique number. Objects were labelled to match the object to the associated accession documentation.

5.37

All museums acknowledged that some past records were neither complete nor reliable. This reflects the collecting and cataloguing practices at the time, and, for some objects, the absence of contextual information about provenance. All museums were improving the quality of their collection information.

Administration of loans to and from museums

5.38

Museums often lend or borrow objects, and must be able to account for all objects on inwards or outwards loan. Museum exhibitions most commonly draw on objects or art works from their own collections, but will also use selected items borrowed from others. Museums are responsible for caring properly for any objects they borrow.

5.39

Nearly all the museums we audited were involved in lending or borrowing objects, and many were displaying borrowed items at the time of our visit.

Value of objects on loan

5.40

Objects on loan may be very valuable in artistic, cultural, and financial terms. The institutions most likely to have active lending programmes are the larger art galleries. At the time of our audit, one art gallery had recently borrowed a group of art works from another public art gallery. This group of art works had a total insured value of more than $3 million.

5.41

Art galleries may also, on occasion, borrow highly valuable art works of international note from overseas institutions for special exhibitions.

5.42

The objects or art works borrowed by smaller museums or art galleries may also have a high artistic, cultural, and financial value. Two exhibitions in one district art gallery – one a display of quilts from overseas and another showing art works by various artists – had insured values of about $450,000 and $350,000 respectively.

5.43

Some collections also hold objects borrowed on long-term loan, such as Māori artefacts or art work collections. Long-term loan agreements may impose specific conditions on the objects’ use and care while in the custody of the museum. These conditions cover matters such as storage, display, or reproduction. Careful recording and filing of such agreements is vital so that the museum can properly account for its obligations as custodian.

5.44

In each museum, we examined the documentation associated with objects borrowed or on loan.

Loan documentation and monitoring of objects on loan

5.45

The loan documentation we examined was comprehensive, and museums were monitoring the status of objects on loan. The documentation included necessary details about the period of the loan, care, insurance, copyright, security, environmental conditions, transport, and handling. Museums had adequate control over inwards and outwards loans. In Part 6 we discuss in more detail the process for administering loans, in particular, the responsible care of objects on loan or borrowed.

5.46

Museum systems for monitoring objects on loan were mostly paper-based, although some were using, or planning to use, electronic databases for this purpose. This should make loan administration simpler and more systematic.

5.47

Loan documentation should be drawn up for the display of art works in community exhibition facilities. Some art galleries may provide a community venue for local artists to display their art works. Three such venues did not prepare documentation for such exhibitions, leaving them exposed to possible liability in the event of any dispute. One museum that ran an adjoining art gallery acknowledged the difficulties of determining responsibility for damage to art works put on display there with no loan agreement in place with local artists. This had led, on one occasion, to the museum having to accept insurance liability when it was unable to demonstrate proper care of a local art work damaged while on display.

Proper care of objects on loan

5.48

Museums or art galleries should not lend objects unless they can be confident that they will be properly cared for. Three museums or art galleries were lending art works to be displayed in their local authorities’ council offices. Concerns were expressed about the risks associated with this practice. The director of one art gallery that had abandoned the practice told us of paintings being damaged or lost as a result of this practice.

5.49

We share the concerns about this practice, which was inconsistent with collection policies and the collection care procedures followed by the 3 institutions.

5.50

All 3 institutions defined in their collection policies the purposes for which they would permit art works to be lent. Display in council administration areas, or in the offices of councillors or council managers, did not meet those criteria.

5.51

This practice also put the art works at risk of damage, which was a concern expressed to us by museum staff. Those concerns had led the conservator at one art gallery to recommend basic precautions to be followed for the care of paintings lent to the council for display in its buildings and offices.

5.52

However, such precautions cannot provide substantive assurance that paintings will be properly cared for and the necessary security measures followed. This was especially the case in public areas, but also in the offices of elected members or council staff. Nor did the environmental conditions meet the art gallery’s requirements. Wherever we found this practice, we recommended that it cease.

