Part 4: Responding to incursions

4.1

In this Part, we set out our findings about how well the Ministry is able to respond to different types of biosecurity incursions. We describe the response system then discuss our views on:

- using the biosecurity response system;

- response partners' views on biosecurity responses; and

- improving the response system.

Summary

4.2

Implemented in 2008, the new biosecurity response system (the response system) improved biosecurity response management. It provides a single approach to all different types and sizes of responses. However, it is not being used to its full potential, and Ministry staff need to better understand the response system.

4.3

During responses, there are many others who work with the Ministry. Most of these response partners told us that they believe they had a high-trust relationship with the Ministry and are supportive of closer working, but think that the Ministry needs stronger response capability.

4.4

The response to kauri dieback is an example of a successful partnership approach to a biosecurity incursion, which could provide a model for relevant future incursions. The Ministry's relationship with iwi and other agencies strengthened during the kauri dieback response and the collaboration between the Ministry and iwi was regarded by all parties as an innovation.

4.5

Measuring performance is essential to ensuring continuous improvement in public services. The Ministry needs better ways of measuring its response performance, especially how effectively and efficiently it responds.

4.6

The Ministry has a good track record of innovating and supporting innovation during biosecurity responses. Most of the examples of responses we looked at included some form of innovation.

The response system

4.7

The Ministry's 2008 response policy describes response as:

The actions taken immediately before, during or after a risk organism has been confirmed where management of the risks posed by that organism is considered appropriate. A response may be triggered where the impacts of the risk organism have increased, or new response options become available, that make a response feasible.

Response can include:

- investigation of suspect risk organisms;

- identification of the organism, containment, and initial assessments of the organism's impacts and response options;

- efforts to eradicate a risk organism;

- long-term management to mitigate the impacts of an established risk organism, sometimes referred to as "pest management".

4.8

The Ministry's response system is broadly comparable to the Co-ordinated Incident Management System for multi-agency responses to incidents. This should mean that other agencies could adapt to the biosecurity response system reasonably quickly if needed. The response system's major strength is its flexibility. It is:

- generic – it can be adapted to all types of response;

- versatile – staff learn one response system;

- scalable – it can be adapted to all sizes of response; and

- self-contained and portable – all necessary flowcharts, role and task descriptions, and tools are in the Knowledge Base, which is accessible through the Internet.

4.9

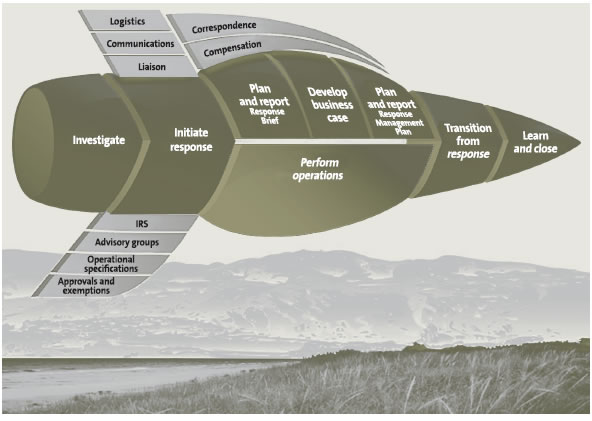

Figure 11 shows the response system's broad phases.

Figure 11

Main phases of the biosecurity response system

Source: Ministry of Primary Industries.

Using the biosecurity response system

4.10

Particular pests and/or diseases, such as foot and mouth disease, would have a particular and significant effect on the economy. However, there are many aspects of a response where it is best to have a generic approach. There is no contradiction between having a generic approach and specific plans for high-impact pests or diseases, where these plans fit within the umbrella of the generic approach.

The biosecurity response system relies on sound judgement

4.11

Implemented in 2008, the response system improved biosecurity response management. It provides a single approach to all different types and sizes of responses. Before this, different systems were used for different response types, such as plant, animal, and marine. The response system is designed to be flexible and scalable. The response system is more efficient because staff no longer have to adapt to different methods in each response. A new response policy was also introduced in 2008. Both the response system and response policy are designed to work closely together. The response system has strengthened how responses are managed.

4.12

The Knowledge Base (see paragraph 3.73) also supports the system's use in responses.

4.13

Using the response system properly depends heavily on staff judgement. The manager of a response needs to scale the response system correctly to the size of the incursion, which is difficult. Managers must choose which parts of the response system and tools are the most appropriate to use in a particular response. If they choose too few, they may not deal effectively with the response. If they choose too many, they will waste resources. Much of this kind of judgement cannot be taught; it can only be achieved through learning from direct experience. Without good judgement, the response system will not be applied as well as it could be.