Ways to gather and store information about collections

5.53

Historically, information about collections has been recorded in a variety of paper-based systems. These are often spread throughout the museum in card indexes, donor lists, accession registers, curators’ notes, and exhibition material. Museums, therefore, worked from a number of information systems, which often made it difficult to assemble a complete body of information about an object, its history, and its use.

5.54

The advent of database software – and in particular the creation of electronic systems designed specifically for museum use – provides museums with the opportunity to manage their collections and collection-related activities in an integrated manner.

5.55

We examined the collection information system used by each museum, how it was used, and whether it was meeting the needs of the institution. We also met a major supplier of collections management software for museums to discuss the use of electronic databases.

Use of electronic records

5.56

Electronic records offer significant benefits for gathering and storing collection information. Museum staff process a variety of object-related information, such as donor files, reference files, curators’ notes, catalogue indexes, exhibition catalogues, receipts, accession registers, loan agreements, media articles, donor cards, and condition reports.

5.57

In their original format, these records met specific purposes. They tended to be created and maintained in different formats and sometimes in different parts of the museum, leading to the fragmentation of information about any given single object. This often results in a situation where there is no central, single point of access to comprehensive information about an object and its history in the museum.

5.58

In a museum, electronic databases offer significant benefits over paper-based systems because they provide:

- the ability to efficiently link and consolidate information in different media or formats, regardless of where the information may have been created or maintained in the museum. (In practice, this involves the capability to import, export, and link records – such as condition reports, treatment records, loan agreements, images, and exhibition catalogues);

- shared access and use by museum staff for searching and retrieving specific information, and for reporting;

- the ability to provide templates for key forms, field formats, and a thesaurus,4 standardising the way records are prepared by different staff and over time;

- the capacity to use data entry sequences and authorities to control and enforce mandated procedures in accordance with museum policies – for example, to ensure that all accessioning tasks are completed in sequence;

- staff with the capability to update information more readily and efficiently – for example, to record changes in the status of an object, such as when it is lent or put on display;

- better security of information than manual records (providing there is appropriate back-up);

- the capacity to be adapted to provide public access to the collection (for example, through the use of kiosks or by publication online); and

- the ability to configure the information system to meet changing needs for reporting or data gathering.

Transferring records from paper systems to electronic databases

5.59

Museums are transferring collection records from paper systems to electronic databases. All the museums we audited were using electronic collection databases, or were intending to use them, to gather and hold information about their collections.

5.60

The electronic collection databases that we saw had the capability to integrate information about objects or art works, providing a comprehensive overview of object status and condition. Through embedded templates, authorities, and field descriptions, they also impose important disciplines on collection management activities. One art gallery, for example, used a diary system within its database to schedule tasks such as condition reporting and photography of new accessions.

5.61

Purpose-designed software is likely to contain useful templates for drawing up museum documentation, such as loan agreements or condition reports. It will probably have a built-in thesaurus for object description and classification. This promotes consistent data entry and assists searching. When museums consider what electronic system will best meet their requirements, the benefits of such features need to be balanced against factors such as cost, training needs, and complexity.

Making full use of the capability of electronic databases

5.62

Museums generally have yet to make full use of the capability of electronic databases to manage their collections. Electronic systems are increasingly being used to gather, store, and retrieve information about the collection. However, in most museums much of this capability is, as yet, unused. As a result, most museums continue to use some paper-based systems alongside their electronic collection database. Some were making more use of their electronic systems than others.

5.63

In particular, electronic collection databases offer the means to centrally handle information about object-related activities in one application, including accessioning, exhibition history, loans, condition reporting, control of movements, and location.

5.64

None of the electronic collection databases we examined held comprehensive object-related information. Loan documentation, condition reports, and exhibition materials were most commonly held in separate paper files.

5.65

Nor were museums routinely establishing electronic links to this documentation. Most commonly missing from electronic collection databases – either as stand-alone fields or linked documents – were curators’ notes, exhibition records, and other research information. Registry staff in one art gallery told us that, without these links, they constantly had to manually cross-reference exhibition records to the central electronic collection database.

5.66

Along with the ability to search information about the entire collection, a major benefit of any electronic collection database lies in the ability it gives staff to link related information about an object. This facility offers benefits of carrying out relational searches, retrieving and linking associated information, monitoring the condition of objects over time, controlling and documenting location and movement, monitoring the status of loans, and undertaking a variety of other collection-related activities.

Transferring data to electronic format

5.67

The task of transferring collection information to an electronic collection database and verifying that data demands a significant amount of staff time. The task is often being undertaken by temporary staff or volunteers, or alongside competing priorities for permanent museum staff.

5.68

Barriers to the purchase of museum-specific software, or to the better use of such software, are cost (for example, to purchase additional user licences) and limited staff time to enter, maintain, and update data.

5.69

Limited staff resources to enter data – and deal with other aspects of museum administration – were particularly severe in some small museums we visited. Some museums had made more progress than others in upgrading the quality of their information management.

5.70

If significant progress is to be made in the short term, more staff will be needed to tackle this work in a systematic and intensive manner. At the time of our visit, one art gallery had begun a project to check and standardise its electronic collection database, bringing together object-related information into object files. The project was expected to take 2 to 4 years, given the competing demands on the time of registry staff.

5.71

More staff for data entry and cataloguing, and better integration of object-related processes throughout the museum – for example, exhibition design, curatorial research, condition reporting, and loan documentation – will enhance the use of electronic databases for a variety of management activities. Electronic access to object information also creates opportunities for museums to make their collections available to the public online, either through kiosks at access terminals or through the Internet.

Achieving consistent data entry

5.72

The use of electronic collection databases highlights the importance of consistent data entry procedures. Many different museum staff create and record information about the collection for different purposes. For example, curators plan exhibitions, conservators or registrars prepare condition reports, and registrars or collections managers accession objects, administer the database, and prepare loan and exhibition documentation.

5.73

In most museums, temporary staff or volunteers also carry out a variety of collection management tasks with object records. It is unlikely that information will be recorded consistently unless clear procedures are followed.

5.74

Delivering the benefits of an electronic collection database to the various users relies on the museum having data that is accurate and comprehensive.

Documentation procedure manuals

5.75

A documentation procedure manual contains instructions to standardise the recording of information about the collection, and has major benefits, including:

- ensuring continuity of practice and standardisation of procedure in all parts of the museum;

- providing clear guidance to staff; and

- providing a permanent record of the documentation system.

5.76

All museums should have a manual that provides staff with step-by-step guidance on exactly how to use the information system, how to enter data, and how to obtain information when needed. Among the activities demanding consistent recording are accessioning, location and movement control, loans, and condition reporting. With strict procedures for data entry in place and followed, users can have confidence in the accuracy and completeness of information held in the electronic collection database, and make best use of that information in their everyday work.

5.77

We asked each museum whether it had a documentation or data entry manual.

5.78

Many museums had no manual to standardise documentation procedures. Only 6 of the 13 museums had such a manual. While museum database software may be specified to provide some guidance on data entry conventions and nomenclature, manuals are important because they reflect and recognise both the processes of the individual museum and the composition of the particular collection. Manuals are also important for standardisation, and to reduce the risks of differing practices as staff change.

Effects of poor quality data entry

5.79

Object data should be entered into the collection information system in a format that enables users to readily search for the information they need. Our tests of object documentation and discussions with museum staff made us aware of the effect of data errors on the utility of the information system. These errors had come about through the failure to follow established data entry practices, or from changes in such practices over time, and included:

- the interchangeable use of database fields;

- the use of inconsistent terminology for object description; and

- the use of multiple object numbers for accessioning or cataloguing.

5.80

All such errors reduce the confidence of users in the information system and make searching and retrieval more difficult.