4.14

Early on, the Ministry recognised that it had to improve its staff's ability to make good judgements. Because of the need for good judgement, the response system was prepared with built-in capability standards covering the principal roles and based on the Lominger competency system. The response system was designed to use an individual's day-to-day work to improve capability. The overall objective was to have a sustainable pool of capable people to lead and manage responses. To support on-the-job learning, a mentoring team provided real-time help to staff working on responses. This gave the Ministry the necessary tools to achieve its objective of a pool of capability.

4.15

The Ministry prepared and successfully introduced the response system and the Knowledge Base but failed to embed it completely. Managers – whose accountability was variable – were responsible for making the response system part of the routine approach to dealing with biosecurity incursions. Applying the capability standards and the response system consistently was reported to be challenging. There are doubts about how well the response system, the capability standards, and the Lominger competency system became routine. We did not find out how many staff completed the capability standards but we were told that few did. The mentoring team has since disbanded and the capability standards are not used. Poor implementation means that the Ministry has struggled to achieve its objective of developing a sustainable pool of capability.

4.16

Poor human resource practice has probably contributed to the lack of success in making the capability standards part of routine work. Our review of the 2010/11 BASS data shows that the Ministry failed to meet two good practice standards for human resources. They were:

- all employees have clear and measurable outcome-based targets set at least once a year; and

- all employees have a formal, recorded performance review, at least once a year, to track personal and professional development.

4.17

Applying basic human resource techniques inconsistently makes it difficult for an organisation to fulfil its objectives.

Staff need more understanding of the response system

4.18

Exercise Taurus 2012 was a good way for the new managers to check how well staff knew the response system and pinpoint any problems. An evaluation survey after the exercise showed that only 39% of respondents thought that the available tools and documents were understood well and used throughout the exercise. However, the same survey showed that 98% of respondents thought that their team was successful.

4.19

We understand from these results that teams consider that they work successfully without using the documents and tools provided, which suggests that staff do not see the need for them. If staff are not familiar with the tools and procedures, there is a risk that they will not use them nor see the need to use them.

Response partners' views on biosecurity responses

Response partners think stronger capability is needed

4.20

Many response partners who have worked with the Ministry during responses consider that its ability to respond to incursions is not as strong as it should be. Figure 12 shows that some expressed concern at what they saw as inexperience among the Ministry staff they met.

Figure 12

Views about the experience, skill, and knowledge of Ministry response staff

| Does the Ministry provide response staff with the necessary experience, skill, and knowledge to perform their role? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gum leaf skeletoniser | ||

| Didymo | ||

| Southern saltmarsh mosquito | ||

| Kauri dieback | ||

| Psa | ||

| Juvenile oyster mortality | ||

| Key | ||

Note: These views are from response partners for each of the examples we reviewed. See paragraphs 1.23 and 1.26-1.28, and Figure 3.

4.21

Response partners considered that having too few experienced staff stretched the Ministry's ability to respond effectively, mentor and train inexperienced staff, and inspire confidence among others at the same time.

Partners and the Ministry generally have a high-trust relationship

4.22

Most response partners told us that they believe they had a high-trust relationship with the Ministry. Figure 13 summarises how response partners perceived their relationship with the Ministry.

Figure 13

Views about relationships

| Does the Ministry develop high-trust relationships with response partners? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gum leaf skeletoniser | ||

| Didymo | ||

| Southern saltmarsh mosquito | ||

| Kauri dieback | ||

| Psa | ||

| Juvenile oyster mortality | ||

| Key | ||

Note: These views are from response partners for each of the examples we reviewed. See paragraphs 1.23 and 1.26-1.28, and Figure 3.

4.23

Response partners consider that working together successfully is a good way to build trust. Those who dealt with didymo describe their relationship with the Ministry as one of high trust, attributing much of this to the joint work since the response began in 2004. The Ministry's strong evidence-based approach to eradicating the southern saltmarsh mosquito helped to build trust in the Ministry's methods. These successes put the Ministry in a stronger position to work collaboratively on responses.

4.24

Many response partners see potential in, and support the idea of, a closer working relationship with the Ministry. However, the relationship with response partners needs to be bigger and more long-term than just response work. Some of the organisations we spoke to, such as local authorities, have recently signed up to the Network (see paragraphs 3.89-3.94). If successful, the Network is one way to support closer working, but it does not cover all response partners. Stronger relationships could potentially increase response effectiveness.