5.81

The effect of poor quality data was also highlighted when we carried out checks of sample records (see paragraph 5.87).

Access to, and use of, collection information systems

5.82

The main benefit of computerised collection records is the ability to search for specific information. In examining how documentation was prepared and used in each museum, we assessed whether collection information met the various needs of museum staff, and the public.

Access to, and use of, collection information by staff

5.83

Collection information is used by 2 main groups of museum staff:

- registrars or collection managers – who gather, store, and maintain descriptive information about objects, their location, and condition; and

- curators – who need access to information about the collection to plan exhibitions and answer queries from the public.

5.84

We assessed how well these information needs were met by:

- testing, for a small sample of objects in each museum, the accuracy of object descriptions, accession numbers, and locations recorded in the collection database; and

- asking curators how they use the collection information system.

5.85

Electronic collection databases will become a more valuable reference tool as the quality of information and access is improved. In most museums, some or all of the object records were stored on an electronic collection database, and curators told us that they used these databases.

5.86

However, museum staff did not rely fully on this source to obtain information about the collection. Sometimes they referred to the museum’s card indexes, used their own personal knowledge of the collection built up over time, or made a physical search through the storage areas. As more collection records are entered into electronic databases, that information becomes more relevant and reliable, and wider computer access is provided for museum staff, we would expect these electronic records to serve, more often, as the primary reference source for curators in their everyday work.

5.87

In most museums, we verified the location of a small sample of objects using the collection records. However, our checks also revealed some instances of deficiencies in the quality of those records, including:

- missing descriptive details;

- object records that did not always show the correct physical location;

- errors in data entry, confirming the importance of following consistent and well-defined data entry procedures; and

- inconsistent object descriptions or nomenclature, sometimes making initial searches unsuccessful.

5.88

In one museum, some objects had no identifying number, or were not recorded in the card index, making it necessary to carry out a physical search of the collection area to locate them. Reliable paper records are critical to creating a useable electronic database, and our audit confirmed the need for the museum to verify its paper records before transferring them to an electronic system.

Improving public access to, and use of, collection information

5.89

The other main user of collection information is the public. Many museums have only a small proportion of their collections on display. That figure is as low as 0.5% for one large museum. Making the rest of their collections accessible is an important task.

5.90

Museums were actively exploring ways to make their collections more accessible to the public. This included publishing information in an understandable format.

5.91

Improving the quality of collection information systems will help to provide better public access to collections, by providing reliable and comprehensive records of a museum’s holdings and digital images to complement the object description.

5.92

Five museums, including the 2 large art galleries, offered the opportunity for the public to view images of their collections online. Other ways in which access is provided include tours of the museum, libraries, and kiosks for searching the electronic collection database.

5.93

An important part of most museum collections is their large, valuable archives of material about the history of their regions. Of particular interest to students, historians, and researchers, this material includes community records, local newspapers, maps, and photographs. The public has supervised access to this material.

5.94

Public access was well organised and supervised at the museums we visited, with a variety of finding aids in paper or electronic format. This included indexes, microfilm readers, catalogues, booklets, and data sheets. The services provided by museums through these public research centres were well used and valued.

Use of retrospective documentation to improve the quality of collection information

5.95

The term “retrospective documentation” refers to the process of tackling backlogs or gaps in basic documentation to ensure that a museum knows the identity and location of all items for which it is responsible. Retrospective documentation also involves continually improving incomplete, inadequate, and inaccurate documentation and producing new information about collections.

5.96

All the museums we audited recognised the need to improve the quality of information about their collections. We asked them about their problems with collection information, and how those had come about.

Status of collection information

5.97

The museums we visited faced common problems with the completeness and accuracy of their records:

- Knowledge about what was held in the collection was sometimes poor. Some museums had inventories under way in parts of the collection to provide this base information. However, in others, no resources are available to do this work. We discuss the importance of collection inventories in paragraphs 5.112-5.125.