Response partners need better induction

4.25

Many response partners reported that, although they took part in a response, they did not understand the response system, how it worked, and what the relative roles and responsibilities were. There was no training or induction to the response system. These views were spread widely throughout the full range of response partners.

4.26

Figure 14 summarises how response partners perceived the Ministry's induction and training for the biosecurity response system.

Figure 14

Views about the provision of induction and training

| Does the Ministry provide response partners with induction and training in its biosecurity response model? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gum leaf skeletoniser | ||

| Didymo | ||

| Southern saltmarsh mosquito | ||

| Kauri dieback | ||

| Psa | ||

| Juvenile oyster mortality | ||

| Key | ||

Note: These views are from response partners for each of the examples we reviewed. See paragraphs 1.23 and 1.26-1.28, and Figure 3.

4.27

Without induction, response partners will not understand their role and the context of the whole response. There are isolated examples of response partners being familiar with the response system. However, this tends to be a secondary benefit of other work, rather than a result of a response induction. For example, partners responding to didymo are familiar with the response system because they were consulted when it was being devised.

Example of a successful partnership for working on responses

4.28

The response to kauri dieback is an example of a successful partnership approach to a biosecurity incursion and could provide a model for relevant future incursions. The collaboration between the Ministry and iwi was regarded by all parties we spoke to as an innovation. The Ministry's relationship with iwi and other agencies strengthened significantly during the response.

4.29

Kauri dieback is a microscopic fungus-like organism that affects only kauri and kills trees and seedlings of all ages. In October 2008, the Ministry started a collaborative response. This joint-agency "one-team" approach included the Department of Conservation, Auckland Regional Council, Northland Regional Council, Environment Waikato, and Bay of Plenty Regional Council. In October 2009, the response ended and the Government funded long-term management until 2014.

4.30

At first, the Ministry was slow to include Māori in the response to kauri dieback. Since 2009, the Ministry has concentrated on having an open and honest relationship. Iwi told us that they saw Ministry staff prepared to step in and work with all parties to sort out misunderstandings. For example, early in the response to kauri dieback, the Ministry recognised that Māori representatives should be compensated for their work and the time they spent preparing. This helped to create a stronger relationship with iwi.

4.31

Māori are full response partners. The kauri dieback response was the first time that the new response system had been used jointly with other agencies. Many matters had to be worked through, which, in turn, brought learning. Having agreed that there would have to be further innovations to ensure that iwi were response partners rather than stakeholders, the Ministry and iwi:

- formed the Tāngata Whenua Roopū reference group, which allows Māori viewpoints to be included in the response to kauri dieback – representing all Māori views is difficult, but this is a major innovation; and

- agreed to have iwi representatives in the most important of the kauri dieback response working groups – including having two iwi members on the Technical Advisory Group.

4.32

We consider that the response to kauri dieback has provided the Ministry with valuable experience of working in partnership and of dealing with culturally significant biosecurity incursions. If the learning from this is embedded, the Ministry should be well placed for similar responses.

Improving the response system

Measurement of response performance needs to be better

4.33

Measuring performance is essential in ensuring continuous improvement in public services. Clarifying outputs and outcomes achieved for the resources expended makes it easier to hold organisations, work groups, and people accountable. Performance measures should follow from a statement of the organisation's objectives.

4.34

The Ministry has a standalone IT system to track responses and this provides some basic information. This gives a broad indication of the number of responses at any one time, how long a response has been in operation, and what stage it is at. This is helpful for monitoring overall progress. However, we found no evidence of more robust performance measures that would show the effectiveness or efficiency of biosecurity responses.

4.35

At the start of each response, the Ministry sets out broad target outcomes. Our case studies showed that, in general, the Ministry achieved its broad target outcomes. To test the processes in place, we reviewed a further random sample of 23 responses between 2010/11 and 2011/12. Nearly all the main process documentation was present, but their completeness was variable.

4.36

Although the Ministry generally achieves its target outcomes, without systematic performance measurement the Ministry cannot show whether it could achieve its objectives in a more effective and efficient way.

| Recommendation 7 |

|---|

We recommend that the Ministry for Primary Industries prepare a suite of performance measures to:

|

Risks of inconsistent decision-making

4.37

Biosecurity's origins are in protecting primary production, vital to New Zealand's economic welfare. The 2003 biosecurity strategy highlighted that biosecurity includes protecting flora and fauna, human health, and parts of our lifestyle and national identity. Figure 15 shows how the biosecurity system should assess how much we are prepared to pay to protect these assets, using the four values framework.