- Successive curators and museum directors may introduce new practices in registration, numbering, and description that make it difficult to identify and trace objects. Changes in the way objects are accessioned and catalogued make it difficult to catalogue and link different object information sources (such as donor indexes, accession registers, object labels, and loan agreements). In some instances, this has left museums struggling to work from information held in different (and sometimes conflicting) documentation systems.

5.98

In many museums, past collecting and recording practices had created a situation where information about objects was fragmented or held in different parts of the organisation. Information was sometimes incomplete, poorly linked, and unreliable. This means that present-day staff must refer to different information systems to carry out core tasks such as retrieving object details, locating an object, or monitoring loans.

Benefits from improving collection information

5.99

Improving the quality of collection information has a number of benefits for museums, including:

- improving the ability of curators and other museum staff to enter and retrieve information;

- improving information about the collection and making it more accessible to the public – for example, by using it to plan fresh exhibitions;

- being able to review the collection against the purpose of the museum and its collection policies; and

- more systematic monitoring of object status and condition.

5.100

We saw evidence of the benefits of improving collection information – for example, cataloguing and re-housing a social history collection in one museum, proofreading object data in another, and indexing archives to create findings aids for the public in a third.

5.101

Good collection documentation also makes the work of museum staff much easier. Our checks of sample collection records confirmed the importance of accurate and comprehensive records to support the everyday work of curators and registry staff.

Progress in dealing with retrospective documentation

5.102

We asked what museums were doing to improve their collection information.

5.103

Retrospective documentation is recognised as a priority by museums. However, limited progress was being made. We identified 2 related factors as the primary barriers to museums significantly reducing their cataloguing backlog – a lack of dedicated staff and a lack of project management.

5.104

To address cataloguing backlogs, museums rely on the limited time available to permanent staff after carrying out their main work, temporary staff engaged with short-term project funding (where short-term funding is available), or volunteers. These resources do not provide the dedicated effort needed to make significant progress. For example, when one museum assessed its progress in reducing its cataloguing backlog, it concluded that the task would take several years. Other museums also face years of work to complete documentation of their collections.

5.105

Museums Aotearoa’s strategy for the museum sector notes –

Much of the work of documenting our nation’s heritage has been chronically under-resourced. Many institutions within the sector have not had the resources to maintain a consistent approach to documentation.

The work in some major museum institutions to record their collections given the present level of resourcing available is likely still to take several years.

5.106

Our findings confirm this view. An increase in permanent staff is needed if significant results are to be obtained within a reasonable time.

Strategies for improving retrospective documentation

5.107

In our view, museums need to take a disciplined, project-based approach to dealing with cataloguing backlogs. While all museums were facing a backlog of cataloguing work, only 3 had set strategic priorities and adopted a supporting planning framework to tackle the task in a systematic way.

5.108

Allocation of additional funding, or the reallocation of existing resources, should be subject to approval of a well-argued business case, based on a project plan. A properly prepared plan that includes costs would provide an important discipline for museums, and help to ensure that there is accountability for outcomes. It should define the scope of the work, estimate the resources required, set out the data standards to be met, and set realistic timetables for completion.

5.109

There are difficulties in estimating the effort required for different parts of the collection or for specific objects. For example, one donation may include a large number of objects, all of which need to be individually described, labelled, and housed. Furthermore, some cataloguing work is more time-consuming than others. In most museums, some objects or collections are well documented, while minimal documentation is available for others.

5.110

These factors, and the lack of dedicated staff, make project planning difficult. However, without a considered approach to this time-consuming work, competing priorities for staff and the scale of the work needed will make it difficult to achieve results, targets are unlikely to be realistic, and completion of this task will continue to be deferred.

5.111

The challenges faced by one museum to improve the quality of its collection documentation are typical. However, the museum’s strategic and disciplined approach to addressing those issues has given it a strong framework for making measurable progress. This is illustrated in Figure 8, which describes the approach taken to address the museum’s cataloguing backlog.