Figure 15

Four values framework for assessing the effect of a biosecurity incursion

| The 2003 biosecurity strategy rejected the notion of a hierarchy of values. The economy, biodiversity, and society are interdependent, so deserve equal and consistent treatment in biosecurity decision-making. The four values framework was created to help assess the effect of biosecurity incursions on:

|

Source: Biosecurity Council (August 2003), Tiakina Aotearoa Protect New Zealand: The Biosecurity Strategy for New Zealand, Wellington.

4.38

Failure to make decisions based on a balanced and equal view of the four values can lead to inconsistent response decisions. In 2010, the great white cabbage butterfly was found in New Zealand. Overseas, this insect is a significant pest of brassica crops, such as cabbage. The butterfly could potentially affect the country's brassica industry and home gardeners and may be a significant threat to some critically endangered native brassica.

4.39

When the Ministry first assessed the risk from the great white cabbage butterfly, it considered only the risk to the economy. In November 2011, after the Ministry found that the butterfly had become established, the response team was directed to stand down. However, the Department of Conservation expressed concern at this decision, saying that the Ministry had not fully considered the butterfly's potential effects on endangered native brassica. In late 2012, the Ministry agreed a partnership with the Department to continue the response with a shared funding approach and the Department as lead agency for this response.

4.40

Inconsistent response decisions like these can confuse and frustrate staff and response partners. The Ministry's staff and response partners are strongly motivated, have a sense of mission, and believe that their work is worthwhile. If motivation is eroded, that is a risk to effective response activity.

There is a good track record of innovation during responses

4.41

The Ministry has a good track record of innovating and supporting innovation during biosecurity responses. Figure 16 summarises how response partners viewed the Ministry's attempts to innovate during responses.

Figure 16

Views about innovation by the Ministry

| Does the Ministry add long-term value to biosecurity response work through innovation and creative thinking? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gum leaf skeletoniser | ||

| Didymo | ||

| Southern saltmarsh mosquito | ||

| Kauri dieback | ||

| Psa | ||

| Juvenile oyster mortality | ||

| Key | ||

Note: These views are from response partners for each of the examples we reviewed. See paragraphs 1.23 and 1.26-1.28, and Figure 3.

4.42

We found some innovative practice and response partners reported that:

- Early ways of detecting kauri dieback were inaccurate so the response team worked out new ways to detect kauri dieback in soil. In doing so, the team detected many new organisms and the new methods could potentially be used in other incursions.

- The Psa incursion and response helped Plant and Food Research (a CRI and one of the Ministry's response partners) to understand genomics better. This led to new tools for diagnosing Psa, which should lead to better detection.

- The Ministry and Landcare Research prepared a joint operational protocol, which overcame problems in sampling kauri dieback that had introduced a contamination risk. This should improve the chances of successfully detecting kauri dieback.

4.43

To respond to the didymo incursion, the Ministry set up a research facility at Waiau River for use by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, allowing it to test how didymo grows and affects the environment under various conditions. This provided important information about the way didymo behaves. The Ministry has now included other freshwater pests in the long-term management of didymo, which is logical and efficient. The Ministry's willingness and ability to foster innovation should help it to prepare better for biosecurity incursions.

4.44

Responding to the southern saltmarsh mosquito incursion increased knowledge about this pest, including providing significant information about how the insect lives and reproduces. The Ministry experimented with various treatments, alone and in combination, to attack mosquito larvae as well as adults, to see which was the most effective.

4.45

Eradicating the southern saltmarsh mosquito was difficult. For example, the insects are tenacious and can breed in a depression the size of a horse's hoof print. A strong Technical Advisory Group14 provided advice and included members from countries where the southern saltmarsh mosquito is prevalent. The Ministry thought carefully about how to destroy the last eggs and larvae. For example, artificial flooding forced the breeding cycle. This shows that the Ministry can take on difficult technical challenges when it has to.

4.46

The Ministry and the Ministry of Health have jointly commissioned a book about eradicating southern saltmarsh mosquito, to be published around July 2013, so that the global scientific community can benefit from the information gained during the response.

4.47

The Ministry has shown that it can listen and respond. At the time of the Psa and juvenile oyster mortality responses, Government support did not include compensation to those affected by biosecurity incursions. In view of response partners' concerns, the Ministry proposed amending the Adverse Climatic Events Contingency Appropriation, which at that time covered only events such as floods and droughts. In June 2012, the Government announced new recovery support for commercial farmers and growers seriously affected by biosecurity incursions. The new Primary Sector Recovery Policy covers agriculture, horticulture, forestry, and aquaculture producers.

14: During a response, the Ministry routinely draws on external expertise and advice, including the use of Technical Advisory Groups made up of known experts in the particular organism.

page top