Figure 8

One museum’s approach to addressing a cataloguing backlog

| The museum faces a significant backlog in cataloguing work and other tasks to make its collection information more accurate and comprehensive. Limited information is held for some objects, and, in the past, different numbering systems were used for different collections. Some accession registers contained limited information. Object information was recorded in different formats and with different indexes, held in different folders, and included deposit records, accessions sheets, and donor receipts. For any cataloguing task, object information needed to be retrieved from different sources. We examined how the museum was tackling the task of assembling and rationalising this information. The museum has taken a systematic approach to assessing the extent of this work. This began with an analysis of the nature and extent of the task, and of the obstacles to dealing with the backlog. The museum identified the shortcomings with documentation of the museum’s collection, and noted that many objects had not been recorded in the electronic collection database. It also changed the division of workload among its collections staff to free up resources for this work. In 2001, the museum analysed in detail the resources needed to eliminate the backlog of registration and cataloguing tasks. The plan provided a rational outline of work required (such as verifying object descriptions, checking locations, and entering and checking data) and likely timetable for it to be completed. An inventory of the collection has been important in identifying outstanding cataloguing work. This process has involved reconciling location and object details to the database record, and filling out object descriptions. Associated work includes preparing object lists and linking object records to information sources held in other software applications (such as text documents), databases, or paper records. A museum report of September 2004 summarised the results of the inventory to date. The museum has used this data to define project outlines for ongoing collection management work and specify project objectives, staff assigned, tasks, output targets, and timelines. The museum has imposed a moratorium on all new acquisitions so as to tackle its backlog. Project plans – such as that for recording, updating, and verifying object data – are also translated into specific, time-bound objectives for staff. |

Use of collection inventories

5.112

We asked whether museums had carried out inventories5 of their collections, the results, and follow-up action.

5.113

Most museums had carried out inventories, but generally only of parts of their collections. Some were carrying out inventories at the time of our audit.

5.114

Collection inventories serve a number of important accountability and management functions:

- They are a record of what the museum holds and is responsible for in legal terms and for insurance purposes.

- They verify object documentation, such as location descriptions and consistency between accession numbers and objects. The results of an inventory will tell the museum about the quality of collection information, and identify areas where further work is needed. In addition, an inventory provides an opportunity to enhance object records – for example, by adding digital images to descriptive information in the collection database.

- They provide a means of monitoring the condition of objects and determining conservation needs, including future storage requirements.

- They provide the basis for a review of the relevance and significance of the collection to inform collection development, and identify objects or collection groups for possible de-accessioning.

Planning and conduct of collection inventories

5.115

To produce meaningful results, collection inventories need to be well planned and systematically conducted. A well-planned inventory will produce meaningful results on which action can be taken.

5.116

On moving to a new building, one art gallery had carried out a full inventory of its collection, using codes to classify problems found in the course of the work. These codes enabled registry staff to analyse the results in a systematic way, and to group issues into categories for follow-up action. The codes were for:

- condition;

- location;

- numbering;

- storage; and

- documentation.

5.117

Figure 9 shows the format for the data collection sheet used by the art gallery’s registry staff to carry out the inventory, with illustrative entries to show how results are compiled for analysis and follow-up action.

Figure 9

Example of a data collection inventory sheet*

| Location | Code | Problem | Suggested action | Action taken | Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Box 16 – BAY 8 | SQ | Contents list incorrect | Print new listing | - | - |

| Box 17 | NL | Current location listed as Box 14 – BAY 9B | Initiate search | Located in Box 14 – BAY 9B | 15/3/05 |

| Box 18 | WL | Found, but not listed at this location | Update location record or transfer work back to correct location | - | - |

| Box 19 | CQ | Hinge detached | Refer to conservator | - | - |

| Box 20 | DQ | Works not identified individually or listed | Formal listing and numbering required | - | - |

| Box 21 – BAY 1 | IN | Labels do not match accession number | Check accession register, object data sheet | - | - |

Key: CQ – Condition Query; WL – Wrong Location; IN – Incorrect Numbering; NL – Not Located; SQ – Storage Query; DQ – Documentation Query.

* From Collection Inventory 2005 – Art Works on Paper.

5.118

Our analysis of the inventory results showed that most of the problems identified related to the accuracy of documentation, with some mismatches between object labels and database records.

5.119

Inventories should be well planned, with a view to the information to be gathered and analysed. Poor planning and record-keeping will directly affect any benefits from an inventory. We were told at one museum that the former director had conducted a full inventory of the collection, but had left behind few written records and no report. The museum was again beginning an inventory of parts of the collection to build up the museum’s knowledge of its collection.

5.120

Ideally, every museum should have a forward schedule of inventories, enabling it to verify what it holds, check the accuracy of object records, monitor progress with ongoing collection work, and review its collecting plans. Only one of the museums we visited – one of the larger art galleries – had a programme for scheduling inventories of its collection.

5.121

The art gallery had a clear policy, objectives, and procedures for its inventory programme. Different approaches had been considered, with an estimate of the associated resource requirements. The art gallery has a 2-yearly inventory cycle for each of its permanent locations. In addition, having regard to significance and risk, a 6-monthly stocktake is undertaken of high-value art works and of art works on long-term loan. Worksheets are used to record the results of inventory checks by codes, enabling easy analysis and follow up.

5.122

Because of the size of their collections, museums, in particular, face a challenging task to carry out inventories of their collections, and may need to schedule this over several years.

Assigning priority to periodic collection inventories

5.123

As a result of limited staff numbers and competing tasks, museums are not assigning the necessary priority to periodic inventories of their collections. However, in some cases, inventories had been in progress for months or even years, with competing work priorities limiting progress. This was particularly the case where museums relied on temporary staff to carry out this task, or where it was being undertaken by curators along with other competing responsibilities.

5.124

The experience of one museum illustrates the difficulties of assigning adequate resources to inventories. In that museum, an inventory of part of the collection had been started in 1998 when a contractor was employed for 12 months to assist with the job. In late 2001, the museum engaged temporary staff to continue the job. However, at the time of our audit, significant parts of the inventory and associated documentation were yet to be completed. This was expected to take another 2 years.

5.125

Problems raised in inventories should be followed up promptly with appropriate action. In practice, effective and timely follow up requires additional resources, which may not be available. Our analysis of inventory results in one museum showed that much follow-up work remained outstanding. In another, we were told that the recent inventory had revealed that as much as a third of the collection needed minor conservation work. This would require a major reallocation of resources.

Converting collection information into a digital format

5.126

Digital images of objects are an integral part of museum documentation. They:

- are a means of accounting for objects or art works by providing a record and visual identification in the event of loss;

- through association with descriptive records, enable users to more readily search for and identify items in the collection database;

- enhance the usefulness of condition reporting by showing the nature and location of damage;

- broaden public access to the collection (in particular for rare and fragile items) while minimising the risks associated with physical handling; and

- enable publication and reproduction.

Benefits of adopting a digital format

5.127

All museums had digitised, or were in the process of digitising, their collections. Benefits we noted included:

- visual identification to aid electronic searching;

- enabling staff to find objects more quickly by using images to mark the location of objects in storage bays;

- verification of object condition to accompany loan documentation or conservation treatment; and

- meeting growing public expectations by providing enhanced access to the collection (in particular through the Internet), and providing the facility for reproduction.

5.128

Digital images can also be used as an effective tool for planning and designing exhibitions. Time is saved because staff do not need to physically search storage areas to choose the most suitable object for an exhibition.

5.129

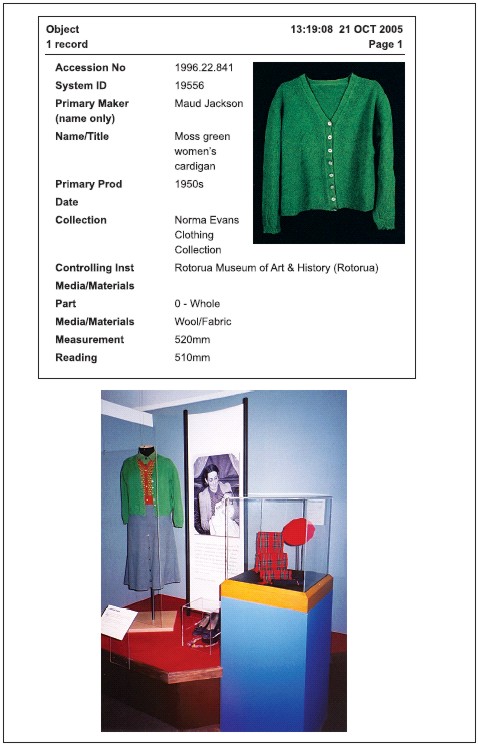

Figure 10 shows a digital image of an object, and how the object was used in an exhibition at a museum we visited. The first picture shows the museum’s object record, which includes the digital image and information about the object. The exhibitions programmer viewed the object record and selected the object as being suitable for the planned exhibition. The second picture shows how the object was displayed in the exhibition. Using digital images in the planning stage assisted the programmer to design the exhibition display to best effect.

Planning the digitisation process

5.130

We examined the way museums were going about the digitisation process. We expected each museum to have drawn up a plan outlining the objectives of the process, and to have used that plan as the basis for its programme.

5.131

Museums were approaching the task in different ways. These different approaches included taking images of all new acquisitions, of exhibitions, of objects in a selected part of the collection, or as part of an inventory.

5.132

Most approaches lacked a considered rationale. There was little evidence that careful thought had been given to the purpose, priorities, specifications, or timetable for completion. A well-thought-out plan should specify clearly:

- the objectives to be met by the digitisation programme;

- the resources needed (for example, will museum staff carry out the work or will a professional photographer be used?);

- the technical specifications for image quality (such as resolution, image dimensions, file type, and file size) as required for the defined uses and as compatible with museum software and hardware;

- image specifications, to allow for changes in technology, and ensure suitability and the maintenance of archival quality for long-term storage;

- the required equipment and facilities, including back-up and security;

- requirements for logical and efficient integration with other museum activities;

- the scope of the project (whether the entire collection or only selected objects will be digitised); and

- how images will be arranged and linked – to catalogue records, website, and other finding aids – to allow searching and browsing.

Figure 10

Using records of images to design exhibition concepts

Thanks to the Rotorua Museum of Art and History for the use of these images.

5.133

Without a clear project plan, valuable staff time may be wasted, images may not serve the various intended purposes, work may have to be duplicated in the future, and targets for completing the task may not be met. A considered approach would ensure that images meet the standards expected of users, the value of the investment is maximised, and benefits are realised within a defined time. A project plan may also help win support for the museum’s business case seeking funding for this work.

5.134

One museum had taken a particularly well-considered approach to digitising its collection with images of a publishable standard. The museum’s plan contained clear specifications, and the project was integrated into its core business. Careful consideration had been given to the purpose, use, and format for images from the collection, as well as processes for image capture, input, and storage. Timetables and resources (staff and technical) had been estimated, and the digitisation programme was designed as a workflow concept. The museum had an in-house photographer responsible for providing images for collection documentation and exhibitions.

1: Good practice in museum documentation is described in a range of texts and articles. Three examples are: The New Museum Registration Methods edited by R A Buck and J A Gilmore and published by the American Association of Museums; the MLA Accreditation Scheme for UK museums; and SPECTRUM: The UK Museum Documentation Standard.

2: See www.mda.org.uk.

3: We discuss loan documentation more fully in Part 6.

4: A thesaurus is a controlled list of standard terms that can be used to conduct word searches on a database – for example, electronic databases on the market include hierarchical structures and authorities for specific data, such as natural history collections, and authoritative references such as Chenhall’s Nomenclature.

5: An inventory may also be known as a collection survey, stocktake, or audit.

page top